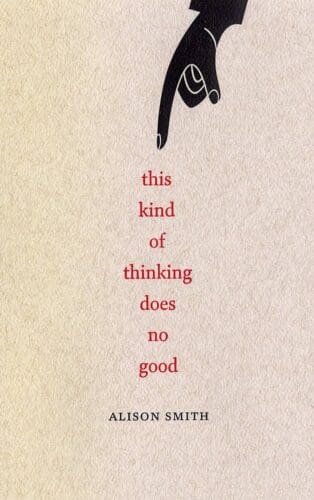

Review: This Kind of Thinking Does No Good | By Alison Smith

Gaspereau Press | 2018 | 64 Page | $18.95 | Purchase online

Gaspereau Press | 2018 | 64 Page | $18.95 | Purchase online

Review by Annick MacAskill

Cerebral, funny, and insightful, Alison Smith’s third full-length poetry collection, This Kind of Thinking Does No Good, reads as an extended response to the feminist maxim “the personal is political.” Picking up on many of the themes and tensions explored in her first book, The Wedding House (Gaspereau Press, 2001), Smith’s newest title examines the realities of women’s sexuality and labour against a backdrop of persistent sexism. Many of the poems proceed as lyric narrations on personal anecdotes, the scenes depicted ranging from childhood to adulthood. The book’s various settings are united by a speaker who, like the defiant friend in the poem “Outside the Termination of Pregnancy Room”, endures in her “refusal to find [herself] tragic.”

This speaker is deeply compelling, at once playful and direct. In “Season of Misconsent,” she references early sex education and other conventional discourses on sexuality, drawing attention to the ways they culture fear and ultimately reproduce many of the beliefs that perpetuate rape culture and suppress women’s sexual expression:

For the record, I wasn’t frigid. I started with a chest of drawers.

. In the bottom drawer, a gym teacher warning RAPE.

A sheaf of her pamphlets, or one, at the bus stop, forever

. unfolding.

Elsewhere, Smith attends to the repetitive and mundane aspects of women’s unpaid labour. In “The Poem is Your Wife,” the poet contrasts a woman’s creative ambitions with her sacrifices. Addressed in the second person to a spouse, presumably a husband, the poem opens on the wife

thinking about the right time

to ask you for a little money.

She half-mentions the years

you were in school. She waitressed,

planted trees, baked, assembled

all-weather tires, gestated children,

scoured houses. Getting older,

she listens for air-popping

enjambments and bones up

on Latin and Scientific American.

While the speaker’s tone is laconic and understated, the poet’s use of asyndeton brings attention to the uncompensated burdens of women’s work, which are difficult to leverage when they go unacknowledged. Likewise, Smith details the quotidian anxieties and efforts, both emotional and physical, of motherhood in “I Called Birth a Wonder Tale”:

. it was

easy to accuse myself

of weakness and therefore

self-improve with sharper

knives. Down with formula

and plastic! Up with grinding,

pickling, knitting, thrifting!

I advertised myself

as industrious and humble.

I looked good, but having

to prove myself, I was selfish.

Here the poet creates tension by contrasting the speaker’s wry frankness with the moralistic banalities heaped upon her.

The speaker takes a similar tone in discussing the realities of rural life in Atlantic Canada. “Come By/Come Buy” is spoken in the first-person plural, from the perspective of a women’s sewing circle that makes crafts to sell to tourists:

In the shuttered school,

tourists buy our tattered pillow slips,

cotton cloths, runners with

mauve embroidered corners.

A sum of handiwork,

something to footnote

their hardy inhalations

at the wharf, sucking in

the briny ever-was.

So-and-so at work

would not believe

how cheap the land,

oh bless […]

In these lines, Smith combines an eye for everyday detail with an understated sarcasm and direct perspicacity – the group knowingly anticipating that their “sum of handiwork” will be reduced to an anecdotal “footnote.” While this, like most of the poems in the collection, is related in the first person singular, the dominant tone is more ironic than confessional. Smith’s defiance of regionalism, sexism, and other reductive forces lies in these unforgiving, humourous, and clearly stated observations. Hers is a voice worth noting.