#NPM19: Animal, Vegetable, Mineral / Rock, Paper, Scissors: On Living Both the Urban and the Rural | By Jennifer LoveGrove

More times than I can count, this happens to me: I’m at a Toronto reading or book launch and a literary acquaintance says, “I thought you lived in the middle of nowhere in a cabin in the woods! What are you doing here?”

When I’m at the log cabin on thirteen acres of woods, field and wetlands – between Cobourg and Peterborough, not nowhere, in fact easily findable via map apps – I often hear the resident coyotes howl, and while I suppose it’s possible, I doubt they’re saying, “I thought you worked at the University of Toronto attending meetings and navigating bureaucracy, and writing your weird poems in coffee shops, biking in the rain along Bloor Street! What are you doing here?”

Bivalved

Or, having two parts hinged together. The reality is, both the writers and the coyotes are correct. I need an intensely urban lifestyle as well as a silent isolated one in order to thrive, in order to feel myself, in order to write. I’m a Gemini, the sign of the twins, two entities constantly vying for space in one consciousness, each with competing needs. We take up a lot of space. While I resist thinking in binaries or applying them to others, I do know I have two sides: one who prefers a life of interiority and solitude whose energy is generated within, and one an attention-loving extravert, buzzing on the energy of constant communication with others. Now I have found homes for each of them; one in nature, where the quiet intuition can recharge, untamed creativity and passion can flourish, the unconscious can be more easily accessed, and the other in the city, deliberate and conscious and organized, working and socializing and connecting with others, productive but always too rushed.

Unfortunately, I cannot time when one side and her needs will dominate the other, and cannot always change locations at will. Still, acknowledging this dual nature and learning how to manage it has immeasurably helped my indecisive, anxious soul. Adaptability and flexibility is what unites the duelling selves.

And, or, and, or, and. And. And.

Turtle shell

Or, home away from home away from home. As often as I can, I explore the cultural and social options available to me in this diverse city of Toronto – art, theatre, music, recreational hockey, food, friends, lovers. Literary communities. These are essential to my life and my writing. They sustain me.

But also essential to me are trees, trails, animal tracks in snow, birds at the feeders, herons by the stream, deer in the driveway, an owl in the field, an otter in the pond, the Coopers’ Hawk who swoops my head every time I venture outside. The wild winds, the wild leeks, the wild raspberries, the rocks, the ice, the thorns.

When I arrive at the cabin (or “homestead” as I like to call it, though it’s far from homesteading; there’s an espresso machine and excellent wifi), I feel distant from Toronto pressures and stresses. The textures there soothe me: the bark on the birch and maple and cherry trees, the wooden beams inside, blankets crocheted by my grandmother, warm woodstove air. These facilitate a return to myself. I can finally rest. Read. Recharge.

Feral

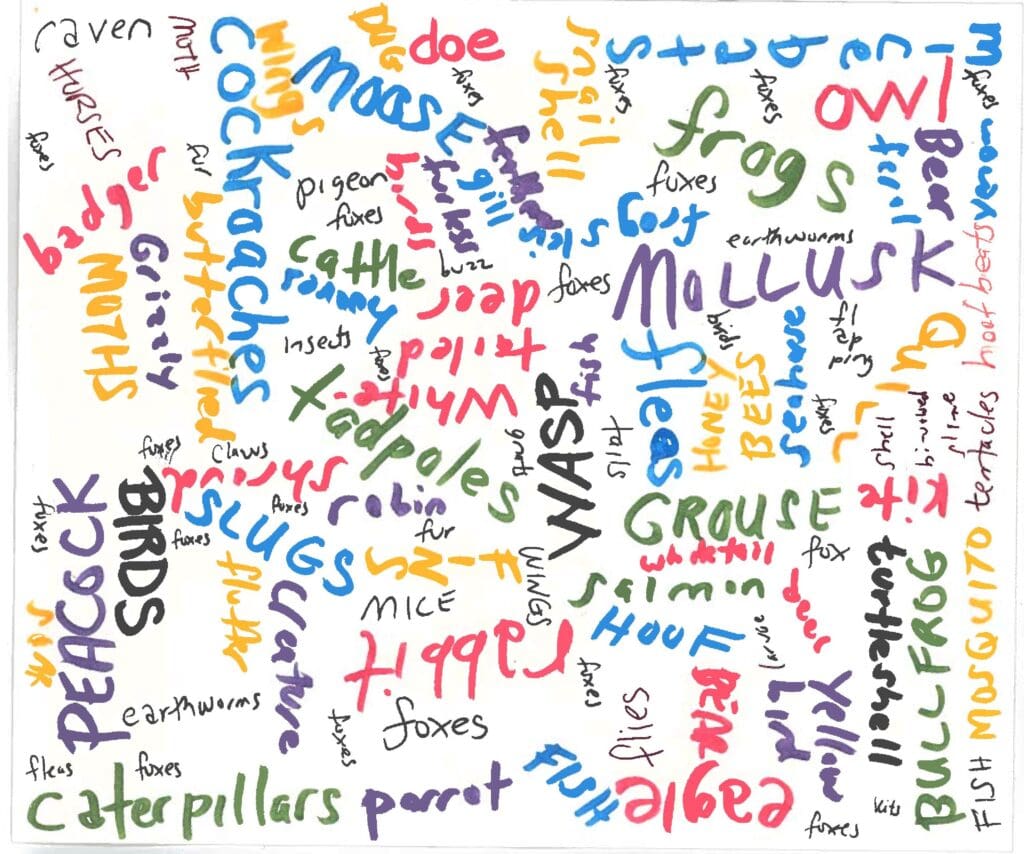

Or, not domesticated or cultivated. What impact does this dual urban/rural lifestyle have on my writing? I’m never sure. Is the rural environment impacting my writing tangibly, or just offering me the required quiet to focus? I assumed the latter, but then I wrote the poems that comprised my book Beautiful Children with Pet Foxes, and my friend and fellow poet Amanda Earl gave me a beautiful visual poem that captured all of the animal references in the book, and the creatures – most of which I’d encountered in some way in my time outside of Toronto – were in such multitude that they were climbing off of the edges of the teeming page.

It wasn’t only animals that infused the poems in that book, but also rivers, mountains, barns, woodstoves, and other decidedly rural metaphors, images and references. The poems explore issues of trauma, complicated family dynamics, mental health crises, and alienation in contemporary life, so as such, they also contain urban and industrial imagery, places that support the business of being human rather than animal or plant – hospitals, pharmacies, all manner of bureaucracies, protests and riots, factories, airports, parking lots, high rises, even dance clubs. But the natural world is what helps me to understand, or at least examine, these ideas through metaphor.

Badger

Or, to urge persistently, nag. The way I live means sometimes – often – it’s tough to ensure that the writing gets done. The Monday-Friday job is essential to maintain the life I’ve carefully constructed for myself, but it is demanding. Sometimes I write in the mornings before the day job. I tried lunch hours; too fragmented, my mind too cluttered. Once I got a grant and took unpaid time off work and wore yoga pants and hoodies for months and wrote every day in silence at the cabin. But that feels like a long time ago now. More recently, I take classes like Hoa Nguyen’s poetry workshop, and Flying Books’ Writing Sex: A Practical Guide to Broaching the Obscene. These focused literary environments keep me motivated, keep me engaged, keep me writing. Opportunities like those underscore why I could never permanently leave the city. But I must constantly push myself to keep writing, keep going, keep organizing and protecting my time.

Grouse

Or, to complain. I have nothing to complain about, except insufficient writing time. This is not an insignificant thing to grouse about, but I am privileged and I acknowledge this – I have a secure fulltime unionized job that I don’t despise in a university setting. I am healthy, with above average energy levels. These privileges allow me to still write while paying bills on a cheap apartment in Toronto and a modest (co-owned with an ex-partner) cabin in the country.

When a grouse takes flight, you may mistake the sound for a distant, revving motor. You’ll wonder who nearby has the motorcycle.

As a child, I once ate grouse, the manifestation of my father’s failure at moose hunting. It tasted like chicken.

Fox

Or, sly like a. Am I cheating the system? Rent in East York, buy east of Toronto. Even two people with good jobs can barely afford Toronto real estate. This is not viable. Toronto disparity is a crisis. This is not news, but it’s worsening. Artists must be creative not just in our work, and in our relationships, but in how we live, how we navigate these financial – urban and rural – landscapes.

Slug

Or, lazy and slow-moving. This is how I feel sometimes. I am energetic, but I tend to take on too much. My mid-40s have been exciting and generative on all levels but sometimes I don’t sleep enough, I don’t eat enough, I don’t slow down enough. I don’t write enough. Every so often, I feel like a slug, a naked ball of slime who has failed to finish anything with real depth, and I curl up, barely moving, on the couch and ooze.

Honey bees

Or, how to help save. Nearby neighbours keep bees and raise chickens. Once when visiting, one of them said “Oh look, that’s one of our bees” dipping into my favourite Echinacea flowers. I wanted to know how she could tell, it’s a bee, how could she know it was one of theirs, did it fly differently, was there a tiny tag on its tiny leg? She is a biologist. She knows about such matters. Also, she is shy. I didn’t want to ask.

Field

Or, of vision. The couple acres of tangled field is where, in warm weather, 4pm meetings with the neighbours take place. Sometimes with a beer, sometimes green tea, always with a meaningful discussion – literature, psychology, politics, gossip. The four households on this side of the small road are rich in personality. The field is also host to evening bonfires. I can lean back and see stars, often shooting stars. I can think. I can think about the sky. I can think about nothing.

Have I forced this exploration of the urban and rural into a dichotomy? That was not my intention, nor is it at all useful. I love the city and I love the woods. I love adrenaline and I love calm. I love socializing and I love solitude. My life and my writing need both extremes. While it’s easy to think in these binaries, they are false, they are false frameworks with which to understand the world or ourselves. The reality is always both, the truths are always on the vast spectrums in between.

And, or, and, or, and. And. And.

Jennifer LoveGrove‘s most recent book is the poetry collection Beautiful Children with Pet Foxes (Book*hug). She is also the author of the Giller Prize–longlisted novel Watch How We Walk, as well as two other poetry collections: I Should Never Have Fired the Sentinel and The Dagger Between Her Teeth. She is currently at work on another novel and a poetry manuscript, and works fulltime in Advancement at the University of Toronto. She divides her time between downtown Toronto and rural Ontario.