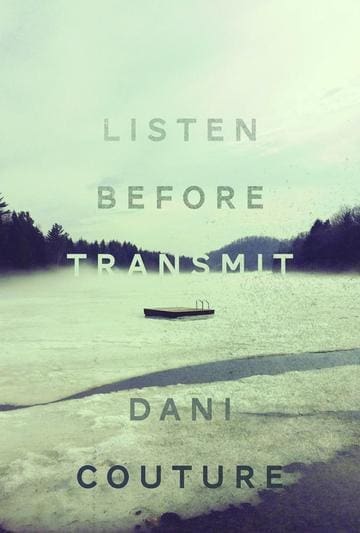

REVIEWING THE SHORTLIST: Listen Before Transmit | By Dani Couture

Wolsak & Wynn | 2018 | 90 Page | $18.00 | Purchase online

Reviewed by Klara du Plessis

Reviewing the Shortlist is a weekly series in which poets shortlisted for our 2019 Book Awards review books written by their peers. Join us for this series until the award winners are announced on June 8, 2019!

In this week’s installment, Klara du Plessis, author of Ekke (Palimpsest Press) – shortlisted for the 2019 Gerald Lampert Memorial Award & the 2019 Pat Lowther Memorial Award – reviews Listen Before Transmit, written by Dani Couture (Wolsak & Wynn) – shortlisted for the 2019 Pat Lowther Memorial Award.

***

A vivid memory from exactly one year ago seats me in a public courtyard in Madrid, sipping a small glass of coffee, reading Dani Couture’s Listen Before Transmit. At the time, I pronounced it a read-every-poem-twice kind of book, as I pleasurably made my way through the linguistic density, the tonal shifts, and emotional load of each poem, then reread it immediately with the newfound familiarity of words I’d made eye contact with before. The words and I would recognize each other as having exchanged confidences in the near past. Now, twelve months later, as I recline around my Montreal apartment with the collection in hand again, I realize that it’s also a read-the-whole-book-twice kind of work. At least. It’s a book that adds layers to the reader’s experience over time, that allows for new discoveries, that shares deeper affective intricacies with each cumulative access point.

Picul. My dictionary suggests piculet, “a tiny, tropical woodpecker with a short tail,” but the internet corrects me. Picul is a traditional, Asian measure of weight. The shoulder-loud of weight one person can bear. “When someone dies, we can say they were reorganized,” writes Couture in “Prototype,” laying the sleek cloak of grief onto the shoulders of the poem.

Visiting a city means, for me, visiting its art. It’s a necessity that revitalizes me, nutritionally. Couture interweaves her collection with references to museums. “Our milk is kept in museums” (“Prototype”), she writes, suggesting, on the one hand, stagnant sustenance, on the other, a hunger for art, for seeing things, for feeding on the richness of the exhibition space. Maybe I insert myself too heavily into interpretation.

For in contrast to my experience of museums, Couture’s museums are enclosures, less expansive than restrictive: “closed into the hour / like an exhibit” (“You Wore Out Your Welcome”). In one museum, the speaker counts fragments of sculptural bodies. Over time, limbs become dismantled. Heads are found, no bodies.

By percentage,

the galleries had more heads than bodies.

Outside of one, a man, granite, holds up the head

of a woman, granite, emancipated from her bodyfrom “Memoir”

Particularly the female body becomes segmented in a way that is more like a sexualized fixation on parts than a historical disintegration of wholes. In another, different kind of private museum, the reader sits in “proximity / to a woman who painted the off-white walls off-white” (“Or In Argument”). In this claustrophobic space, it’s unclear whether the off-white walls are off-white because the woman is caught midway in the act of painting them, or whether she’s layering off-white paint onto walls that are already off-white. The difference being between generative making, and a beige, Sisyphean camouflage.

Foley. An additional sonic layer inserted into the soundscape of a recording after the fact. “Twice, I’ve asked the woods if anyone is there / to no response” (“Or In Argument”). An invocation of all the questions asked into nothingness. If existential questions could be answered through technologically manipulated after-effects, how much more complete would perception be? Real and artificial answers populate interim spaces of consciousness.

Of the collection’s three, untitled sections, the first is my personal favourite for its thematic investigation of the intermediary. Throughout the set of opening poems, Couture draws fine distinctions between definitions, locates the ebb and flow of semantics, sets down borders and then interrogates them. “That there’s a difference / between a spout and funnel,” she wonders, “A fracture / and separation” (“I Come Around with Appetite to Parties”). These are fine nuances of difference, the way liquid pours from a teapot into a teacup, or through the concave shaft of a funnel. Both are methods of measuring liquid through thin corridors into other containers, but one seems cuddly and cosy, and the other scientific and cold. For a moment, I’m reminded of Oana Avasilichioaei’s collection Limbinal, which follows the slippage of difference, lines and fractures and borders with occasionally intersecting parallels of interior/exterior. While “fracture” insinuates more pain than “separation,” the more one considers the thin sliver of division running through any divided entity, the more “you keep splitting only to become one thing” (“Prototype”). A cohesion of difference.

The title poem, “Listen Before Transmit,” (self-identifying as modeled after Peter Gizzi) is constructed from a series of fragments. Each line contains only a phrase from a longer sentence providing partial access to communication, which seems to be crackling in and out of earshot. “The connection severs itself due to” or “their patterns Confute yourself” or “The dial radiates options.” Shards of communication create a boundary between what is provided in the poem and what is withheld, and the ghost limbs of the poem hover suggestively. Simultaneously, the excerpted lines reformulate a new, full poem, and maintain their fractured status as fragments.

Pudendal. The adjectival, external genitals. “Two clefts / that bleed roughly twelve times / a year until they become stateless” (“Pioneer 14”). The menstrual body being both unified and expulsive, both anarchic and dutiful.

In an interview with Open Book, Couture discusses the nature of literary titles. Concerning the title of her most recent collection, she explains that “The term ‘Listen Before Transmit’ or ‘Listen Before Talk (LBT)’ comes from radio communications […] It is, in a loose sense, protocols for engagement when communicating. Waiting for a good moment. The right one. And, of course, listening.” The fragmented, static, and sometimes polyvocal quality of Couture’s writing comes into focus. The concentrated intention of listening aids in articulating both her writing process and the experience of reading her work. Clearly, to listen is most often the best strategy. To absorb an environment sonically before acting. To engage empathetically with another by attempting to understand what they have to say. To write with the strains of multiple voices, interacting. To read with attention to the poet’s voice. To attend a poet’s reading, listening.

Contrails. Another word for vapour trail (“Memoir”). The white line of condensed moisture forming across the sky as an aircraft makes its way through the blue. Linear, white sky-writing. A kind of breathless composition, reminding me of another word that I circled for definition in the poem “Report on the Status of Raccoons on Fern Avenue.” Velaric. The creative of an airstream in the mouth, over the tongue and down the throat to form a clicking sound. An orifice of contrails.

As I start winding down this conversation with Listen Before Transmit, I flip through the pages of my copy one last time, glancing at offhand marginalia. Of course, there is so much more to say, but next to the poem “Sleep Study” I find a scribbled note in light pencil, “Ekke.” It reminds me of a quiet moment of intersection between our respective bodies of work. When Couture writes, “Emails signed / with first initials shouldered against familial names / too common to mean anything,” I think of a few lines from the title poem of my book, “We’re on such intimate terms, when he writes me, he says hi K, / I did not give him leave to abbreviate / me / he takes the initiative / to do in the rest of my spelling.” We both embrace the soft slipping of initials between familiarity, identification, and anonymity. We both consider how our identities are communicated in writing, the degree to which we give and withhold. The violence of abbreviation is mediated by the ability to be recognized in shorthand.

If I sign off this text with K, would I be known? If I sign off this text with KdP, would I be known?

–

Dani Couture is the author of four collections of poetry and the novel Algoma (Invisible Publishing). Her work has been nominated for the Trillium Award for Poetry, received an honour of distinction from the Writers’ Trust of Canada’s Dayne Ogilvie Prize for Emerging LGBTQ Writers and won the ReLit Award for Poetry. Her most recent collection of poetry is Listen Before Transmit (Wolsak & Wynn, 2018).

Klara du Plessis is a poet residing in Montreal. Her debut collection, Ekke, was released from Palimpsest Press in 2018; and her chapbook, Wax Lyrical—shortlisted for the bpNichol Chapbook Award—was published by Anstruther Press in 2015. Klara is the editor for carte blanche magazine, a PhD English Literature student at Concordia University, and currently expanding her curatorial practice to include experimental Deep Curation poetry reading events. Follow her @ToMakePoesis.