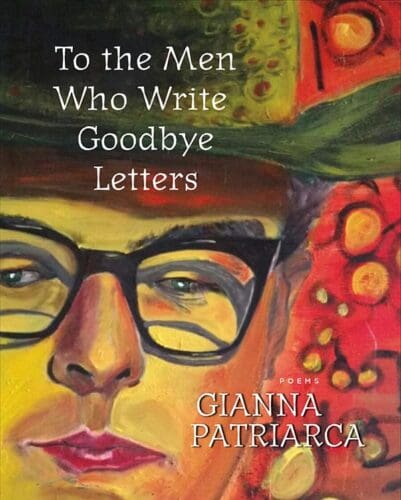

Final Breaths on the Tongue: Review of Gianna Patriarca’s To the Men Who Write Goodbye Letters

Reviewed by Renée M. Sgroi

Gianna Patriarca’s latest poetry collection, To the Men Who Write Goodbye Letters (Inanna, 2020) balances the universal and the specific. Using feminist and multilingual lenses, Patriarca’s poems are, like the stones she has written about in a previous poetry collection, unapologetically hard-edged, honest, and as a result absolutely compelling.

Gianna Patriarca’s latest poetry collection, To the Men Who Write Goodbye Letters (Inanna, 2020) balances the universal and the specific. Using feminist and multilingual lenses, Patriarca’s poems are, like the stones she has written about in a previous poetry collection, unapologetically hard-edged, honest, and as a result absolutely compelling.

The collection begins with the poem “Die So I Can Write About It”, which anchors the book’s focus on life, death, absence, and the imperative to bear witness through writing. Patriarca’s voice is decidedly and refreshingly pragmatic, and this first poem asks: “was i too loud / fat awkward / my voice too clear it frightened you”. The clarity of the poetic voice here succeeds in establishing whole worlds with just a few lines or words. For instance, “Peasant” evokes a Canadian classroom where the student observes the teacher: “she pointed to the last desk / in the back row / by the open window / where the scents i exuded / less brazen”. The subtle cruelty of the teacher’s action is palpably rendered here, and the sparseness of Patriarca’s lines reveal incomparable skill. “Balance” offers a similar demonstration of skill, and speaks to the inevitable passage of time and to the loss of culture. The poem begins: “when all the aunts who were / great cooks are gone / cravings linger”. In just three short lines, Patriarca calls up that sense of deep longing for memories that, like language, slip so easily through our fingers.

The book is divided into three sections: “To the Men Who Write Goodbye Letters”, “Parts of Her”, and “Ten Days in January”, and the first section focuses on the title men and their departures (some of whom depart without, in fact, leaving a trace). Included in this section are poems about Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Anthony Bourdain (whom the poet also quotes in an epigraph), fathers, husbands, and friends. The spectre of suicide is heavily implied in this section, including in the book’s title poem, which begins, “only fucked up romantics / write letters that become poems”. The suggestion here is that the poem’s speaker has written letters that have morphed into poetry, yet Patriarca toys with that idea in the fourth stanza, which reads, “i don’t write letters / i organize i sanitize / live in a clean house”. The question raised here then is who writes letters? It appears that the “you” addressed in the poem did not, that this man or men instead created an absence: “i wish you had written / that letter to me back then / i might have convinced you / exiting / was the wrong thing to do”. This gaping absence is mirrored in poems such as “Tony”, where “a blank sheet of paper / on a side desk untouched / no finger prints on the blue pen / a glass half empty or half full” both sit untouched and unconsumed, as well as in the poem titled, “The Jump”. Familiar to Torontonians most unfortunately as the site of numerous suicides and attempted suicides, the Bloor Viaduct is the setting for the figure of Leonardo: “he flew over a bridge / where the space below was wide / open and free”.

The reasons for Leonardo’s jump have to do in part with the disjuncture that stems from the immigrant experience: “every immigrant story begins / with the elusive American dream / even if the dream is set in a Canadian landscape” (“The Jump”). Patriarca mines this experience especially in relation to language, “as we abandon favourite words / drop them over bridges wait / to see how long it takes them to land” (“The Jump”). The poet’s concern with the loss of language is a thread that runs throughout the entire collection, yet “Words”, in this first section, sets up the duality of presence and absence that marks this large feature of the immigrant experience. Patriarca writes: “my words have no neighbourhood / in which to play / no streets to loiter”, and later in the poem, “there is a country somewhere / so long undreamed / almost forgotten / where i once played” (“Words”). In a few short lines, Patriarca elegantly renders the loss of that relationship between language and place.

The poet’s inability to mark that territory of language, to find that “neighbourhood”, is further heightened in what for me are the two strongest sections of the book: “Parts of Her” and “Ten Days in January”. In “Parts of Her”, Patriarca has included poems written in her Ciociaro dialect. “Dentr a stá cucina” and “Stamattina” appear beside their English translations, with the Ciociaro poems positioned first. As the daughter of southern Italian immigrants myself, I read these poems (and the order in which they appear) as political acts that highlight the attempted erasure of the world’s dialects and “unofficial” languages into the standardized languages of their countries of origin and, as a result, speak those dialects or languages and their cultures back into the conversation.

In addition to the Ciociaro poems, there were many moments in my reading where I felt the ghost of Italian and its dialects underwriting so many of the poems solely written in English. For instance, I hear the rhythm of “Die So I Can Write About It”, in its unwritten (and perhaps for the poet, unimagined) Italian translation, yet this demonstrates Patriarca’s ability to cross from one language into the next, bringing with her the power and musculature of the original language. However, as anyone who speaks or has attempted to speak another language can attest, language links are held most closely in relation to their communities of speakers. As such, the mother tongue (and indeed, my play on “mother tongue” is intentional) is most significant in the “Ten Days in January” section, where the poet addresses her mother’s death.

For anyone who has experienced a similar loss, this final section of the book will resonate, as Patriarca’s powers of observation are here on full display. For example, “The Last Room” details how “we never would have imagined / the last room of your life / would be the sixth floor / of a building on Church Street / south of Bloor / in this city that has pretended / to be home / for fifty nine years”. The striking juxtaposition of the precise location of death on the hospital’s sixth floor against a city that was not truly the mother’s home speaks to Patriarca’s ability to blend the specific and the universal in just a few words, leaving the reader both heartbroken by the poem’s subject, but also dazzled by its delicate turns. “Language” accomplishes this as well yet with added dimensions. Written in English and then translated into standard Italian (not Ciociaro), this poem suggests a double move away from dialect and into a degree of acquiescence of the dominant language that perhaps has become the poet’s, but is ultimately, not fully her own. The poignancy and pain of this double move, combined with the mother’s passing are razor-sharp in their execution: “when my mother died / so did our language”. This generative language between a mother and daughter was “the one we spoke / each day at the kitchen table / each night by the hum / of the television / on the telephone between visits”. “Language” ends with a powerfully ambivalent image and with the poet’s recognition that she is the keeper of “old languages”, and that, as for the ‘mother tongue’: “i will hold it safe / in the limbo of my gut”.

While there are many more poems to recommend this collection, I’ll end this review by focusing on one final point. What is fascinating in this work is Patriarca’s fondness for caesura. The poet’s ready use of this device sets up a dialogic quality to the work that echoes the multiplicity of languages, figures, fissures, and points of observation that emerge from these pages. In dialogue with the world and with her telescopic powers of seeing, these moments of caesura are perhaps best represented by the epigraph that appears at start of the book, where Patriarca writes in both Italian and English, “among the pages / find a life / as ordinary as any life / as splendid as any life / all of this / in one good poem”. To the Men Who Write Goodbye Letters offers readers much more than “one good poem”. Through her rich and deeply moving poetry, Gianna Patriarca guides us on a reflective journey through life, language, and loss that is truly splendid.

To the Men Who Write Goodbye Letters: poems by Gianna Patriarca (Inanna, 2020) 104 Pages

Renée M. Sgroi (she/her) won runner up in the UK’s 2020 erbacce poetry prize, and her debut poetry collection, life print, in points was published last year by erbacce-press. Her poetry has appeared in The Prairie Journal, The Beliveau Review, Accenti Magazine, Lummox (US), The Wild Word (Germany), Poetry Pause, Synaeresis and The Banister. In 2018, she edited the poetry anthology, Written Tenfold (Poetry Friendly Press). Renée is the past president of the Brooklin Poetry Society (Brooklin, Ontario), and can sometimes be found blogging at her website, https://reneemsgroi.com.