That Sinking Feeling: in the broken boat with Daniela Elza

Reviewed by Louise Carson.

It was with a sinking feeling in my gut that I started to read Daniela Elza’s the broken boat. Oh no. The end of a marriage. The loss of a husband, intimacy. The breaking of something that the poet had thought would last forever. My own thirty-five year old trauma began to bubble up in all its ugliness – the scars tingled.

It was with a sinking feeling in my gut that I started to read Daniela Elza’s the broken boat. Oh no. The end of a marriage. The loss of a husband, intimacy. The breaking of something that the poet had thought would last forever. My own thirty-five year old trauma began to bubble up in all its ugliness – the scars tingled.

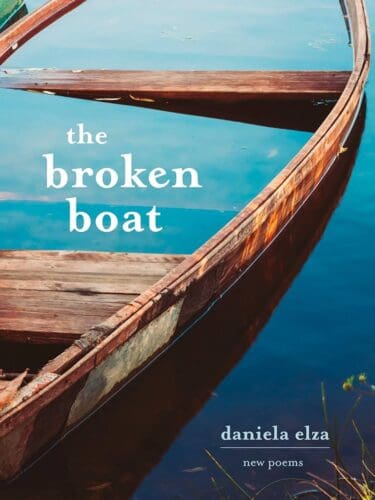

Calm down, I told myself, looking at the image of a half-sunken old row boat on the book’s front cover. Drink your tea and read just a little at a time. So I began. And it wasn’t long before I was no longer thinking about myself but was sucked into the poet’s world, her experiences, and the way she was presenting them.

The book’s epitaph, a long quote from Rilke’s Sonnets to Orpheus, warns “Be ahead of all parting, as though it already were / behind you, like the winter that has just gone by.” So, as winter signals the death of many living things and the pressing down into near death of many others, we know we are in for some misery. Cold misery. And it seems that the poet was not prepared.

In ‘autobiography of grief’, the introductory poem, before the first of six sections begins, we are invited into “the broken boat in which / we sleep – our backs to each other.” And so this book – this autobiography of grief – begins on its first page with such words as heaviest, parting, unfinished, homeless, disperse, hammered, snapped, nailed, and burns. Not so cold, then, this misery. But a long, long winter.

Every nuance of the former relationship must be examined. It seems to me that the poems are sequenced more or less chronologically. Early in section one – wintering through – in ‘this is not a rehearsal’ we feel that the participants are still okay in the relationship. Day and night follow each other in orderly fashion. Geometrical shapes move, define their life together. “you draw me a world / where we fall asleep – / heads next to each other / two circles (intersecting (dreaming”. The opening brackets emphasize the married couple’s separateness one from the other, don’t you think? The loss of enclosure within the relationship.

Yet, in – ‘tossing & turning’ – comes the metaphor of the boat for the marriage, and she asks “what will they toss in it”, the way you toss, say a life preserver into the bottom of your boat before you push off from shore. The life preserver in this case is a fragment of two italicized words that precede the previous line. “such love”. Somehow we doubt such a small reminder will save the whole. Not that a life preserver is mentioned, of course. Rather, words like: a/part; s/nagged; sp/lit; f/ear appear. Then comes “such love”, sadly, too late.

Which brings us to one of the techniques Elza employs, “sp/litting” words to reveal another interior meaning. She does this both with obliques or italics as in ‘winter light’. Words like skin; across; through; shard are scattered through the first stanzas, and without their non-italicized parts become kin…cross…rough…hard. A little poem within the poem.

Once you get used to this way of extracting the most from a word, you look at the other ways words and punctuation and spaces are used. Almost always there are various extra spaces between single words and phrases. If I read the poems aloud and include the spaces, I either (in a way) hyperventilate or stagger. The effects of extreme emotion. Observe the spaces as pauses as you read “she steps cautiously between / words. sp/lit.” and you will see what I mean. (‘tossing & turning’, page 4). I can flip to most pages in the book and find examples of this. Page 34, for example, in one of the untitled poems of the section self-portraits.

is this

being

part of

or is it parting?

(I have approximated the spacing.) Not just spacing separates bits of poems from the rest of the text. We see that all the italicized words make up another small poem. Here they are but without the spacing: “you / untitled. / is this / being / part of / parting?” You can take this even further as I did and read all of the twenty four poems in self-portraits again, but just the italicized words. Probably Elza didn’t mean for her readers to do this – perhaps she did?

One of the more difficult poems (for me) is ‘late afternoon woman’ (page 14), a pensive walk on the beach. I confess I had to read it many times to tease out my interpretation. This poem continues with widely spaced sentence fragments and dropped lines to open up to the reader – slow and curious enough to follow – different visual pathways than the left to right, left to right. Here are the stacked phrases which were flushed furthest right on the page. “my tired limbs / as if it were / on my hand. // I know I live / this gift / through pebbled dreams // I crouch / the sea rejected / to swallow me –”

Contrast this ‘difficult’ poem with the delicate, clear ‘the difficulty of such beginnings’. A tree thought dead sprouts a new leaf and “what we are not // rises like sorrow between us.” so “that this is not / the beginning but a kind of / beginning / (after –”.

In ‘tossing & turning II’, which brings us back to the boat, the marriage, the marriage bed, the ending of the relationship is disclosed, I assume, them still love-making but, in the first verse “your hands / reaching. / and each time it’s like / leaving.” And the last two lines “and each time it feels like / sincerely yours,” Ouch! I remember.

I’ve already mentioned a few poems from the section self-portraits, which takes up the second quarter of the book, but I’d like to return there. After I read the first few poems, I decided to read

the whole section right through, and I’m glad I did, as this led me to compare and contrast certain of the poems and find the themes that tie the poems together. These poems are simpler, easier to understand, more direct than the poems in the first section, a dialogue both internal and with the husband, trying to understand and grieve. “Grief returns like a fifth season”. (page 38) Lovely.

There are religious aspects in these poems as well as frequent references to lights. Loving the other – “the vows we made…ignore traffic lights. and I have grown clumsy in my worship.” (page 35) And on page 32 – “Was it your light that lit up things in the world?” Makes me think of something I might have heard in church.

At the end of section two she’s beginning to absorb their separation, to the point of being able to ask (in what I hear as a somewhat appalled voice) “will you break so for love again?”.

The illustration for section three – eros/ions – is illuminating: two fish heads in a bowl, a ring next to the bowl, two fishhooks dangle nearby. The poet’s real panic appears in this section. She names it on page 53. “your panic / sets something ablaze”. Eros is leaving and leaving a trail of sparks at that. A tree faces a firing squad and “The alley bristles” where “shifting shadows…will pounce on you”. (page 54) Everyday objects in her home threaten. A doctor is mentioned more than once, which implies sickness.

In the short fourth section of the book – autobiography of grief II – comes the splitting of property and of physical love. The husband has “become the man down the hallway / something to bump into in the dark.” (page 73) and “a disappearing tail of lights / in the mist.” (page 76)

The title poem of section five is ‘afloat (on the emotion of bodies’ and she’s still using we and us until at the end of the poem a timid I emerges. A few pages later in ‘without a sound’ the poem is full of I! But she wants to “grieve your loss / the way you would’ve wanted me to / without a sound / without a word.” So she’s not quite free yet.

Many of the poems in this section discuss the poet’s relationship with words, a sign that she is forgetting her husband, and her creativity is re-asserting itself. But as in ‘I talk to you here’ “the poetry crones tease me” and laugh at her, she conflates her husband and their life together in the following poem ‘at a distance’, which opens with “yesterday I mistook you for a poem”, with her art. We know all will be well when she ends the poem with “and the light still fools me into singing.” (I would have been tempted to end the book with this line.)

The poem that ends that section – ‘in the surf’ – is full of lovely language and repetition of the word breaks. “how we break on these shores”; “break down into tears.”; “how sunset breaks my fall into the dark.”; and, speaking about a heart-shaped rock “how it too was broken before / it was rolled smooth”.

The final section – life as conceptual art – is a long poems broken into a few sub-sections. The relationship is beginning to lose its intensity as she assembles images of their life together, the house becoming “the warehouse of our together.” (page 95) The turn comes when she introduces the lilacs that have flowered against a wall across the street, volunteers that no one planted. They become her “unlikely hope” (page 98), two words, which, juxtaposed, induce sadness in me.

As (page 96) “some days we are the space between / the paintings”, she asks “why did you put these canvases on our walls?”. There is no answer until, inevitably, “in time I am hung on the wall / alongside all my questions.” (page 98) until, eventually, all her experiences “will be moved to the basement / of your memory.” And that’s where she takes her leave of us, sitting in the basement, listening to “the copper music” of her house’s plumbing, where “the echoes keep running into each other / just like we used to.”

Sad words those: just like we used to.

Purchase the broken boat by Daniela Elza from Mother Tongue Publishing

Louise Carson has published nine books including mysteries, historical fiction and poetry. Her collection A Clearing was published by Signature Editions in 2015. One of her books In Which, Broken Rules Press, was shortlisted for a 2019 Quebec Writers’ Federation award. She has recently had work in Grain, Event and Queen’s Quarterly and online with Montreal Serai and carte blanche. Her next collection Dog Poems will appear in 2020 from Aeolus House. Though born in Montreal, she has lived beyond the West Island for most of her life.

Daniela Elza grew up and lived on three continents before immigrating to Canada in 1999. Her poetry collections are the weight of dew (Mother Tongue Publishing, 2012), the book of It (2011), and milk tooth bane bone (Leaf, 2013). the broken boat is her fourth book. In 2011, Daniela earned her doctorate in Philosophy of Education from Simon Fraser University. She continues to contribute to the field of Poetic Inquiry. Her Masters degrees are in English Philology, and Linguistics (TESL/TEFL). In the literary community, Daniela facilitates writing workshops, mentors emerging writers, edits, and performs. She coordinates and hosts a reading series (Twisted Poets Literary Salon at Hood29 on Main St.), that shines a light on hundreds of published and emerging writers. Used to crossing geographic, cultural and semantic borders, Daniela’s work often dwells in liminal, and in between spaces between word and world, and the inherent possibilities for transformation through the attention. Daniela’s poetry has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize, Best of the Net Anthology, and has won numerous contests. Her essay Bringing the Roots Home was nominated for the 2018 Pushcart Prize. She is currently exploring her passion for the personal and lyric essay. Daniela lives in Vancouver, and works at the Bolton Academy for Spoken Arts.