ON NOT WRITING: POETRY AND TRAVEL ACROSS NORTH AMERICA

by JC Bouchard

—

Poets constantly make creative and technical choices in their poetry. They also make choices in their lives from which, in many cases, their work is largely drawn. As a young aspiring poet earning a B.A. in English Literature at a small university in northern Ontario, I wanted to choose something visceral, unpredictable, and with immediate consequences.

One morning in a second-year English literature course, during a lecture on the satire of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, I suddenly packed up my books and left the classroom. That week I secured a refund of one semester’s tuition: a measly $3,500 that seemed like an enormous sum to a 20-something-year-old. Two weeks later I bought a camping backpack and a Greyhound Discovery Pass (now defunct) that granted me one month of unlimited travel in North America (except east of Montreal). The choice was simple: go west and see my country rather than learn about the people in someone else’s. It was a naive and impulsive decision that I would never take back. I never did earn that B.A.

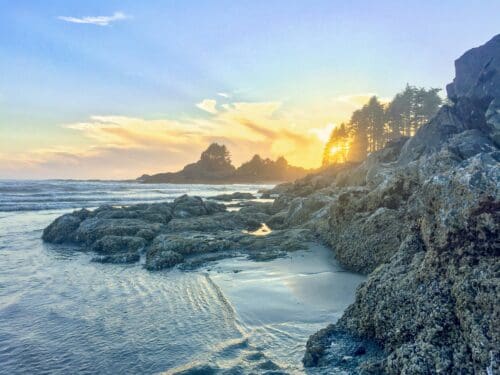

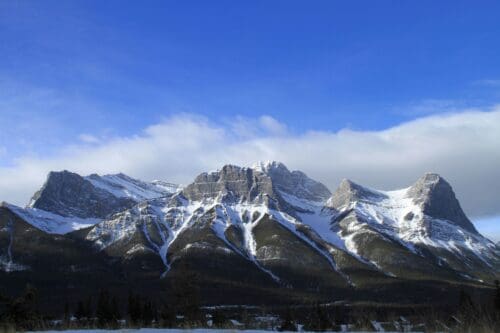

After practically living on public buses to and from Alberta and British Columbia—Canmore, Tofino, Nanaimo, Edmonton, Jasper, and Victoria—I returned to Ontario without money, education, or a worthwhile collection of poetry, the only thing that might have made the trip at least artistically justified. Two years later in Ottawa, after earning a college diploma and writing as many poems as I could, I cleared out my bachelor apartment and set off again, this time by car with a friend back to British Columbia. From there I set off on another Greyhound bus throughout the United States.

About one week later I found myself in a desert two hours outside of San Francisco; the bus had broken down in the middle of the night. It was going to take over eight hours for another bus to come. I sat in the dry dirt and watched the sun rise over a field, a pen and notepad in my lap, and thought of how to capture my experiences up until then: the shifting landscapes; a woman spun on speed in the bus; a middle-aged bar singer fighting for the custody of her son; the foggy mountains west of Calgary; the hitchhiking hippies in Tofino; the vast country between me and my final destination; how far I was from home; that I was, for the first time, frightened. Instead of writing, I put the pen and notepad back in my pocket and waited. It instantly felt like I would betray the moment if I tried to capture it on paper, like suddenly stopping in the middle of sex to describe its sensations, something no person in their right mind would ever do.

I didn’t write anything substantial my entire time in the U.S.—through Washington, Oregon, California, Nevada, Colorado, Omaha, Ohio, Illinois, New York, and all the way back to Ottawa where I once again found myself poor and with little creative or professional opportunities. The only exception was a few stanzas which were the basis of a poem that became one of my first publications. How odd that an aspiring poet would travel and not write any poetry, at least not at any great length. It almost seemed like a waste to not document what was to me a significant experience. But of course, I still had the experience. It was not as if it would somehow dissolve and disappear by keeping it off the page.

I realized at the end of it all that poetry was not why I was traveling. At the time the literary efficacy from the two North American trips seemed frivolous. Composition came eventually but only when the traveling was over, at which point the experiences, circumstances, landscapes, and people had sunk in, when I could fully acknowledge and appreciate what had happened and how it all felt. There was this perpetual, nagging feeling: live out my experience rather than record it, cease from analyzing it like stanzas or lines in a poem. In doing so I felt totally emotionally and mentally engaged in my surroundings, probably more than I ever had before. Anything in my travels worth telling about imprinted upon me. Perhaps there were feelings, ideas, and characters that were lost because I didn’t write them down. But I thought, let them be lost, let them be as they are. I let everything slowly bloom in my memory.

The accumulation of experiences through raw interactions can also be a form of poetic composition. Paying attention with openness and empathy rather than scrutiny gives way to ideas, emotional sensitivity, and perspectives that we don’t think we possess. Of course, anything of literary value requires a great deal of work and, for many, unending tedium. But before we actually sit down to write and make creative choices, we may benefit from a period of reflection free from the constraints of form, technique, metaphor, and all the hallmarks of good poetry. This term of reflection may help us understand what constitutes our individual voices. We do this in numerous ways, the most common being actual writing, even if only as an exercise. But for me, the exercise was spending weeks going to provinces, states, and cities which I had never been, interacting with people who I had never met, not intellectually concerned with how I might fit them into poetic concepts.

I am not a world traveler, nor do I suggest we should never write while on the road. Creative processes as it relates to travelling can inexplicably change from one journey to the next. For example, my last trip was to Iceland, and I wrote down any observation that came to mind with no intention to finish something whole. This was in stark contrast to my previous excursions. It was a compulsion, not a caveat.

I believe there is tremendous value when we are able to recognize the many ways traveling inform our poetry, even when not writing about them, when our experiences commit themselves to memory rather than a page, creating within us a map of an emotional territory. It’s essential to have personal goals and guidelines in our work which we discover over time, rather than arbitrary constrictions that seem good for some but feel foreign to others. Writing poetry is hard enough as it is without forcing upon ourselves external, unnatural rules that are counter-intuitive to how each of us independently thinks and works. Anyway, when all things are considered, perhaps the idea of a wanderlust poet is just another cliche—but so what.

In Iceland, I wrote but did not complete. Sputtering on a bus around North America, I barely wrote at all. Both experiences, and how I chose to recognize them in poetry, still impact how and what I write today, and hopefully will continue to influence me for years to come or, at least, until the next trip.

Whenever you find yourself in a foreign country, perhaps for the very first time, you can choose not to write and without suffering some great loss of life. The only loss is if you cannot engage with your myriad emotions, and the places and people that bring them to life.

—

JC BOUCHARD was born in Elliot Lake, Ontario and lives in Toronto. His poetry has appeared in Arc Poetry Magazine, Hart House Review (Winter Supplement), and untethered. He the author of two poetry chapbooks: Portraits (In/Words Press) and WOOL WATER (words(on)pages press).