River Verse, a review of beholden: a poem as long as the river by Rita Wong and Fred Wah | Cynthia Sharp

Talonbooks 2018

Illustrated

ISBN: 978-1772012118

Pages: 137

Review previously published in The Miramichi Review and Canadian Poetry Review

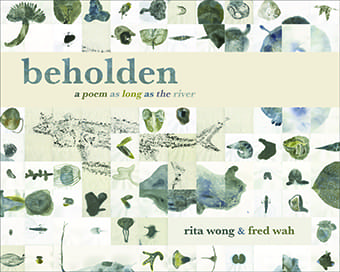

Rita Wong and Fred Wah’s 2018 collaboration beholden: a poem as long as the river from Talonbooks with cover illustrations by Genevieve Robertson explores the ecology of the Columbia River, which has had fourteen dams intercept it. The project began as an interdisciplinary endeavour in support and harmony with the Columbia River and affected First Nations with Wong and Wah each contributing an individual poem composed in a unison of time and place, alone and together. Their poems, along with Robertson’s artwork, were originally part of River Relations: A Beholder’s Share of the Columbia River, an interdisciplinary research project of mixed media – print, paintings, drawings, photos, video and verse – undertaken as a response to the damming and development of the Columbia River in British Columbia, Washington and Oregon. Shortlisted for the Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize, the book features the map and sketches by Emily Carr Art School instructor Nick Conbere that was originally a 114 foot installation, now laid out through 137 tangible pages, Fred Wah’s poem in type starting along the top and Rita Wong’s by hand on the other side of the bank, a reflection of how Wah and Wong wrote their unique and similar experiences from opposite sides of the river, listening in solitude to the same water, crossing over in places. The interactive nature of the standalone poetry laid out with a map appeals to the senses, the softness of smooth pages flowing like a river, what was once a long, winding, real life art display that readers walked along now a permanent resource in book form. While the design is inviting, the heart of the project is more subtle. It emerges from a perspective of intentional respect, grounded in listening and service as an entry point

The magic of the writing stems from the authors’ proximity to their source with patience and reverence for the water, the biosphere and the myriads of cultures, human and animal, living in harmony with it, to witness and advocate as truthfully as possible in gentle storytelling, encouraging all of us to honour our own voice and place in water for the time that we exist. The overall mood is informed by purposeful, humble listening. The strength of “beholden” is deeper than its technical craft – it’s honesty, letting go of preconceived ideas or assumptions, and approaching the river with humility. This comes out in subtleties, such as the choice to forego capitals on the title or author names, as well as in the long run of gratitude and belonging that emerges through the writing, the way the land claims those who commune with it. In the interview at the back, Fred Wah explains, “I found in approaching our project, after we had decided to do this poem as long as the river, that I had to first shed my preconceptions, not about the river, but about what I could bring to the river. One of the greatest experiences of making this composition was finding out that I had to listen to the river to hear what resonations were available…Language was something that bounced back from the river” (Wah, 139). This echoes through the poetry: “we need to ask permission of the river first” (144), Wong says.

This attentiveness flows like rivers into subsidiaries, as smooth as stones washed in consistent, enduring current: “ceremony by ceremony the river people live the wisdom that comes in dreams always remembering the water” (91), Wong writes. Her work is sprinkled with meaningful imagery from “sunning turtles” (10) to “starlight savvy” (132), compassion the secret to the vibrance of her verse, “trees and terrain, song and starlight” (80), evoking the unique atmosphere of place surrounding the Columbia. “the water slips through your fingers but teaches temperature” (120) Wong writes. We trace her words with our fingertips, “generation by generation as blood memory, cell memory, is river memory” (77), our palms and fingers flowing through the river as we read, as though we are in a canoe on the water breathing in words, the layout of the poets weaving through each other the way water carries all. We are one with their poems, part of the “biotextual” concept of flow. As Wong imparts, though we are part of industrialization, we can at least be aware of our use of electricity, not to be disabled by guilt but to have respect for how electricity is made, what it costs the environment and not to waste it or use it excessively outside of necessity. We are part of the twenty-first century, but we can guide its course

For Wah, listening starts from beneath the river, his search for language alluded to in the collocation of grammar diction through his poem. “but remember to return those salmon bones to the water turning truth into a verb” (71), he advises, building an active, changing grammar that implies everything is capable of transformation. Phrases such as “at the end of isness” create musicality in new words. The candor and oration he hears from the riverbed revitalizes our use of English and adapts it to a more considerate and reconciliatory tone, while at the same time acknowledging the limitations of language and our complicity in the destruction we face. Wah’s words turn language into power of its own, with permission to move form, from noun to verb, to action, permission to loosen from tightly held concrete, logging and containment to friction and movement, at both a cellular and comprehensive level. He speaks to the cells inside us along with the construct of ideas and politics, reminding us that treaties are living agreements. A powerful drumming discourse is found in his alliteration and rhythm that opens our synapses to wisdom, to know that we are one life that will fade into the greater silence that absorbs all. Beginning and ending with “cadence” (3) and gratitude, Wah closes the journey with “hello Ocean, River’s mouth thanks for listening to this stream of words become the surf and now the River’s voice is free to roar with the sound of silence” (135-136).

River Relations: A Beholder’s Share of the Columbia River, and beholden: a poem as long as the riverredefine poetry and its cultural significance in harmony with art and social sciences as a means to honour many voices, all the water and words flowing through a collective of academic disciplines. This partnership invites dialogue across fields of study and experience to place poetry as part of resistance, culture, history and change, this story, this time, these voices and truths, reminding us that we are water and “water remembers,” that in all the complexity of our twenty-first century industrialized lives we are still elements, memory, part of the earth, whether we poison ourselves and planet or live as graciously as we reasonably can, that we are present carrying past and influencing future. We too are water. The intertextuality of beholden carries through many senses at once, reinforcing the voice of the river as heard through poets Wong and Wah, a message that resonates strongly for its choice to begin by letting go and listening to “the words that the river gave us.”

beholden: a poem as long as the river has a tremendous impact on those who experience it. “as the ocean accepts the river” (136), so we too absorb this practice of listening with intent to serve through words, actions, voice and being, in this time in all its complexity and beauty, to open ourselves to awareness for sustainability and well-being, to walk with reverence for all life, creating our own river verse in classrooms, life and daily interactions, playing with meaning through awakened understanding.

Rita Wong lives and works on unceded Coast Salish territories, also known as Vancouver. Dedicated to questions of water justice, decolonization, and ecology, she is the author of monkeypuzzle (Press Gang, 1998), forage (Nightwood Editions, 2007), sybil unrest (Line Books, 2008, with Larissa Lai), undercurrent (Nightwood Editions, 2015), and perpetual (Nightwood Editions, 2015, with Cindy Mochizuki), as well as the co-editor of downstream: reimagining water (Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2016, with Dorothy Christian).

Fred Wah was born in Swift Current, Saskatchewan, in 1939, and he grew up in the West Kootenay region of British Columbia. Studying at UBC in the early 1960s, he was one of the founding editors of the poetry newsletter TISH. After graduate work with Robert Creeley at the University of New Mexico and with Charles Olson at SUNY, Buffalo, he returned to the Kootenays in the late 1960s, founding the writing program at DTUC before moving on to teach at the University of Calgary. A pioneer of online publishing, he has mentored a generation of some of the most exciting new voices in poetry today. Of his seventeen books of poetry, is a door received the BC Book Prize, Waiting For Saskatchewan received the Governor-General’s Award and So Far was awarded the Stephanson Award for Poetry. Diamond Grill, a biofiction about hybridity and growing up in a small-town Chinese-Canadian café won the Howard O’Hagan Award for Short Fiction, and his collection of critical writing, Faking It: Poetics and Hybridity, received the Gabrielle Roy Prize. Wah was appointed to the Order of Canada in 2012. He served as Canada’s Parliamentary Poet Laureate from 2011 to 2013.

Cynthia Sharp holds an MFA in creative writing and an Honours BA in literature. She was a WIN Poet Laureate and the City of Richmond’s Writer in Residence. Her poetry, fiction and reviews have been published in journals such as CV2, Prism, Pocket Lint, The Pitkin Review and untethered and nominated for the Pushcart Prize and Best of the Net Anthology. She’s the author of Ordinary Light, a first prize winner in the SCWES 2023 Book Awards for BC Authors, Rainforest in Russet and The Light Bearers in the Sand Dollar Graviton, as well as the editor of Poetic Portions.