NPM AND BEYOND: 10,000 HOURS, PART 1

National Poetry Month, for 2017, is celebrating the time of time. When Kate Hargreaves took that theme and ran with it for our poster and bookmark designs, she said that what she first thinks of when she hears “time” is editing: drafts, drafts, and more drafts. This got us to thinking: they say it takes 10,000 hours to master a skill, right? Well, what do those 10,000 hours look like? We’re excited to sit down with some of the poets shortlisted for our 2017 book awards, as well as some poets included in our 2017 Poem in Your Pocket Day booklet, to find out what their 10,000 hour journey has looked like.

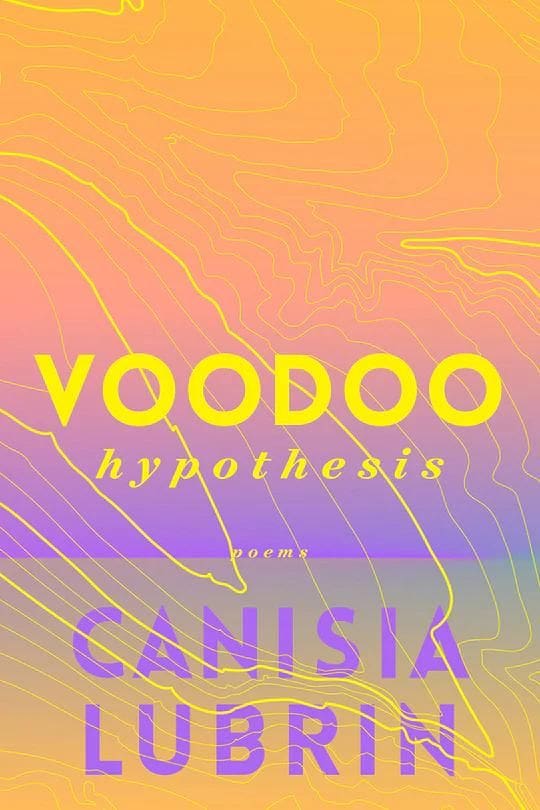

Today we’re chatting with Steven Heighton (whose book The Waking Comes Late recently won the Governor General’s Prize for Poetry, and is shortlisted for our Raymond Souster Award) and Johanna Skibsrud (whose latest collection of poetry, The Description of the World, is shortlisted for our Pat Lowther Memorial Award) as well as Souvankham Thammavongsa and Canisia Lubrin, who are both included in the Poem in Your Pocket Day booklet. We wanted to ask them about the highs, lows, and strategies of their poetry careers so far.

LCP: What have been some notable moments in your poetry “career”? Achievements as well as disappointments.

Souvankham Thammavongsa: The day my first book was published. Almost fourteen years ago. It changed nothing. That meant something to me.

Steven Heighton: I’m lucky that I was disappointed in 1995 when I was a GG finalist and didn’t win. Winning then might have confirmed me in certain bad habits I was developing. Once you’re middle-aged, “achievements” can’t go to your head the way they can when you’re young. By 55 you’ve figured out that applause can’t make you happy (though indifference, unfairly, can make you unhappy). Above all, you’ve learned that within weeks of any achievement you’ll find yourself struggling and failing in some new way.

Johanna Skibsrud: Winning second prize in a children’s poetry contest at the age of nine; My father printing out my winning poem on cardstock and distributing it to our friends; Self-publishing a poetry zine in high school with my friend, Rebecca Silver Slayter, and distributing it to our friends; having a poem accepted in Pottersfield Portfolio; having fifty more rejected from everywhere else; learning that Gaspereau Press would be publishing my first poetry manuscript and working on that manuscript with Kate Kennedy and Andrew Steeves; reading the first positive review of my first manuscript; reading the first disparaging review of my first manuscript; writing the first poems from this new collection while staying at the Elizabeth Bishop House in Great Village, NS; working with Paul Vermeersch; trading poems with Kate Hall; being nominated for the Pat Lowther Award.

Canisia Lubrin: Every moment is notable for me. I dread the day that this ceases to be true.

LCP: What is your relationship with publishing in literary magazines?

ST: I love them. They are there for you before you have an idea of what you want your work to look like.

CL: I’m not sure that I would classify my publishing in magazines as a relationship. Literary magazines entered my purview when I was studying Creative Writing at York University. My instructors, writers all, gave the lot of us much advice and schooled us on how to submit, how to assess our work for calls, etc.. The first year after I graduated this program, I did as I had been encouraged to do. My work was consistently rejected: 100% rejection rate. I decided I would stop sending work out and just write. So, I did. Fast-forward four years, I graduate the Guelph-Humber MFA program with no publishing credits and decide, again, to send out a few poems. I had a new confidence after having spent one semester as Dionne Brand’s student, an experience for which words have not yet been invented. Nine out of the ten poems I sent out in that first round were accepted for publication. And this was just under two years ago. I take it as nothing less than a conversation. A broad, cross-national, interstitial exchange that I am grateful to be part of.

I still carry on in much the same way.

JS: My earliest publications were in Pottersfield Portfolio and The Antigonish Review. I remember how thrilled I was to get those first acceptances after a slew of inevitable rejections—and how tremendously encouraging it was for me to receive that sort of validation. That feeling hasn’t diminished with time, and I hope that it won’t. I don’t ever want to reach a point where I’m not a little bit surprised, and a lot delighted, by the idea that there are people out there reading and connecting with my work.

SH: I’m grateful to the mags. I edited one for six years, a long time ago, so I know the work is hard and mostly unremunerative. I should thank the editors, associate editors, readers, proofreaders, graphic designers, and printers more often than I do.

What non-writing things have you done that have helped contribute to your development as a poet? (Eg. editing a journal, doing readings, attending conferences, being in a band…)

CL: Man, this is a good one. I often joke that my CV lacks focus and that life is too short for such business anyway. It’s true for me, though. I’ll give you a few examples. I have produced across many genres: dance, theatre, photography, music, writing, and others. Much of this has been part of my nearly two decades in community engagement, which has created in me a multi-modal soundscape. How this connects with poetry isn’t necessarily essential or contained but I often use a lot of persona in my poems, multiple voices, sometimes in the same poem. I’d like to think that I learned from these rich histories, how to be authentic to the experience of the act of the poem. And I don’t mean that there needs to be an autobiographical insistence. For me, the trueness of a subject in any given moment can shift dramatically depending on my presence, my attention to it. So feel that I always want to find the true iteration of the poem in that moment. This is very much like working in community. No two days are ever the same.

I also spent four summers as a support person for youth and children with disabilities and this helped me expand my capacity for deep listening. I’d like to think that I offer myself over to writing poetry in this way. I listen for its want, its yearning, its lack and then let it take me wherever: it’s a different kind of trust that I don’t often experience in real life interactions.

SH: Learning to play and busk a lot of songs, and trying to write my own, when I was in my teens and early twenties; travelling and working in Asia in my mid-twenties; editing a literary magazine; submitting to the mentorship of elders who sometimes told me cruel truths; memorizing poems; teaching myself other languages and translating poems from them; failing often and trying to figure out why instead of telling myself and others that the failure was in the reader, not me; walking thousands of kilometres over the course of about twelve years with a good, silent friend, my dog Isla, who is now gone.

ST: I prepare tax returns. I know how to pay attention and how to be responsible to my work. I know I can be successful and it has nothing to do with poetry. I think knowing this makes me better at what I do, if what I’m doing, is going to be of any value.

JS: The most significant thing I’ve done that’s contributed to my development as a poet is to read widely. It’s easy to keep discovering new writers, to keep falling in love with new epochs and styles. There’s so much out there and, from the perspective of a writer interested in language and how to make meaning in the world, it’s all good.