NPM22 Blog: Creating Intimacy Onstage by Charlie Petch

Effective performers have a talent for making the audience feel seen. They say the things you’d only think, and never speak. They somehow gain your trust from the stage, in front of a room full of people. As poets, how do you create intimacy on the stage? What are the elements of performance, of pacing, of emoting energy that will help your audience feel at ease in your presence? To have them feel open to your message, even on your side when you show your fears? My favourite nights will always end with someone telling me my poetry brought something out of them, that they trusted me enough to feel that in a public space. Poetry really is the language of intimacy, and creating an atmosphere of togetherness, of necessity for their presence, will only enhance the experience.

When I’m asked who my favourite live performer is, I first recall the emotion of being in that audience. The feeling I got while surrounded by thousands of other audience members, but the way he performed, it felt like we were in his living room. It was Tom Waits on his “Alice” and “Bloodmoney” tour. I’m going to guess it was 2003, and it was at the Hummingbird Centre in Toronto/Tkaronto. Looking now at the capacity (and it was filled) means there was almost 3,500 people there. But in my recollection? It was just me, my friends, Tom, and a couple of other musicians onstage. Like we were just around the corner from his apartment. Like we could have a drink after and laugh and maybe he’d want to jam. I was immediately obsessed with the idea that maybe, someday, I could get to a level of performance that felt that intimate to no matter the size of my audience.

When you see your goal, you take some notes; how did Tom Waits make me feel like that? First of all, he was very in the moment. Spoke about something that happened that day, honed in on a few people who were reacting in the audience, asked them direct questions, responded to them in a way that felt totally unrehearsed. He let the audience dictate the randomness he created. Then let them feel they guided him back to the next song. I also remember the magic, how everything felt so unplanned but at the same time, it was also a hundred little behind-the-scenes steps to take one big one together. Plus the glitter confetti tosses that were so wry I bark-laughed from my miles-away seat and hoped he felt it.

In my own poetry sets, sometimes I let the room tell me the poems they want to hear. If there are poets performing before me, I see what the audience is responding to. Is it political poems? Poems about how creepy Lamas are? Are they in love with a love poem? I rework my set. Abandon my plan of how I get from one work to the other but trust that I can bridge the poems in the moment. I reference the poets who influenced my set that night, take their names down and mention them onstage with me to credit them with the gift of guidence. In doing this, I am showing them that I am present, that this is just their show, that they are a part of my set because they created the atmosphere I walked into.

Another lesson from Mr. Waits? How you get from one poem to another, is a whole other show that you can keep open. While I will practice a set, I also leave moments between poems to travel with the audience. If I have a 20 minute set, maybe 5 of those are purely banter. I time my thank you to the host, the organization, my fellow readers, look at my notes to mention specific things I liked about their poems. Maybe I’m in the city for the first time so I tell people where I went that day, where I had the best burger on my tour. It’s so amazing to hear about where you live from an outsider who is utterly charmed by the place, or faced the same things that keep you from feeling comfortable in your city. If you’re a funny person, be funny, if you’re not, be as unfunny as possible and that might get a laugh. Your audience does not have to laugh, but when they do, it’s another level of intimacy altogether.

Laughter creates a particular kind of intimacy. When I have laughed hard, a few things happen to my body and mindset. First, I am rendered almost helpless, gasping for air, my belly shown like a trusting puppy, I have just spat something out, cried a little joyful tear, and I am so grateful to whatever had me laugh that hard. We want to cuddle up to that laugh, to that joy, we are ready, and open in so many ways to whatever is said next, wherever our guide takes us. For myself, I like to drop messages into that laughter, because truly, this is when you have the best chance of changing someone’s mind, or increasing their perspective, of having them care about what you care about. My favourite place on earth is always, in bed with a partner, after making love, when we are laughing about something so ridiculous. To me that is more intimate than sex, it is the closest I get to anyone.

How can a poet invite each member of the audience to feel they are in an intimate connection with their words? Their performance? You can start with the most simple feat of connection; meeting the eyes of those in the audience. If you are in the audience, you know the poet appreciates your gaze back, also that they might seek it out again, so you pay attention in a way that could never be achieved by a poet keeping their head down, in their work, the microphone pointed at their ear. When I am in that ignored audience, I feel that I don’t need to be there, that I don’t matter to the reader, and so I can make a real decision about paying proper attention to the poet onstage. While some poems are so good; they can transcend that barrier, and have been written with enough pathways into the work that the audience will feel immersed. But imagine if you could do both, how much more enriching your own experience will be.

Another way to create intimacy with the audience is leaving silent moments within the reading of the poems. Each space should have an intention, are you holding space for laughter? For tears? For a deeper understanding of a line that might take a few seconds to really show its full intention? When we performers leave space for audience reaction, we are saying we expect it, we are asking for full attention, we are inviting them into an almost collaboration of energies. Meet their eyes in this silence, let them see you expect a reaction. If they are laughing in the space you left, wait for the laughter to just dip slightly in energy and do the next line. No matter the emotion you want them to have, they will have a reaction to a poem that has gaps for them to fill in. Even before you start the poem, create some space, take a second to just be, before you open your mouth. It says, “I need you to be ready”, “I expect you to listen”, or even “please be quiet and look up, I’m going to begin.” It takes confidence to start your work when you feel ready, it changes the power dynamic in the room to let them know you see them, and expect them to be as ready to receive the work, as you are to give it.

Not only do I belong to the school of “how did Tom Waits do that?” I also have trained with clowns. Say what you want about clowns being scary, but I’ve never felt so close to achieving the atmosphere Waits did. I now even see his performance as clown. His energy exchange onstage, the way he’d zero in on a reaction, and push it even harder, and the way that his energy not only reached those of us near the top deck, but past the walls, and out onto Front street. Clowns need the audience, they are in constant conversation with them, letting them direct the night, what the next physical theatre moment will look like, and how, through melodrama, a single wink sent out from the stage, can feel like someone knows your deepest secret, if done correctly. Theatre is another form of intimacy, but only when the 4th wall is down, because voyeurism isn’t intimacy, but rather the fetishization of intimacy. But like anyone who’s become the observer in a threesome can tell you, it doesn’t feel like intimacy if no one is looking at you, or asking you to be a part of the show.

As I gain skills as a performer, I also become aware that I have a responsibility to my audience. That I want to leave them in a good place at the end of my set. I do my set ups according to the emotional path I want the audience to take. While intimacy is something that is incredible to achieve from the stage, one should also realize there is a responsibility to also ensure that the audience are not left devastated. When you fly a plane, you want to land it safely and the same can be said for poetry sets where you know you’ll take them to immense heights, but also that you will keep their trust if you do a soft landing.

It’s been a strange past couple of years to feel that intimacy that musicians, performers and clowns can achieve. At first I didn’t know if I could do that over a webcam in my living room. The need never went away though, and I made sure that I was giving the same level of performance to those who attended the many Zoom and other platforms we’ve been touring virtually. Intimacy can be achieved online, because we so need it. I look at the webcam, send my emotion and energy through the airwaves, through to the street, to my whole block. I channel the feelings of the poem and get caught up in them myself. Sometimes I stay after, have a drink with the poets like I would normally. Accept that this is our reality. We never stopped needing connection, we just changed platforms.

So when you perform, do it past the microphone, past the walls behind the audience. Meet the eyes of those who are there to witness, see their willingness to be on board with you and offer them space in your poem to add their reactions to. Tom Waits rarely tours because he’d always prefer to do a little impromptu performance at Murphy’s Pub near his place in Queens, and just jam and try out songs. Like Tom, you can take what works with a small audience and make it clown-sized. There are so many little souls in these audiences that just need; for a moment to feel seen, to feel they are not alone, to have intimacy in a moment of vulnerability, to feel held by a poem, to trust a performer, even momentarily, with their deepest intimate thoughts.

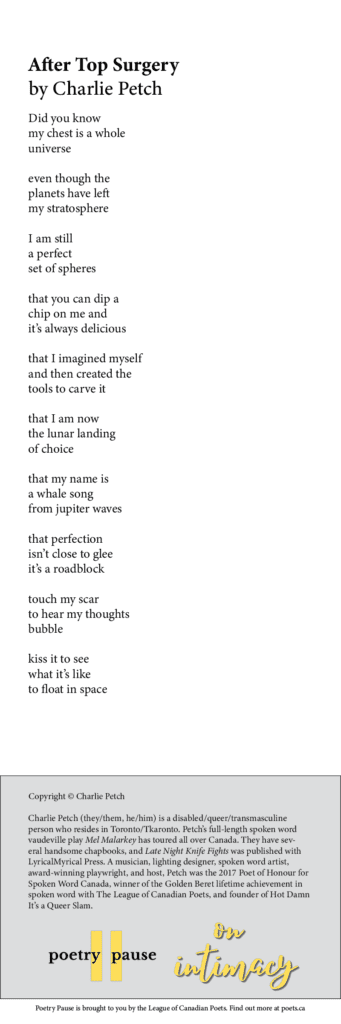

Charlie Petch (they/them, he/him) is a disabled/queer/transmasculine person who resides in Toronto/Tkaronto. Petch’s full-length spoken word vaudeville play Mel Malarkey has toured all over Canada. They have several handsome chapbooks, and Late Night Knife Fights was published with LyricalMyrical Press. A musician, lighting designer, spoken word artist, award-winning playwright, and host, Petch was the 2017 Poet of Honour for Spoken Word Canada, winner of the Golden Beret lifetime achievement in spoken word with The League of Canadian Poets, and founder of Hot Damn It’s a Queer Slam.