NPM22 Blog: Intimacy – So close that we are one by Johnny D Trinh

“sino así de este modo en que no soy ni eres,

tan cerca que tu mano sobre mi pecho es mía,

tan cerca que se cierran tus ojos con mi sueño.”

<that this: where I does not exist, nor you,

so close that your hand on my chest is my hand,

so close that your eyes close as I fall asleep.>

~Pablo Neruda, Sonnet XVII

What is it to touch someone so deeply that the membrane between bodies is dissolved into some unknown unity? Is it possible to lower our guards so completely, to enter a state of vulnerability, together, for a few fleeting moments? Can it be that close? Does it matter who we are or how we identify? Are we all entitled to consensual connections? Do people call this love?

Intimacy is measured by the space between ‘you’ and ‘I’. Intimacy is the space between ‘you’ and ‘I’. At least, this is how Stacy D’Erasmo defines Intimacy, while asking the question of “how do we, as writers, catch and reflect this on the page?” (D’Erasmo, 2013).

Poetry in any language, is a distillation of words to create finite images to convey a story. In many ways, I’d go as far as saying that poets spend our time acknowledging the truth within a story, with a goal to build an empathic connection between us, the readers, and the ‘characters’ within the poems. We use expositional sound and imagery as a framing device to present an intimate connection, to build an intimate connection. I’ll argue that Poetry is an articulation of Intimacy, a manifestation of relationships, captured in a permanent way so that readers and listeners will never forget that we existed, for however long ‘we’ exist.

Poetry taught me what intimacy looks like when it is dangerous, forbidden, and hidden. Poetry taught me what intimacy looks like when it is healthy, consensual, and liberating.

I’m still learning what it is to be a poet. Perhaps, more accurately, I’m still discovering what kind of poet I am. My entry point to this practice was through competitive slam poetry. Throughout my youth, I felt the imposition of strict gender norms, filial piety, and necessity of keeping secrets for survival. Desperately shy, relentlessly bullied, I did my utmost to lean into all the stereotypes of who I thought I needed to be… to be acceptable. It was so jarring, to live on this axis, where my existence was simultaneously scrutinized and invisible.

Though I wrote poetry in secret, for decades, it was never a form that I associated myself with. I spent the better part of 20 years professionally training in performance (singing, acting, dancing). I felt a deep seated need to be on stage, or on screen, to connect. Committing to be an artist, in itself was a defiance to the person I was pretending to be for so long. Unfortunately, after all that training… there were no [performance] opportunities of merit, there were no opportunities at all for many years. But then, in my first year of graduate school, a new friend, in an unfamiliar city, invited me to a spoken word event. It was early summer, hot, outdoors. I got up from our seats, walked across the plaza to the stage, and shared radical queer love stories through freeverse to a surprisingly welcoming audience in Regina, Saskatchewan.

Something shifted. I suddenly experienced storytelling and performing, uninhibited by the racialized standards of film, television, production… I was able to perform “me.” Only, it was more than being able to present myself holistically. It was always finding solidarity with other marginalized voices that can no longer bear the weight of the inequities they face. For the first time, I started to see more diverse faces stepping up to the mic. I wanted to be part of that.

I wanted to be part of something.

Intimacy is more than the space between people, the vulnerability required to connect, the sharing of one’s deeper sense of self;

Intimacy is a medicine for Loneliness.

Intimacy is the experience of traveling the distances between people, filling the spaces with every story we’ve ever heard.

I was recently performing at an online event, and a colleague commented on my work. It was the end of the reading, when participants graciously offer their acknowledgments of each other. This poet said, “It was so great having Johnny… and Identity poems.” It was a surreal moment, where I wasn’t sure if I was being compartmentalized, or celebrated. Perhaps both? I didn’t take offense to it, instead it allowed me to reflect back on my body of work and ask, “Is this how people hear me?” Does this lens then galvanize or erode the relationship I want to forge with the audience?

The unfortunate answers are, “yes, no, both, and neither.” Audiences are only able to communicate their consent by attending a performance, or agreeing to hear/read your work. Their consent means entering into a finite relationship where they will receive a poet’s work. But in that moment, when faced with the responsibility of holding an audience, while simultaneously being witnessed by an audience, that is one of the most intimate connections one can make.

I think that’s why my work relies more on situational episodic storytelling. Especially from my theatre practice, I am most comfortable creating scenarios that are time, and site specific, often framing a linear narrative through the eyes of a protagonist. My work reads like a monologue, and monologues exist to deepen relationships. Monologues provide exposition of the deepest thoughts of a character, or the truth that one feels the urgency to speak while facing barriers to speak it. My very first chapbook was titled, “I… You… Because… Repeat.” My graduate thesis project was titled, “#itscomplicated.”

In my work, common stylistic motifs include relying more on tonal sound, alliteration, assonance, and rhythm. I often use images pulled from the physical environment of a piece, though I would challenge that these fit the definition of metaphor.

It’s no coincidence that much of my recent work incorporates sex, sexuality, and food. I am deeply interested in the use of these to evoke memory, empathy, and associations with audiences. So often, especially within racialized communities, there is an initial observation made on food being a connection to one’s culture and identity. This implies that there is a risk of losing one’s identity and culture without it, that this connection is vital to knowing who we are, and how we connect. What connection could be deeper than exploring all the ways we consume each other, and take each other beyond the surface of our skin?

My research would be defined as autoethnographic, an examination of the cultural meanings of one’s own story, the the telling of one’s own story. My poetry could also be described as autobiographical, like many contemporary spoken word poets, rooted in knowledge of lived experience.

When performing my work, I apply all my theatre training, asking myself, “Who am I talking to? What do I want? Why now? Why would they stay to listen?” My early work was often directed at general audiences, “society as a whole”, white communities. My underlying message was, “We are here. We exist. We are in this together.” But as I learned more about the Spoken Word community, I realized that even here, there were proportionally less poets that looked like me, sounded like me. People generally don’t show up when unwelcome. You can’t invite the people you don’t speak to. I began focusing my work more on speaking to the people I wanted to listen to. “We, who share this story… I want to hear how you tell it.”

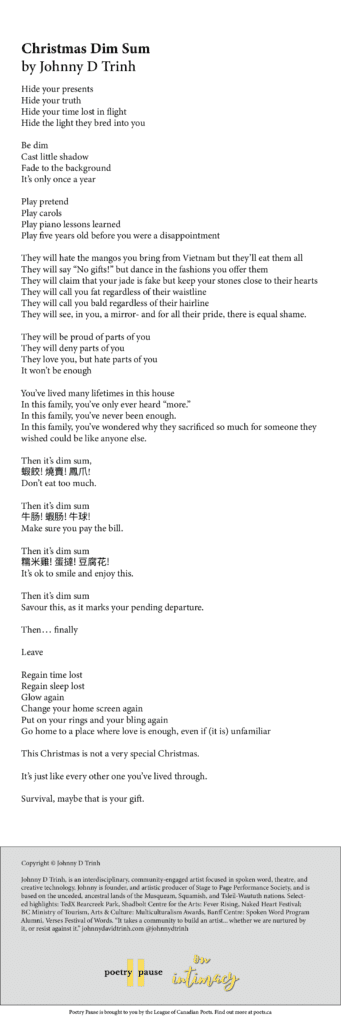

For National Poetry Month, I’m sharing my poem, “Christmas Dim Sum.” I think that it is one of my most intimate poems. It exemplifies everything I’ve discussed thus far, and it continues to evolve… becoming more of what it needs to be. In the poem, I depict an inner dialogue of an estranged someone, “coming home for the holidays.” I wanted to capture the process a person may take when they diminish themselves to appease a difficult circumstance, and the importance of knowing that decompression afterwards is possible. I feel the poem itself has a universal relatability in terms of experiencing the tension points within a familial relationship. I added a list of Chinese Dim Sum dishes… with the intention that they are read as if by a dim sum cart lady, calling items in a busy restaurant. This specificity also is a direct dialogue with Asian-identified audiences. The poem itself captures intimate relationships in public and private spaces and demonstrates a movement through time.

Intimacy is often associated with romantic love, or some form of sexual engagement. For my work, those themes are present, but not limited to them. I think of intimacy, at any given time, as either a consent or an invitation. It is not only the “truth” I’m telling, but the depth of that truth, and how far I’m willing to bring someone. There is nothing deeper than the family I continually suppress, bury, separate from my daily lived experience.

I spent so many of my formative years, consuming so many fairytale narratives of “it gets better.” I was a desperate zealot, faithless but praying for love. I learned that it does, indeed, get better. But “better” requires a great deal of time, effort, and vulnerability. Pablo Neruda’s Sonnet XVII is beautifully crafted. It speaks to an intensity of love. I had always associated it with romantic love, contextualized by its placement in Neruda’s series of sonnets. “I love you like this because I don’t know any other way to love.” An earlier line from Sonnet XVII struck me, because my nuclear family, my parents have said these things to me. They said they knew me so deeply that we were the same person. I extrapolate this meaning, through a reframing. I began to recognize that their collectivist identity, and all the filial piety, culminated in this view that we were/are one. And yet, sometimes the family we are unable to choose, are rooted in versions of ourselves that don’t feel true… but are still undeniable. Replace family with community. Replace community with audience. Replace audience with relationship(s).

For me, poetry is a way to build relationships that I intentionally choose. Within that consent, we adjust, and reveal, and resist against an isolating loneliness. Intimacy is the space between you and I, and as our story exists within that space. We connect to form a unity, where we can see how we retain ourselves.

Reference:

D’Erasmo, Stacy. The Arts of Intimacy: The Space Between. Minneapolis, Graywolf Press, 2013.

Johnny D Trinh is an interdisciplinary, community-engaged artist focused in spoken word, theatre, and creative technology. Johnny is founder, and artistic producer of Stage to Page Performance Society, and is based on the unceded, ancestral lands of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh nations. Selected highlights: TedX Bearcreek Park, Shadbolt Centre for the Arts: Fever Rising, Naked Heart Festival; BC Ministry of Tourism, Arts & Culture: Multiculturalism Awards, Banff Centre: Spoken Word Program Alumni, Verses Festival of Words. “It takes a community to build an artist… whether we are nurtured by it, or resist against it.” johnnydavidtrinh.com @johnnydtrinh