NPM22 Blog: I’m not an expert in intimacy and neither are you by Tyler Pennock

I’m not an expert in

intimacy and

neither are you

by Tyler Pennock

Read this article and poem in magazine format

I used to think that definitive things were evil. That an exact definition, a perfect example embedded the notion that nothing is good enough, and that no one would ever measure up. I felt that definitive answers were a trick to deny people the satisfaction of understanding.

When I taught my first poetry writing class, I realized that definitive things were not the problem. It was how people conceived of them that bothered me. This came largely from how often I had to convince poetry writers and poetry readers that their understanding of creativity was just fine. That the way they write, speak, see things can be beautiful to others, that there is no point in measuring themselves against what was done before. Or rather, what others claim has been done before. There are always unaccounted examples, unconsidered poems outside a person’s definition of great poetry.

Ten years ago, my friend Lee told me that poetry is a moment, a picture, distilled. Since then, I’ve grown to understand this a little better, in that it rarely matters what lens you use – much of the work is in where you point it.

One aspect of poetry that I like is the practice of pointing the lens at unusual places.

Places like me.

The dramatic irony in this?

An adoptee writing about intimacy. It’s not an irony I disagree with. There is something there. Like you, I’m curious to see how these words will play needle worker with familiar fabrics.

Somewhere deep inside that first (missing) connection lies a twist, a hidden detail, a deliberate imperfection in the final product of me that I too, am looking for. Perhaps that something might give you a fresh look, a renewed perception to vicariously ponder, as I retrace my world through relationships, knots on a line I trail behind me; or ahead.

I.

: closeness

If understanding is another body, then intimacy is the space between you. Like any geography, the features are unique to the climate, the temperature, and ways that space is inhabited. In this, we can imagine the closeness between two people as the growth after a wildfire. The first few touches like birch trees, goose bumps and reaching hairs the nutrients, begging to inhabit something again.

Whatever the cause, something

Grasses

Lichen

Fungi

Alders

Chir pine

Phytoplankton

Ctenopelta porifera

Lepetodrilus tevnianus

something will

inhabit

desolate spaces.

When my best friend Ian died in his sleep, I called my Ex. He wasn’t someone I would ever turn to, nor trust to soothe or calm me. But I was a squirrel in a conflagration; every reassuring memory, every soothing place was a flame, my destruction total, and I was darting between embers. I doubt I even said anything– and it’s possible that all he heard was sobbing, and Ian’s name.

This was because Ian had grown into me; so much of me was intertwined with his constant presence that almost every strength I developed involved him. That shock took weeks to move through me, and afterward I endured months of ebbing pain.

When Brick Books emailed me to ask if I would attend the printing of Bones, I called Ian to remind him that we’d planned this moment together. The immediate switch to voicemail cracked open my recovery, taking me back to his death. Comfort, safety, and strength were such essential features of our friendship that as I reconciled with the loss, the comfort that followed slowly pushed out the pain, and memory of his death; While growing out of Ian’s orbit, my mind struggled to hold pieces of him exactly as I remembered them, including the Facebook message that relayed his passing.

Another close friend had died months earlier, and his partner, Virginia told me that she feared she would forget what he looked like. She acknowledged that it was likely I couldn’t understand that feeling, but figured I would write that into something anyway, and left it there – between us. I wrote Fire in response, a piece on death and memory as part of Skin Hunger, a project for the Toronto International Festival of Authors:

“I know that what my eyes and my skin miss, my mind and memory will recall. And when you become a fog my mind can’t give description to, I know my skin’s hunger will lend ink to the blank page it’s desperately trying to colour. I don’t fear losing you completely because some part of me will always remember.

And that’s ok.

Even in memory,

Relationships are fire – they must be fed.”

But here I don’t see fire as a necessary constant– a lighthouse in the dark, because if you keep a fire going forever, you’ll eventually forget how to build it. The closeness of a relationship doesn’t exist solely in how long it survives, but in how often it renews itself after destructive events.

II.

: familiarity

The tap-clicking of a dog’s nails on the tiled floor in the morning, the soft, deliberate pressure of four paws moving toward you from the foot of your bed, or that first long, audible breath coming from your partner minutes before sunrise. These things grow into you like shoots through earth, insistence matched by an easing in the dirt around them; repetition growing into the space you leave for them.

I came to Toronto in 1997 to be untethered. To be somewhere without familiar features or memories, no cardinal points to walk between. I wanted new, and I wanted to arrive empty. This was visible through an inventory of the things I brought with me: a stuffed bear, a torn T-shirt, a few pairs of underwear, 23 dollars in change, a writing book, and Irvine Welsh’s Ecstasy. The writing book was empty, the T-shirt was a favorite possession of my boyfriend (who didn’t yet know I was in Toronto), the change and the underwear were stolen, and the book was the only thing I couldn’t sell before leaving. Almost everything I carried was memorable for the disconnection it represented.

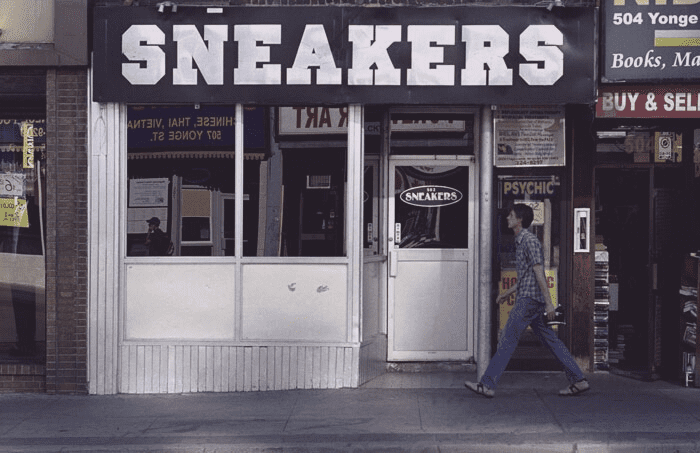

In a new city –unfastened– I wandered. I walked around or two days before I found Covenant House. From there I wandered for another few days before I found Church and Wellesley, 10 days before I saw the inner harbour, and 2 months before I found my first home, Sneakers. It started as a prominent feature in a growing cartography of Queer bars, youth outreach centers, coffee shops and parks, and then grew into routine. Grew into me.

If you could shut out the green walls and smell of old beer, wash out the jukeboxes and the pool tables, the ceramic tile floors, and the bottles against mirrored walls, and watch us- you’d see a mall, a park, a friends’ basement after school. If you forgot assumptions about bars, and sex work, and youth homelessness, you’d glimpse a freedom. Between tricks we too, experienced friendships, attractions, love, coming-of-age moments, and many significant firsts.

Sneakers was where I met my first trick, and also where I met my closest friend.

In a bar where touch is the commodity, a lack of intimacy is agency – an enforceable boundary, an assumption rolled and kneaded into everything. If you witnessed a friend, partner, or even a john touching us, you knew that was negotiated, and we managed the mystery of that allowance to our advantage. If you saw hand on us, you would want that, too. The longer you witnessed it…

Ian never propositioned me.

I let him hold me. Visibly.

Often.

Ian grew into a space reserved for trusted friends, a space later inhabited by some of my partners – reserved for people who made no demands, no claim.

I am not and never will be property.

I’ve written many poems about this – my disgust of ownership. One of my partners (the subject of a poem in Glad Day’s Smut Peddlers, B.) – was legendary for not letting johns touch him in the bar. More than once I heard him scream this at men in Sneakers. This insistence was one of many things we shared when meeting. But our short-lived relationship was as predictable as the painfully obvious, years-long attraction we had – we couldn’t mutually negotiate intimacy. (I left him for his ex, who was far more forward, and I needed that.)

Another poem in Bones was based on a man who flaunted his presumed ownership of us regularly. He would hold his arm around boys all the time, some of whom were frequently his employees. He weaponized the flex, the use of buying drinks as an opener. In the poem, his eczema spots and belly were a stand-in for his face, the excess of both allergens and appetite obscuring any real relationship or understanding. In that scene, the protagonist was not puking over the sex act, but for the damaging influence of the power that john maintained.

Any harsh words or representation of that world comes not from a disdain for sex work, but for the people who didn’t respect our boundaries, our agency.

III.

: understanding

When a person you love disappears into a thickening whiteness, you search. Not for them, but for their impact on you – every memory, touch, or emotion they triggered, tracing the trail they’ve worn in you over time.

Ian and I shared a love of Clive Barker. Once I told him about my favorite moment from Imajica, where a main character (Pie ‘oh’ Pah) watches his love through a heavy scrim of falling snow. (It’s the reason why I love watching the first snowfall of a season, and why I want to experience a winter in New York.) When I spoke of it then, I focused on the intensity and longevity of one’s love for another through interference. I thought that the intensity of a feeling enabled a lasting connection.

I realize now that I was mistaken. What is beautiful in that moment is the way in which Pie increasingly had to rely on memory to fill what his eyes were losing grasp of. That his vision adapted to the snowflakes falling through the space between them.

That conversation with Ian, and the many that followed it were an opening, a vulnerability that I needed – that everyone needs, and will find a way to foster.

My favorite feature of Sneakers was that it was an unlikely home. A home where thousands of moments like these were held – precious because they existed, defiantly where many thought impossible. Equally impossible was how it harboured Ian – bouncer, protector, and close friend to many.

We, the street youth and prostitutes of downtown Toronto, were not watched carefully by parents or concerned neighbours or teachers, but we were watched. And while the advice we sought, the conversations we held, and the relationships we formed were in the company of men who paid for it, for many of us, it was safer than home.

What grew out of the destruction of our former lives became the strengths we used to negotiate the world thereafter. For me (indeed, for many), Ian was a very large promontory that the web of our lives depended on for decades.

IV.

If intimacy were a carpet web, then shared moments would be the branches and walls it holds on to. Each new line is a repetition, the weaver – or weavers, walking and re-walking familiar paths between anchors, trailing silk, strengthening the connections with every passing.

In this, change is a fallen branch, a storm, or a wildfire, and intimacy is the strength of your desire for connection, reforming the lines repeatedly, in ever-changing environments.

intimacy isn’t a definite, discrete thing – it is a pattern

an instinct

as unique to the weaver

as the place they occupy –

keep weaving

About the Author

Tyler Pennock, author of Bones (2020), is a two-spirit adoptee from a Cree and Métis family in the Lesser Slave Lake region of Alberta. Tyler is a member of Sturgeon Lake Cree Nation. They graduated from Guelph University’s Creative Writing MFA program in 2013, and currently live in Toronto. Their second book, Blood will be published by Brick Books in the Fall of 2022. www.tylerpennock.ca

A Poem On Intimacy by Tyler Pennock