When Poems Are Rooms

by Onjana Yawnghwe

for National Poetry Month, April 2020

Poems are places for the mind, and as places mark you, so does poetry. Yet the mind is currently occupied, table for one. If the mind is a room, there would be no floor space, the shelves crowded with pictures of strangers, loose wires, and odd knick-knacks. Digital footage of celebrities dancing and talking to a camera would be projected onto the walls. In this age of compression, you lack perspective in distance and time; the speed you desire to go is not the speed with which you move. No one has reminded human bodies of this, because the heart pumps at the same rate it always does. Technology outpaces us all.

In your spare time, you enjoy reading dystopian novels and especially like the beginning of zombie movies, before people actually start dying. On a related note, it is with complete surprise that the year has turned out this way. Did anyone know we were going to end up in this nightmarish plot? Pandemic gets us going. Narratives are born every day, and they make their own cries in an anxious world. Stories spread by tweets and posts on social media begin to overrun your mind. You wonder if there will be a time to panic, and if that time will come soon. When the panic comes, you realize that it hasn’t come soon enough.

You have difficulty being alone with yourself. There are only so many things that you can consume before you get indigestion, spiritually and emotionally speaking. You are reading a lot of poetry, perhaps to counter the attention-deficit behaviors of social media. Because sometimes you compulsively look on your phone every fifteen minutes, refreshing the feed, wanting new content, craving new takes. You sometimes find yourself thinking too much in memes. The word meme is rather difficult to explain. The little screen in your hand gives you the illusion of being noticed.

As a child, you were drawn to difficult things, and so when the school teacher asks the grade five class to memorize two poems, you choose one about death as a gentleman in a carriage by Emily Dickinson, and another by Robert Frost about the explicit ways in which the world ends. The poets are white and don’t look like you. Yet you like their particular solemn music, the paradoxical and joyous way in which the words collide. You think that by repeating the lines over and over, you will eventually come to understand them. Due to some strange power of their alchemy, you still remember every line of the poems to this day.

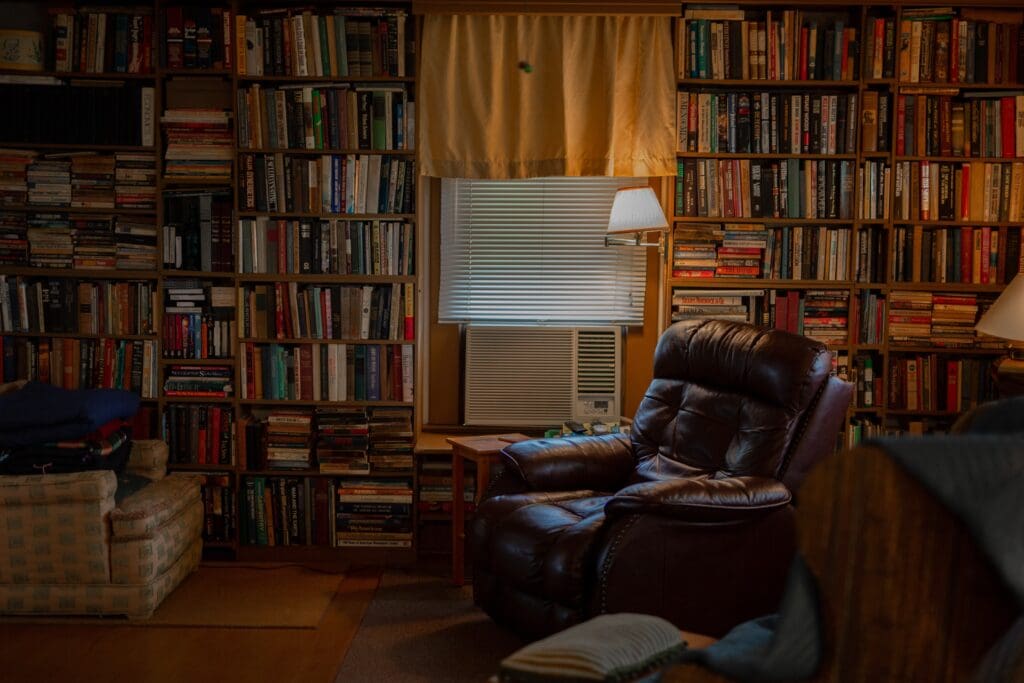

So what if you have a conflicted and ambivalent relationship with English? You lost the language you were born with and didn’t know where it went. You assume that if someone were to break open the shadowed corners of your brain they would find it dusty on a shelf somewhere. You were always a hanger-on to language, glimpsing the party from a gap in the door. So when you fell in love with poetry, your affections extended to the old world, like an Edwardian young lady on a Grand Tour. Rimbaud and Baudelaire in France, Pessoa in Portugal, Neruda in Spain. When poets become buildings, they would be grand and intricate edifices, with rooms containing carved benches and small, locked cupboards. Designed to seduce, promising a sweet time.

When you were a child, it didn’t occur to you that brown people wrote poetry. Eventually you learn of that other world running beside this one, where the same words are used, but in an order that fights and resists. Instead of longing, a reframing. While examining of the architecture of it all, you learn of basements and attics, because that is where the forgotten hide, the ones who weren’t allowed to write. If poetry was an ocean or a beautifully designed building, you would get surely lost. Some places make you feel welcome, while others push you out while trying to entice you. A revelation, a conversion, a connection. The poem: a voice reaching out. You sit here. You force myself to be still in your seclusion, cornered by distraction. You, in a room, with a poem.

Poetry encourages being alone. To be extreme about it, poetry is a one-room cabin in the middle of nowhere with only one window you can look out. Poetry is when you close your eyes at night, and before you drop into sleep, you see stars. Poetry is a mind illuminated by the light of the moon. Poetry is inwardness in the notation of a blank page. Pauses remind you of music. You can’t help but resist this, not wanting to stop moving, not wanting to stay still or concentrate. There is a tiny whining creature inside you which wheedles away at all your best intentions.

You force yourself to sit, swearing loudly at yourself. You sit. You make yourself a large cup of coffee and find yourself mixing metaphors into it instead of sugar. Remember that the cabin has one window, and not even a door. Or perhaps poetry is a body of dark water that you see your reflection in, like that ancient, beautiful youth who sat by a pond.

And oh, you dive right in. And gods, the water – the water is lovely and warm, and you’ve forgotten how buoyant your whole body gets, how it effortlessly floats, how you stroke and cut through the water and find yourself far away from where you started, and how you can just lay there on your back, the fat of your thighs and hips finally doing you good, and you let yourself drift wherever the current takes you.

The ocean you find yourself in is oddly familiar, and that is the strange thing about poetry, how it is so solitary, but the realities spoken by the poem are shared by many. You have isolated yourself but can’t help but feel connected to the entire world, and not just the world, but across time, as if you were a time traveler who ends up in an ocean, your feet grazing but never touching bottom.

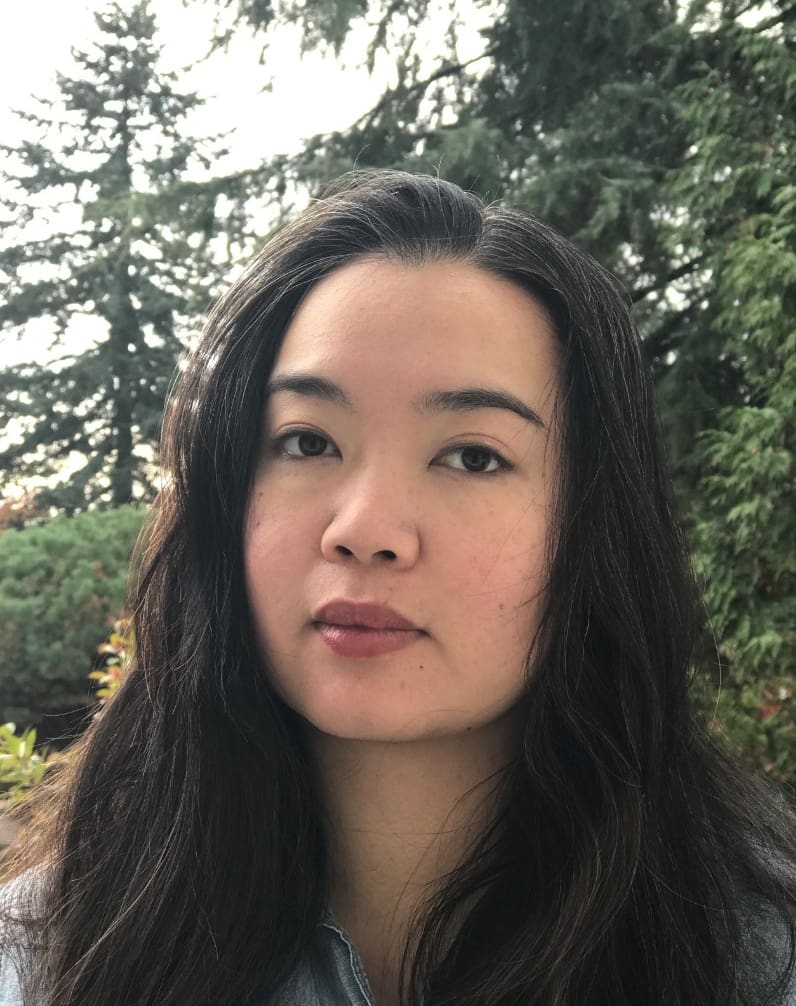

Onjana Yawnghwe was born in Thailand but is a part of the Shan people from Burma. She grew up in Vancouver, and received a MA in English literature. Her poems have been featured in numerous anthologies and journals, including The Best Canadian Poetry in English 2011, 4 Poets, CV2, Room, and The New Quarterly. Onjana produced a hand-made chapbook with JackPine Press called The Imaginary Lives of Buster Keaton. She was a co-founder of Fish Magic Press, a micro press specializing in limited-run, hand-made chapbooks, and was a co-editor of Xerography, a little literary journal. Her first poetry book, Fragments, Desire, was published by Oolichan Books in 2017, and was nominated for the 2018 Dorothy Livesay Prize. Her second book of poetry, The Small Way, was published with Caitlin Press in 2018. She is currently working on a graphic novel about Burma (Myanmar).

Onjana has taught English as a second language, and worked in office administration at non-profits for many years. She currently works as a nurse in mental health. Aside from writing, Onjana also hosted a podcast and blog called “The Alaskan Riviera” about the 1990’s television show Northern Exposure. She lives in Coquitlam, BC. www.onjana.com