Learning from Pier Giorgio Di Cicco (1949-2019)

Introduction by Diana Manole

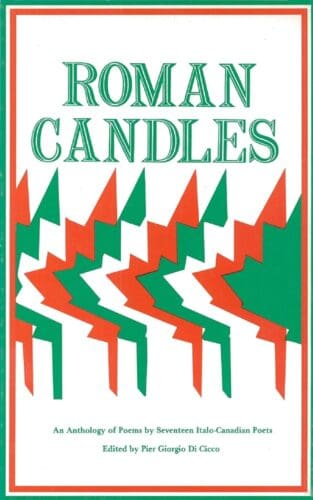

Pier Giorgio Di Cicco’s poems have always brought me the enjoyment of spiritual grace strongly grounded in sociopolitical and cultural activism. I’ve taught his work in all my Canadian Literature courses, while also emphasizing his contribution to helping Canadians become aware of the very existence and wealth of immigrants’ literature through the 1978 edited collection Roman Candles: An Anthology of Poems by Seventeen Italo-Canadian Poets.

Pier Giorgio Di Cicco’s poems have always brought me the enjoyment of spiritual grace strongly grounded in sociopolitical and cultural activism. I’ve taught his work in all my Canadian Literature courses, while also emphasizing his contribution to helping Canadians become aware of the very existence and wealth of immigrants’ literature through the 1978 edited collection Roman Candles: An Anthology of Poems by Seventeen Italo-Canadian Poets.

When the University of Guelph’s School of English and Theatre Studies appointed me in the fall of 2019 to teach ENGL*3060 Intermediate Poetry Writing Workshop, I strongly felt that emerging poets could learn from WishipediA (Mansfield Press, 2018), his latest and now, tragically, his last book. One of the assignments required students to discuss two texts of their choice from this collection and write one poem in response.

Maggie’s essay and poem have especially given me the feeling that she truly “got” Di Cicco’s message. She is comfortable crossing time, cultures, and generational barriers with academic expertise but with tongue-in-cheek poetic irony, respectful but not submissive. I hope you’ll agree that a student’s mindful academic and creative responses might be one of the most compelling ways to honour a writer’s memory.

May Pier Giorgio Di Cicco rest in peace and may(be) continue his writings in Neverland!

Intertextuality and the Construction of Neverland in Pier Giorgio Di Cicco’s WishipediA

by Margaret Lehman

Pier Giorgio Di Cicco’s collection of poetry titled WishipediA relies on intertextuality to explore complex concepts of time and space. By doing this, Di Cicco is able to construct an alternate vision of J. M. Barrie’s mythical island Neverland – one that exists in an era of constant technological advancement and consumerism. Through an analysis of the poems, “Get Dressed” (30) and “Can I Rewrite DNA?” (53), I argue that Di Cicco’s version of Neverland is one of warning: while technology connects the world, it simultaneously disembodies it.

Intertextuality suggests that texts are not “separate entities but [rather] connected discourse” (Lundin 210). Every work is therefore inspired by another, drawing upon old texts to create entirely new works. Di Cicco relies on intertextuality, explicitly referencing two other texts in his poem “Get Dressed” (30). The first occurrence is an altered quote from T. S. Eliot’s “Burnt Norton” (1936): “Time present is / Time future and time future is / Time past” (30). The original reads, “Time present and time past / Are both perhaps present in time future, / And time future contained in time past” (Eliot). The use and change of Eliot’s concept of time establishes the abstract way in which Di Cicco perceives and structures technological dimensions. “Get Dressed” tells its readers that they “have a cyber-suit” – that they can “pick a year” and travel in time (30). It even goes as far as to say that “Einstein’s injunctions against speed of light / Travel have collapsed” (30). By reimagining the world in this way, Di Cicco deconstructs the linear, chronological order of time.

The second instance of intertextuality in “Get Dressed” is the reference to J. M. Barrie’s fictional world: “Together, you [and your aunt] create Neverland” (30). This reference suggests several things. First, Neverland is connected to the personal. The imaginary reader, “you,” and their aunt creates Neverland, no other character is involved. Therefore, it is possible that multiple Neverlands exist. Second, Neverland is built when the characters time travel or use their cyber-suits to “reflect” on the past: “It’s your hologram. Sadly, your aunt / Cooked up her own, and she reflected on / 1939, though you weren’t born until 1982” (30). Barrie’s Neverland is replaced by the alternate version Di Cicco envisions. Finally, Neverland is a space or place that is not here. In order to time travel, use the cyber-suits, or experience the “cold wash light of the web” (30), the characters must leave their physical body behind. In this way, Di Cicco’s construction of Neverland resembles that of Barrie – a fantastical location that offers its visitors an escape from their reality.

Di Cicco continues with his reimagining of Neverland in the poem, “Can I rewrite DNA?” (53). He begins by telling his reader(s) that they are in a multiplayer-game, attempting to rewrite their DNA in order to find belonging. He uses scientific language and imagery to construct this space: “change the cells by mutation, by / Cybernetic loops of good intention”, “modify behaviour”, “reorientation of black holes” (53). Once the reader, “you,” seems to have satisfied the players in the game, Di Cicco comments:

“Tick Tock, Tick Tock.” Here comes Captain Hook always

One step ahead of the crocodile. Are you the

Timekeeper?

Are you the Pan?

Are you the Hook?

This intertextual reference to Peter Pan and Neverland is used to question the readers on their role and intentions in the game. Are they the crocodile who is intent on eating the villain? Are they Peter Pan, outsmarting and playing with Captain Hook? Or are they Hook himself intent on destroying Pan? The questions regarding identity in relation to Neverland characters further constructs the “game” as Neverland. Di Cicco starts the poem by stating “Whenever you choose not to belong” (53), instantly pushing forth the imagery of Peter Pan and the Lost Boys – those who are lost, who do not know where they belong, who do not want to belong. The consequence of rewriting the DNA, as suggested by the end of the poem, involves the introduction of the Timekeeper, Pan, and Hook – characters who exist primarily within the borders of Neverland. Di Cicco’s reconstruction in relation to technological spaces and the possibility of rewriting the DNA in order to find belonging is one that not only provides an escape from reality, but also foretells the consequences of such actions.

Anne Lundin provides further analysis of the value of intertextuality, stating that the “examination of alternative versions suggests the way stories are altered as cultural devices, the need to know a wide variety of versions for multicultural storytelling and collection-building, and the sheer universality of certain stories across spacious continents” (211). While Lundin’s approach often refers to a geographical expansiveness (e.g., stories that cross continents and cultures), the crossing of temporal boundaries is perhaps even more so at the forefront in Di Cicco’s poems. His construction of an alternate Neverland is fuelled by the future, by technological advancements, and the ways in which humans interact with this technology. Therefore, this fantastical place and space has not only crossed continents and cultures, but it has also endured and evolved through time.

It is also significant to note that the type of society in which Barrie wrote and produced his play, Peter Pan, or The Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up (1904), and imagined Neverland is one that has faded. In its place, there are societies and cultures that are interwoven with advancing science and technology. Di Cicco’s alternate version indicates that stories do not just cross geographical borders, but they can also cross time and cosmic barriers. The end result becomes a warning to anyone who will listen: while technology can be connect us all and provide an escape from our realities, it also has the power to disembody us.

Works Cited

Barrie, J. M. Peter Pan; or, the Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up or Peter and Wendy. Hodder &

Stoughton, 1911.

Di Cicco, Pier Giorgio. WishipediA. Toronto: Mansfield Press, 2018.

Eliot, T. S. “Burnt Norton.” Poeticous, 2019, www.poeticous.com/t-s-eliot/burnt-norton-from-

four-quartets. Accessed 2 December 2019.

Lundin, Anne. “Intertextuality in Children’s Literature.” Journal of Education for Library and

Information Science, vol. 39, no. 3, 1998, pp. 210-213.

Diana Manole is a Romanian-Canadian scholar, literary translator, and award-winning author of nine books of poetry and drama in her native Romania. Her poetry in English has been published in magazines and anthologies in Europe, the UK, the US, Mexico, South Africa, and Canada, and in the English-Romanian book B&W (Tracus Arte 2015). Holding a doctorate from the University of Toronto, Diana teaches academic and practical courses in theatre and performance, literature, and creative writing at universities in Southern Ontario.

Margaret Lehman is a Bachelor of Arts student at the University of Guelph, pursuing specializations in English Literature, History, and Creative Writing. As a poet, she is interested in exploring human and other-than-human relationships with the environment.