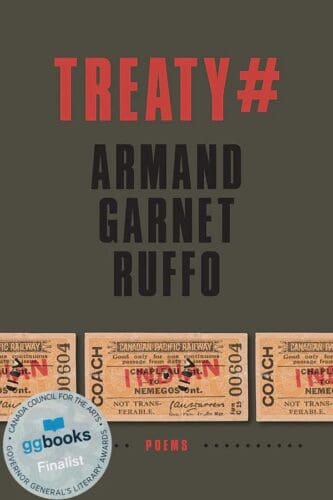

Review: Treaty # by Armand Garnet Ruffo

Reviewed by Marguerite Pigeon

Treaty # opens with a prose poem, “Impetus Ungainly,” in which Armand Garnet Ruffo manipulates language from a 1905 treaty between the British Crown and Ojibwe, Cree and members of other Indigenous groups in Ontario. The poem’s title hints, bitingly, at the treaty’s function. It was the legal body that enforced European interests, with zero long-term gain for Indigenous nations. But the poem refigures that body, acting on readers too, bringing us backwards and forwards through the treaty’s pompous, confusing (ungainly) wording. In this way, Garnet Ruffo flips the deadening anti-poetics of the original document, damning its status games while maintaining space for, and awareness of the fraught position of the Indigenous signatories.

Before I go on, I want to acknowledge my own position—I’m a white, Franco-Ontarian settler from the same Northern region where Garnet Ruffo’s Ojibwe community has always lived. This is relevant to this review because I have benefited directly from treaties that gave Europeans unfettered access to natural resources there. Like many French Canadians, my grandfather moved to my hometown, Blind River, in the 1930s, eager to gain from a sudden prosperity that actively excluded Indigenous participation.

From this context, I read “Impetus Ungainly” as signalling the overall poetics of Treaty #: this collection taps Garnet Ruffo’s personal experience, which is tinged by the ungainly language and exclusions of colonization, for poetic resources. Treaty # is a wide-ranging work that travels freely beyond a single subject, however. Garnet Ruffo tangles with feeling, connection, silence, responsibility, doubt, confusion and more—all in the name of taking the poetic reigns. The result is a delicate, personal book that is often about the writer’s complex relationship to poetry itself, and, more fundamentally, his opportunities for speech.

In ‘The Claim,’ Garnet Ruffo blends event (the bitter irony of a van doing rounds among homeless Indigenous people on a cold night), memory (wearing socks to bed in winter as a child), and present-day minutia (the narrator adjusting a thermostat) with a deeper remembrance of kin as the true warming presence. The poem culminates in anxious awareness that, for Indigenous people, communication with the distant past—the titular ‘claim’ to continuity—can be interrupted by colonialism: “I see ghosts of family through the curtains smiling/at me, in sunshine, in a forest, bathing in a small lake/holding all the warmth of summer, they are speaking/to me in a language I don’t understand.”

This disturbing interruption, like static on a phone line, returns elsewhere in the book, as Garnet Ruffo captures instances in which openings to speak of pain, loss or fury slip away. “Red is a Poem,” structured in water-like, cascading stanzas, explores the complexity of Indigenous experience, but begins and ends with the assertion that the perfect poem is “just out of reach,” while, in “Haliburton Highland Night,” the narrator, reflecting on a false claim that a particular area was never inhabited by Indigenous people, drives away, seething: “I keep my mouth shut.”

Indeed, Garnet Ruffo challenges the silencing impulse and willful blindness to Indigenous presence of settler culture. In the aching, ‘Why don’t you Write?’ the poet, addressing the recipient of a racist postcard, writes: “I could feel Lily’s ignorance enter the room/like absence, like cancer…” And in “Under Construction,” Garnet Ruffo demands that we notice who is left out of the picture in Group of Seven paintings: “Only landscapes allowed./ Not a bird or a bee./ Not you. Not me. Nothing.”

Elsewhere, Garnet Ruffo reflects on his own rich experience as a traveller, an established writer, a cousin, and a descendent. He dreams of revolution in Cuba; feels lonely touring a Paris graveyard; returns to Northern Ontario in “At my Great-Grandfather’s Cabin,” where a transcendent moment sparks under the cabin’s broken roof; and, in “Hidden Residential School Graveyard,” conveys, in near-spiritual stream of consciousness lines, the blistering pain of encountering those small graves. Treaty# lives with this pain, and with the tension between a full life and ongoing colonial silence. Garnet Ruffo’s generous collection shares the poetic resources of his experience.

Marguerite Pigeon writes poetry and fiction. Her first collection of poems, Inventory (Anvil 2009) was a finalist for the Gerald Lampert Award. She has also published two books of fiction. Her next publication, a book-length poem called The Endless Garment, about fashion and dress, will appear in 2021 with Wolsak & Wynn. Originally from Blind River, Northern Ontario, she lives and works in Vancouver.