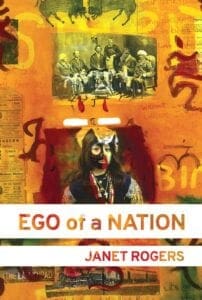

Review: Ego of a Nation by Janet Rogers

Reviewed by Miles Morrisseau

Janet Marie Rogers’ 7th book of poetry is her double album and it may become her classic. Rogers, who is Mohawk and Tuscarora, is a gifted poet and she has written the book that Canada needs to read in 2020. The year we see clearly: if Canadians wish to look honestly at their country they need to include the clear eyes of Janet Marie Rogers. Ego of a Nation also speaks specifically to her Indigenous relations and she does not whitewash her words.

Janet Marie Rogers’ 7th book of poetry is her double album and it may become her classic. Rogers, who is Mohawk and Tuscarora, is a gifted poet and she has written the book that Canada needs to read in 2020. The year we see clearly: if Canadians wish to look honestly at their country they need to include the clear eyes of Janet Marie Rogers. Ego of a Nation also speaks specifically to her Indigenous relations and she does not whitewash her words.

Ego of a Nation is the voice of an Indigenous woman living within a country built on the backs and the bones of Indigenous Peoples. The voice of the most marginalized, abused and murdered in Canada. The voice of someone who still believes in a higher human identity.

There are over 70 poems in Ego and the collection is bursting with hope, recrimination, joy, anger, sex and song. It is Rogers’ most ambitious work and like classic double albums such as Springsteen’s The River, The Rolling Stones’ Exile on Main Street or The Clash’s London Calling, the length allows for room to experiment and explore.

See the trailer for Ego of a Nation:

It arrives during the pandemic in which most of the world has been living in isolation and the code of social distancing is being enforced with authority and icy stares. Into this strange new world, Ego enters with a prayer to physical and spiritual contact. “Listen to Each Other Breathe” is for all of us who are reaching back to reclaim Indigenous practices and cultures and a world “we once recognized and had libraries of languages to describe.”

Rogers advocates a deeper connection that will awaken our “collective consciousness” and she reminds us to keep love and laughter in our prayers:

hold berries between your fingers

and remember

fun

love is silly

but we still love

There are heavy hard words as well, but she has room to move and there are pieces of joy and play and love and fun that lightly lift up like “Sunshine and Biscuits”. There is playful sexuality in pieces like “Show me yours” and more adventurous sexuality in the “Good Trade” with the lines:

I’ll wear your mask you wear mine so we can make love

to ourselves and each other

at the same time

Her responsibility as a writer is detailed in “Ash to Ink” and casts a critical eye to the national canon:

White Devils appear

in text with far too much forgiveness.

She takes on that greater responsibility to acknowledge the human family and the fact that we are in this together. It is reminiscent of Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed:

Remind the enemy

they have identity too

She continues to lift up and inspire throughout, and in many of the poems, Rogers is speaking to the Indigenous generation that is seeking out the secrets locked in their own stories and language. In “Level Ground” she encourages:

fear not

the excellence within us

love our colours

like we love the sky at sunset

The titular poem “Ego of a Nation” relates the tragic story of Colton Boushie, a young Cree Man who was killed by a White Man in rural Saskatchewan. The man who shot the unarmed 22-year old was found not guilty by a jury “exercising the ego of a nation without identity or foundation.”

the murdered man slumped over the wheel

of his vehicle upon lands once known as his

The ego is your sense of self-esteem of self-importance. Does the jury inflate that national sense of self which is based on an identity that does not acknowledge the Indigenous genocide in Canada? After all, it is not genocide if the killing is justified.

Rogers’ poem “Opiates” references the Marxian quote regarding religion as “The opium of the masses.” In this poem, Rogers brings the eye of a long time Vancouver resident who has witnessed, like everyone in that harbour city, Canada’s western front losing the war on opiates. She also writes from lived perspective and her sobriety is addressed more directly in “Blinking, Beating, Feeling”

I reached for the drugs

remembering they worked once

like permafrost under where

everything is buried and nothing grows

Violence against women and a world where “the bruises will fade” is addressed in “Measures of Masculine” which focuses a truthful perspective that I feel is directed at Indigenous men.

the inability

to love deeply

is rooted in

crisis of identity

Rogers is a talented spoken word artist and I can only imagine that her live readings channel Public Enemy’s Chuck D, with Rogers spitting verses like in “Spirit of Rage,” her fiery takedown of White Supremacists:

enraged from lies told to them

living false culture and religion

making us victims of white confusion

Rogers writes honestly about the challenges and the weakness within, “Who’s Who” connects the existential crisis of Indigenous Language loss with the breakdown of our family and community.

the soul of my language

wanders lost upon the lands

like a man who has died on foreign soil

with no family or protocols to carry him home

Ego of a Nation ends with a beginning. As if arising from a dream or falling into one, Rogers asks, “Where the Hell Am I?” as memories of loss and family far away arrive with the sun.

I am thinking about my territory

snow-buried and wind-ravaged

before first growth slashing and planting

the river that snakes through

a dark hue seen by hawks

Ego of a Nation is a long trip but it leads down so many rewarding roads and pathways. Tuck in and move slowly through it. Like a great double album, it will satisfy upon first pass and reveal more truth and grow in appreciation upon repeated returns.

Ego of a Nation will be available in Mid-May from the newly established Ojistoh Publishing

Janet Marie Rogers is a Mohawk/Tuscarora writer from the Six Nations band in southern Ontario. She was born in Vancouver, British Columbia and has been living on the traditional lands of the Coast Salish people (Victoria, British Columbia) since 1994. Janet works in the genres of poetry, spoken word performance poetry, video poetry and recorded poetry with music and script writing. Janet is a radio broadcaster, documentary producer and sound artist.

Janet Marie Rogers is a Mohawk/Tuscarora writer from the Six Nations band in southern Ontario. She was born in Vancouver, British Columbia and has been living on the traditional lands of the Coast Salish people (Victoria, British Columbia) since 1994. Janet works in the genres of poetry, spoken word performance poetry, video poetry and recorded poetry with music and script writing. Janet is a radio broadcaster, documentary producer and sound artist.

Miles Morrisseau is a Metis Writer living in the historic Metis community of Grand Rapids, MB. He has worked in Media and Communications for over 3 decades and served as editor for the top Indigenous publications such as Nativebeat, Aboriginal Voices Magazine and Indian Country Today as well as the National Native Affairs Broadcaster for CBC Radio during the Oka Crisis. He produced Buffalo Tracks with Evan Adams , the first Indigenous Talk/Variety Show for APTN and was Program Director for Streetz 104.7 the first commercial radio station by and for Indigenous youth. He continues to write essays and commentary on his blog NativeWritesNow. In 2020 he committed to invest more of his time into writing and reading poetry.

Miles Morrisseau is a Metis Writer living in the historic Metis community of Grand Rapids, MB. He has worked in Media and Communications for over 3 decades and served as editor for the top Indigenous publications such as Nativebeat, Aboriginal Voices Magazine and Indian Country Today as well as the National Native Affairs Broadcaster for CBC Radio during the Oka Crisis. He produced Buffalo Tracks with Evan Adams , the first Indigenous Talk/Variety Show for APTN and was Program Director for Streetz 104.7 the first commercial radio station by and for Indigenous youth. He continues to write essays and commentary on his blog NativeWritesNow. In 2020 he committed to invest more of his time into writing and reading poetry.