Shush, a review of Eleonore Schönmaier’s Field Guide to the Lost Flower of Crete | Louise Carson

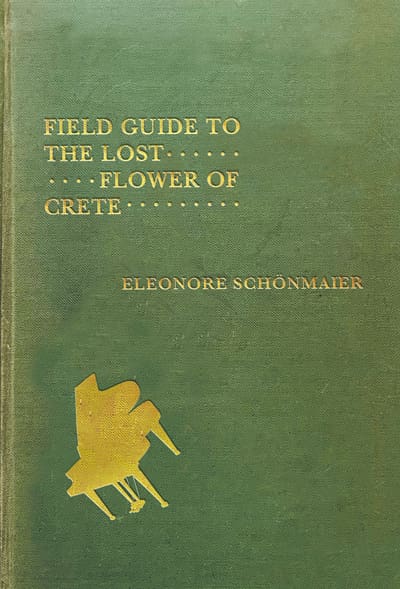

Field Guide to the Lost Flower of Crete

McGill-Queen’s University Press 2021

Part of the Hugh MacLennan Poetry Series (number 58 in series)

152 Pages, 5 x 7.5

ISBN 9780228005810

June 2021

Formats: Paperback, eBook

Shush. I’m reading Eleanore Schönmaier’s poetry and I don’t want to be disturbed. Neither do I wish to disturb the poet as she works to portray the grief of a family.

Schönmaier’s husband’s sister has died and, much as we do physically and psychically when we are grieving, the poems tiptoe around familiar places trying to make sense of how everything has been altered by this death.

Early in the book, there are the setting – Crete – and the main characters – a couple – to introduce. The couple travels to the island because of mortal illness. There are a few classical references: pomegranates, which nod to the Persephone myth in ‘Slowly’; and the dying one being escorted home to Crete by her brother in ‘Ferry’, making that last voyage to the Underworld.

The sister’s name is Anthie, Greek for flower, and flowers have a part in the rituals surrounding her death. In ‘Bed’ Schonmaier’s husband is seen to pick a red flower. The same flower is later found, dying, tossed in a bed of still living white roses.

In the next poem ‘Shoulders’ the poet shifts to images in black and white as the mourners gather. Then in ‘Tasting the Fallen Sky’ we join the family on the ninth day of mourning. “Sun on the ropes / and on the wood of // the boat, and the sky / reflected in my glass // of water as if / it was a petal floating // from a blue / flower and what // is the taste of / blue?” Such a gentle voice.

And wistful. ‘Vision’ in its entirety. “You enter / her camera longing / for her selfies / and all you find / are her / visions of / you.”

Later, sitting outside in ‘Full Moon’, a leaf falls, they look at a picture of the sister, and the poem concludes with “tonight / she’s adrift in our sky.”

In ‘Compose’ the poet and her musician husband are on the beach trying to work. But they are thinking of the recently buried one. “Not decompose, / compose.” the husband says to another musician on the phone, a musical miscommunication. Contrasted with the next lines, a description found on a whiskey bottle’s cardboard cylinder. “Touch of honey / and hints of fresh // sea air.” Death. Not death.

Fruit and flowers appear in ‘Garden.’ Apricots and blossoms on the bushes outside the house where Anthie is, in a coma. “And for the first / time I really see / the design of my dress: // the passion fruit flower / from your / garden.” The flower on the dress is black.

“Her forehead’ contains the touching description of the last days, hours, minutes; and the shock when what was a person becomes a body. The poem’s language is calm and logical up to that point. Then it breaks.

The sheet

over her face.

Her mother

strokes her

body, body,

body. Her unbelievable.

Her unbelievably.

Her unbelievably beautiful

face in

the frame

the candle

the

Reminds of Jean Valentine.

I pause here to mention that not all the poems in the book are about Anthie and her family. It is as though, from time to time, the poet dances away from the life and death that is central to the book, taking side trips into her past, or describing what people do when they are not attending a deathbed. But the poems that resonated with me were the Anthie ones. Here’s another one, ‘Anthie in Flight’ in full.

While you stand

on the upper

balcony, a red

petal flies

by at eye

level.

Optimistically, the poet tosses lemon seeds into the garden in hope of future trees. But everything reminds her of what has just happened. In ‘Turquoise’ a shirt the colour of water is ironed. Then, even though the iron is off, “the steam // puffs on like an / exhalation until / suddenly it stops.”

There is a dream or vision in ‘Island’, in which they row with blistered hands through bad weather to the island where the sister has gone before them. “She waves.”

There’s a joyful description of reclaiming health after a long illness in ‘Inner.’

She finds the opening

in the fence and enters the songs

of skylarks and among

the blossoms of the

hawthorn bushes are six wild

white horses.

And another description, this one of love, in ‘Multitude.’ “they cycle down the hill at top speed holding / hands even around the most precarious corners.” Nice.

A return to sorrow (has it ever ceased?) in ‘Outside the Lamplight Circle.’ The couple walk, are distracted by talk of music, their awe of the natural world; back home, she sees “the pallor of / your grieving.”

‘Chocolatier’ is a charming poem. “In the Trojan Horse / bookstore and café / we read Cicero // who reminds us / old age will be the / best time of // life.” The chocolate the poet selects is – what else? “labelled old books: / based on the scent // of the university / library in Bologna.” And the flavour? “hazelnut, / salt, tobacco, and myrrh.” Ah, yes, myrrh, with ‘its bitter perfume’ as one line of the Christmas carol goes.

The book ends with the quite lovely poem ‘Anthie’s House.’ The last word of each line has been pushed right and irregularly spaced so, in threes, each floats freely. Like Anthie. We hope.

Louise Carson has published three collections of poetry: The Truck Driver Treated for Shock, Yarrow Press, 2024; Dog Poems, Aeolus House, 2020; and A Clearing, Signature Editions, 2015. She also writes mysteries and historical fiction. Her most recent books in those genres are The Cat Looked Back, Signature Editions, 2023; and Third Circle, land/sea press, 2022. Louise lives in the countryside near Montreal where she writes, runs and gardens