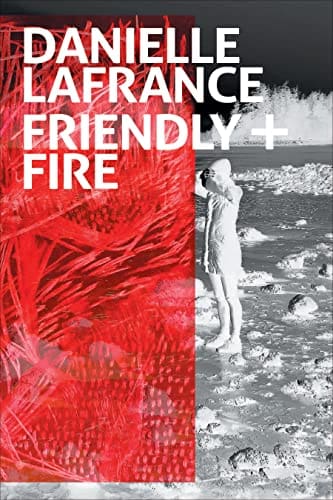

REVIEW: FRIENDLY + FIRE | BY DANIELLE LAFRANCE

Talonbooks | 2017 | 128 Page | $18.95 | Purchase online

Review by Cam Scott

—

Version 1.0.0

Friendly + Fire is a capella pornography, a multi-vocal argument concerning the collateral damages attendant upon military aggression, where the exceptional conditions definitive of combat suffuse an everyday civic. “Honey, it’s not your ginch, it’s your friends,” the opening poem taunts by way of reminder. (1)

The text commences to address itself to a lecherous, hapless, perhaps menacing ‘everyman,’ H.S, which is both a pair of initials and a male possessive pronoun, ‘his,’ stripped of it’s inner ‘I’ or subjectivity. This glyphic ambiguity betrays a parallax constitutive of the citizen, the soldier, the lover, maybe any formal identity. Endnotes to the poem ‘RIGHT-TO-MASTURBATE-AT-WORK’ remind us of the case of U.S. pilot Harry Schmidt, who laser-bombed allied Canadian troops in Afghanistan in 2002. (109) “His,” Schmidt’s, obtuse agency furnishes the poem and the book its most bathetic and recurrent signifier. The plight of this oaf is a kind of happy captivity attendant upon participation in whatever sordid endeavour comprises one’s society of a moment:

I’m a glass-half-full type of person. I’m a career military person.

I’ll stay in until they tell me to leave. I love what I do.

I never wanted to leave. (10)

Last century’s ‘Universal Soldier’ appears to be an outmoded polemical figure, for culpability extends beyond any reasons one could furnish such a (decidedly less than universal) figure. Gesturing toward an insurrectionary theorization of the social as a space of ‘total war,’ LaFrance conceives each subject as already-conscripted. Daily interpellation is not a draft one can dodge:

talk to me like lovers do then [****] me

as if someone were to persist in calling me

Male or Female even though my name is

as if someone were to persist in calling me

Mother Fucker even though my name is

as if someone were to persist in calling me

Modified Record Fire Range even though … (26)

There is a tension throughout the text between a timely adaptation of Situationist collage techniques and LangPo-descended parataxis, and the possible uses of each for ideology critique. A proliferation of impossible-seeming questions, rhetorical and non-, gesture toward the conditions subtending the text: “Why is fish farming so successful? What’s the controversy behind salt? … Why have the many problems that create friendly fire existed since the beginning of time?” (66)

The poem called ‘I SPEAK AS H.S FOR THE SECOND AND FINAL TIME’ begins with the abject apologetics of state actors, in the voice of Harry Schmidt et al, and scattering into a visceral script for resistance adapted from the call and answer of a protest around the killing of Syrian poet Ibrahim Qashoush. The transcribed outcry is buoyed by the ambient refrain of an archaic name for our contemporary, dethe. This galvanizing moment moves from the corpus of a killed poet through a crowd of angry protesters, amplifying his words; from the poet-enunciator’s own throat to those it would accuse, fusing oppositional bodies en route. A malediction, adapted from Qashoush’s seditious refrain “Bashar, depart from here,” issues forth, jinx grazing a litany of imperialist foes:

Trudeau, depart from here

VPD, depart from here

RCMP, depart from here

Canadian State, depart from here

Settler, depart from here …

Harry Schmidt, depart from here (73)

In this section, naming appears crucial to mass politics. In ‘THERE IS NO POINT SEARCHING FOR NEW LANGUAGE,’ however, the terminological means of spectacle are problematized. An insidious thesaurus appears to suggest that the discrete terms of ‘language games,’ however multiple and mutually unaccountable, are themselves subject to evaluation in exchange, such that one must contend with the real subsumption of the word-as-flesh. One cannot obfuscate the stakes of this alienation. A rose by any other name would pose the question:

Army forces say “cranium” or “skull” instead of “head.” … Go out for a boozy brunch and share intimate secrets as “friends” not “colleagues.” … “I can’t be your “husband” when I’m such an “asshole.” … Can I come to the party? I’m “queer” too!” (85)

LaFrance does not aver a nominalist use-value beneath the signifier. The slippage that an arbitrary power might artistically exploit does not pertain to any obdurate being, who has not even the dignity of persecution under the guise of a category with which they might identify. The poem of critique favours syntax, not vocabulary; the sentences that mediate the increasingly homogenizing and agrammatical terms of capitalist discourse.

am I saying friendly fire is everywhere?

nay yay (101)

This yes-or-no question is a spot-check of the reader, which binary mechanism sends up the infinitely divisible stakes of the social more generally. The individual fastidiousness of ethical consumerism is another case of this, the world reduced to flattering decisions, motion to suffice for action. Then, grimly affirming all manner of auto-antagonistic media, LaFrance ends on a note of supreme pique, apropos of the foregoing indictment: “do not call me friend” (106)