Up North with Gillian Harding-Russell

Book review of In Another Air by Gillian Harding Russell

Reviewed by Louise Carson

Geography. Do we want poems of a geographical nature? Sure we do, especially in Canada, where we grapple with so much of the stuff. And I love geography. One of my fondest memories is of the whole of my Grade 4 class, under the benign dictatorship of Mrs. Rhodes, mixing salt, flour (or was it corn starch?) and water, and shaping continents on plywood. So we learned topography, slapping on extra clumps of the porridge-like mixture for the Rockies, the Andes and the Laurentian Shield, scooping out hollows for the Great Lakes, the Mediterranean. After the muck dried, we divided the continents into countries and painted each one a different colour. So, geography – what’s not to love? Maps, place names, local history, geological time, modern architecture superimposed on landscape. It’s all good. And it’s all found in Gillian Harding-Russell’s collection of poems In Another Air.

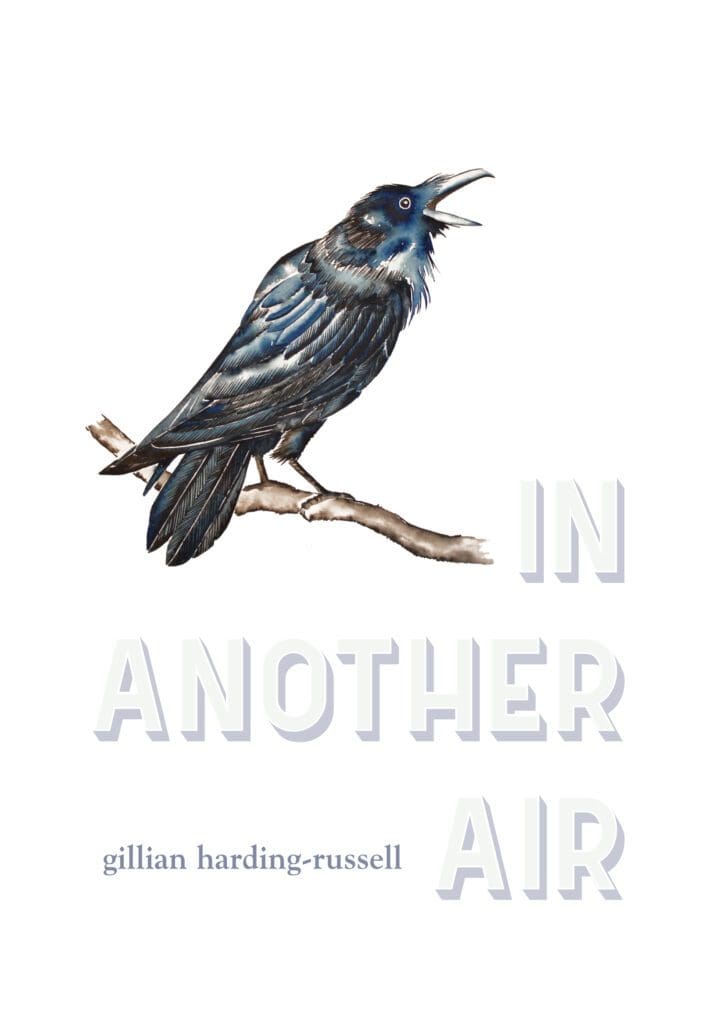

Like Canada, In Another Air is divided into many sections – six. And the image of a raven that appears on both covers, reappears at the beginning of each section. Raven: that omen of foreboding; that efficient scavenger. Four of the six sections begin with a poem about the raven and he makes his appearance in many of the other poems throughout the book. In the first poem ‘Raven in Twilight’ Harding-Russell describes the bird’s appearance and function. “Many an eyeball/pale frozen left glaring at the unspeakable/cold or the tender space of cheek above//the beard line where men are/drawn from boys has the raven/dined on,”. Brrr.

This poem begins the section entitled Proud Men Do Not Listen, the poet’s impressions of the last and ill-fated Franklin expedition. After reading these twenty or so pages of poems I thought maybe the section might have been better titled Grim, Grimmer, Grimmest. What a lesson on the suffering inflicted by geography on people unprepared for it. In ‘Returning from the dead’ we read that a frozen crewman’s body, on recovery, was intact, its eyes frozen. “A reminder/of what materials we are made, plus something else/that slips out, so elusive, when reality gets too/much for the labouring knit of cells/that must be their earthly scaffold.” Brrr again. Our body the scaffold we mount then slip from to die. Grim reality clothed in gorgeous language.

Throughout the Franklin poems, the contrast between the desperation of the explorers is juxtaposed to the calmness of the Indigenous Peoples who watch these flounderings and eventual founderings, occasionally stepping in to assist, their actions only postponing the inevitable as the explorers persist in unrealistic expectations of success. The explorers are in the wrong place, unable to adapt swiftly enough. The Indigenous Peoples are in their right place, having already figured out the necessary survival strategies.

In the section Northern and Migratory Spirits Abound, we get some delicate portraits of people and places, and a beginner’s guide to some of the spirits of the north. (Like us through her poems, Harding-Russell is a visitor to the area, not a resident.) Spirits like the one which appears in ‘Katutarjuk: ‘the odd little thing’, which manifests to the poet as sounds in the walls in the night (or is the house shifting in the cold?) and ever-rising heat in the room (or is the heat due to hot flashes?).

The poem portraits of people started to make the north come alive for me. How low the expats and temporary workers go in spirit in winter. The coming together in kindness which occurs when a Dene woman working in a restaurant takes off her coat in 30 degrees below zero to cover the elderly taxi driver who came from northern Europe long ago, who has slipped on the ice outside her restaurant. The “flesh ghost” who suddenly appears to the poet on the street on another occasion, a “Man with full red beard and trapper’s/tartan shirt”, who speaks, then, as suddenly, disappears.

And in the exquisite title poem ‘In another air (for my daughter, at Cameron Falls)’ when the poet hikes with her daughter, we get the poet’s personal feelings, knowing she must soon leave, putting two thousand miles between them, “to carve out/of this strange petrified landscape/your own life,”. Later, the mother wonders about that life “after I have gone” – but does she mean gone back to her own life or gone gone – dead? – and the last line of the poem asks “how far is that/from here?”

The animals are the original migrators. ‘Sometimes a fox’ and ‘Such angels as these’ explore their lives. But Harding-Russell chooses to conclude this section by incorporating the spirit Mahaha in ‘Inukshuk’. The inukshuk may be in the shape of a human for the purpose of turning the caribou and sending them over the nearby cliff to their deaths, much as the Mahaha may “catch//your foot, take you down/on the way/to the dangling/waterfall, tilted sky/flash of white a-roar.” Unlike the bumbling harmless Katutarjuk, the Mahaha means business.

In the lead poem ‘Raven talk’ in the next section (Mad Trapper Poems), we are given some beautiful language as the raven pulls a morsel from an animal corpse. Raven says: “‘It is my thing, my god act’: he carried it off/in his sharp suit of mirror’s black.” Similarly, in the poem which titles the fourth section ‘Dreaming on a woolly mammoth head’, we read “Your broad-boned skull…pushed low-flying clouds out of the way.”

Cartwheeling the Green-Black Spirit Air, section five, continues the poet’s descriptions and interpretations. The section title is a line from the poem ‘The wild ones’ in which the poet suggests we think of the Northern lights as an antidote to winter despair. In ‘Aerial view’ we see a polar bear with two cubs, one on her back, making her way in spring for the sea and food: “– hunger huge after the wintering in –”; and we think of the people hungry for spring, light and an end to the cold. Harding-Russell rarely writes (in this volume) a deeply personal poem. One such is ‘I can understand’ as she imagines an elderly couple inhabiting a cold cabin, needing each other for bodily warmth but, more importantly so “that they must not let the contours of despair overstep.” How to survive winter: magic, patience and companionship.

Finally, Harding-Russell turns her attention to the environment, witnessing its destruction in Littoral: Straits and Trajectories. Climate change spreads in ‘Like an albatross across the Beaufort’. The albatross, that harbinger of bad luck, is global warming, melting the north and upsetting its fragile balance. Another albatross, itself the victim, is seen decaying on the shore, its open belly full of plastic. Polar bears are hunted for trophies.

So what’s it all about, at the end? The poet advises that, if lost in all that white, one could wait for the stars: “the Milky Way/a contingent migratory/staircase to dream upon/when things went too wrong.”

As I read In another air I could see it all through her (and then my) mind’s eye. I feel I’ve made my first trip up north with Gillian Harding-Russell as my guide.

In Another Air by gillian harding-russell (Radiant Press, 2018)

Louise Carson has published nine books including mysteries, historical fiction and poetry. Her collection A Clearing was published by Signature Editions in 2015. One of her books In Which, Broken Rules Press, was shortlisted for a 2019 Quebec Writers’ Federation award. She has recently had work in Grain, Event and Queen’s Quarterly and online with Montreal Serai and carte blanche. Her next collection Dog Poems will appear in 2020 from Aeolus House. Though born in Montreal, she has lived beyond the West Island for most of her life.

gillian harding-russell is a Regina poet, editor and reviewer. She has five chapbooks and four poetry collections published, most recently In Another Air (Radiant Press, 2018), which was shortlisted for a City of Regina, Saskatchewan Book Award. In 2016, “Making sense” was chosen as best suite in ELQ/ Exile’s Gwendolyn MacEwen Chapbook Award. Poems have lately come out in The New Quarterly and Grain. Also, poems are included in the anthologies Sweet Water: Poems for the Watersheds, ed. Yvonne Blomer (Caitlin Press, 2020) and Resistance, ed Sue Goyette (University of Regina Press, forthcoming).