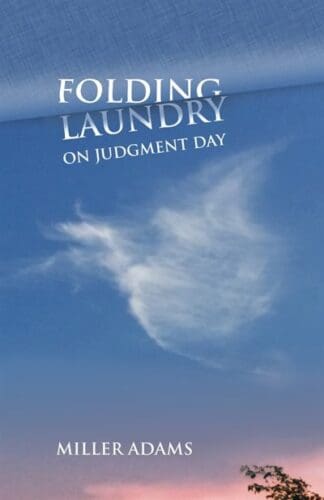

Unhappy, Women Write Poems: A review of Folding Laundry on Judgment Day by Miller Adams

Reviewed by Louise Carson

Reviewed by Louise Carson

This was a difficult book to read. Not because the poems are inaccessible, or boring, or ugly, but because they are so sad. It’s a book length elegy for a life, all lives – for life itself. It was exhausting to read. (Or did I bring exhaustion and self-recognition to the poems?) The collection might alternatively have been titled Unhappy, Women Write Poems, which could certainly describe the origin of some of my poetry.

And yet Folding Laundry on Judgment Day is filled with moments of great beauty. Of language. Of thought. Titles are, for the most part long and explicit. Section one – On the Far Edge of Memory – begins with Adams’ father and mother as small children, born at the turn of the twentieth century. A photograph of her father, aged five, is juxtaposed with one of her mother’s brother, dead at sixteen months. ‘The Child in the Trundle Bed’ portrays the terror of an imaginative child as images from fairy stories jostle in her head. “The tiger licking her face. / A princess sleeping on top of the world.”

The tiger returns in ‘The Tiger Coming Through the Window’, more frightening, keeping her awake, “wondering / whose eyes burn into her cavernous dreams, / what brushes her cheek, sighs / an insatiable hunger.” She concludes in ‘A Grace-Note for the Nursery’ that it is a mistake not to tell children about death. “Not being able to close the file, / the children risked a lifetime / of guilt and inadequacy / that, pre-dating Freud, had no deliverance.” She confirms this in ‘The Girl Who Grew Up on Faerie Tales’. “Her pets never died; they got old and went away / but never without leaving notes on her pillow; / they wrote from Faraway Lands / where they were happy but missed her.”

The stupidity of such parental cossetting made this reader’s eyes bulge. When our dog died at home one morning, I buried it then awaited my four-year-old daughter’s return from nursery school. “Where’s Honey?” she asked. “Dead,” I said. She wouldn’t or couldn’t understand until I dug up the dog and showed her its stiff cold face and she touched its fur. Adams tells us: “To this day she doesn’t know what country / she came from or how to go back or why.” Sad for her. And this displacement is evident throughout the book.

The nightmare continues in ‘A Walk in the Garden of Perpetual Rain’ where these words separately appear: shadows; chimeras; sleepless; malevolent; grave; sighs; darkened; and lines such as this: “orphaned ice-babies, crystal-swaddled, / blue-lipped slumbers, photographs of the dead.” and “a half-dug pit”; finishing with the last word – terrifying.

‘Breathing Lilacs’ is the first poem in which fear does not make an appearance, just a little tinge of melancholy for lost things – milk being delivered by horse-drawn cart; a courtship that went nowhere; the poet’s mother bringing lilacs to her own mother’s grave.

Which scene segues nicely into poems about witnessing her mother age, some of which brought tears to my eyes, and about how their relationship is fixed, unchangeable. From ‘Summer Shadows’, “Questions lost, answers safe / ground to powder by time.” Hurtful things may only be thought; her mother is too tired to hear these lines from ‘The Last Victorian’. “You made me your Victorian doll,” dressed up, hair curled, so out of time other girls laughed and this undermined the poet’s life in terms of personal appearance. The child was expected to be pretty and quiet. Witness the last two chilling lines: “Even now, I could forgive you / except for the silence.”

Before I began part two – Last Sound of Home – I took stock. So far the book contained dense poems full of backward-looking, mourning. What would part two explore?

I found poems of a person trying to self-actualize and now recounting a more recent past, that of her adult life, but still from the point of view of old age.

There are several poems about rising from bed late or staying there (because now she can), not so much fear as there was in childhood, but more regret, a feeling that her life was lacking something, that she was under-utilized. In ‘Homage to a Title Role’ the two lines “Ah yes, the homage: dear title role, mourning is so unflattering. / What would it be like if you’d been here all along?” reveal a wistful wondering.

There’s the memory of a marriage in ‘Once We Lived in a Golden Palace’ as she visits her now decrepit marital home in a dream; on waking “my eyes stay closed / search for signs of us.” And “No amount of sleeping can put it all back together.” Shades of a weird combination of Humpty Dumpty and Sleeping Beauty, or do I mean Snow White?

There’s regret for the unknowing of the one for the other in ‘A Love Poem, Perhaps’; regret for a man she knew briefly in ‘What Might Have Been a Love Poem’, in which she rationalizes “rememberings sweeter in all that unhappened.”

Adams and her mother, in ‘Driving by the Old House’ note how tidy and well-maintained the property looks. Then, “Everything’s different except the old white lilac / … / bent to the ground / with all those rustling memories.”

I must say a few words about ‘What We Remember’ which seems to be about astronaut explorers sent into space for the rest of their lives. “But nowhere – nowhere! a welcoming,” just grotesque scenes of carnage, rot, pain and death. “it all happened before our ship set down.” There were no “maps to find our way back.” “and all we can do is crumble / crackers into our soup, wait to put in at the next post / straining for signs of peace.”

I think this apocalypse is a response to how badly humans have ‘managed’ (quotes mine) Earth, how all we have left is space. And yet – the image at the end of crackers in soup is such a classic example of an old person’s humble meal, we are suddenly brought to the poet’s kitchen table where, perhaps, her soup got cold, her crackers soggy while she wrote this poem. And is the poem perhaps also a description of the absolute destruction which occurs in old age? Anyway, it’s a beauty.

And its message ties in with that of ‘Up Before Dawn, Unable to Sleep, I Read of the Proposed 100,000-Kilometre Space Elevator and Ponder the Landscape’, which is certainly the longest poem title I’ve come across, and in which I get the feeling that the poet, as she descends to her apartment’s pool, doesn’t envy those who will live in the future, possibly in space. She reflects that in the pool, at least “The water is deep and cold.” And soothing, we guess.

In section three, Afterward, Never The Same, the poems are grounded in the now, even though memory and experience are also present (as how can they not be?). And the section title appears in ‘That Window, That Rain’ where we get the beautiful line “the soft butter hum of late July”, youth, in other words, and how youth’s hopes and plans are crushed or, more usually and subtly, even when successful, modified by reality, “they’ll write on her tombstone, / afterward, never the same”. So we assume this section will deal with experience’s molding of our characters for better or worse.

In ‘Hands, A Choice’ it is the fall-out from the decision to leave a marriage (or die) that alters the poet. (By the way, this poem brought me to tears with its use of the image of passengers on an almost doomed flight clutching each other’s hands as the plane dives to illuminate our choices, and how those choices leave us loved or not.) “a whole / cargo of love stacked and steaming / and no one else to give it to.”

Folding Laundry on Judgment Day is a book by one who feels herself to be near death. The title poem of the book finds Adams cleaning and folding as she hears “Sirens Again. Time to go.” Well, it is Judgment Day. There may well be sirens. She leaves “everything” down to the last remembered kiss. “A smudged x / peels from a letter and huffs into the void.” She lets religion, history go; “memories unfold and spread, / evergreen, so many branches to sleep beneath.”

Although she spent so much of the book explaining how her upbringing made her frail, unable to bounce back from harsh reality, I think, rather it made her unbending, “raised by Edwardians raised by Victorians”, and therefore more vulnerable to breaking. (Remember the fabled oak and reed?) And there’s the pity of it. An intensely personal book.

Folding Laundry on Judgment Day by Miller Adams, Aeolus House, 2020

Louise Carson has published eleven books, two in 2020: Dog Poems, Aeolus House; and her latest mystery The Cat Possessed, Signature Editions. Her previous poetry collection A Clearing was published by Signature in 2015. Louise also writes historical fiction. One such, the novel In Which, Broken Rules Press, 2018, was shortlisted for a Quebec Writers’ Federation prize. With her daughter and pets, Louise lives in the countryside outside Montreal.