Review: Poisonous If Eaten Raw by Alyda Faber

Reviewed by John Vardon

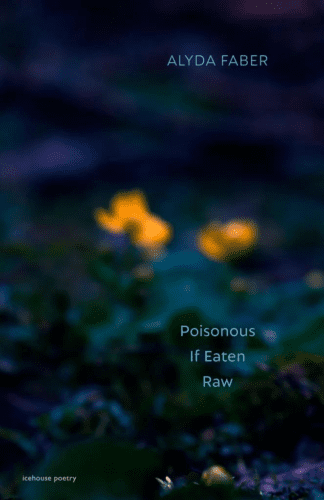

Ever since my mother died almost two years ago, memories of her surface into consciousness at all times of the day, evoked by events and objects both trivial and significant. I suspect that the same process was at work as the motivation and impetus for most of the poems in Alyda Faber’s third collection, Poisonous If Eaten Raw (Icehouse Poetry, an imprint of Goose Lane Publishing), most of which offer portraits of her mother as, on , or on a variety of objects, people, or activities, subjects as lofty as a Frank Carmichael painting or as lowly as a pair of hot-water bottles. Each of the portrait poems challenges us to find the likeness between two vastly different things, much like the analogies used in IQ testing or those at the heart of famous riddles, such as the well-known tea-party one posed by Lewis Carrroll: “Why is a raven like a writing desk?” (The fact that it wasn’t meant to have an answer never stopped readers from trying to devise one, as in “ because they both produce notes that are flat”).

But analogies have a more significant function in the way they explain the unfamiliar with reference to the familiar, what is hard to understand with what might be easier to grasp (and sometimes parent-child relationships can be very complex indeed). They initiate a learning process for those who read them and those who create them. So what we understand about the mother in these poems is integral to the poet’s understanding of a mother she may not have fully understood. To wander even more recklessly into the realm of speculation, I would say that the reason for reimagining (revisioning?) her mother in this way can be found in the book’s title, Poisonous If Eaten Raw (taken from the poem “ Marsh Marigolds”). Examining this relationship metaphorically may be less toxic psychologically than a tell-all confessional poetic memoir. So in response to the question asked in “Portrait of My Mother As Absraction”–what shape does the mother-daughter passion assume after the death of the mother?”—I would say that it takes the shape of these poems.

Biographical details about the mother (never referred to as my mother except in the titles) are not plentiful but can be gleaned as the poems proceed. Born in the province of Friesland in the Netherlands, she lived in a town with Medieval origins, married to a man (called “friend-enemy” in one poem) at the end of WWII, and immigrated to Canada, returning, it seems, only twice for visits of short-lived freedom from marital and maternal obligations. Details of family are also relatively scarce, but we can be certain that the marriage was not a pleasant one, quite the opposite in fact, as we see in “Portrait of My Mother As a Cow Being Beaten,” where the wife becomes little more than livestock, and in references to the mother in other poems as a sheep and the husband a wolf. In one of the book’s most chilling poems, “Sheep, Again-Wolf,” we find the mother recognizing that the Lord may lead his flock “to green pastures and cool waters” but also that, if you “walk up a ramp [and] turn a corner, you may find yourself on the slaughterhouse floor.”

About her other children, we also learn very little, but we do read about her eldest son in “Portrait of My Mother As Dead=Weight Lift,” the one “who claims her heart” yet, perhaps inheriting his father’s capricious temper, who once lifted her off her feet, holding her only by the head, as “his thumbs press into her cervical spine’ [and} ‘”his fingers flex the lower jawbone/ and her carotid arteries pulse against his palms,” eventually lowering her so that “the twitch of toes taps down, and then the clap of heels.” In regard to the central relationship between mother and daughter, we must largely move across the distance of metaphor, but we do get more direct references as in “Portrait of My Mother as a Black-Capped Chickadee”: “ mother daughter not enough for each other /but might have been had we looked at each other more.” The relationship, as we learn in “Rough Measure,” is “Rarely eye-to-eye, at her best, shoulder to shoulder.” We also sense an empathy if not a tenderness for her mother, who seems to have found refuge in religion and parental severity or discipline, as we see in another portrait, where her mother appeals, in both tumult and peace, to “God the host in her pyramid of prayer. In “Portrait of My Mother’s Fox Scream,” the poet explains, “Every time I hear it/every part of me stands up, wanting to answer but/ I’ve already been taught to sit still until she turns away.” Perhaps the most direct explanation of their fraught relationship comes in “Portrait: Hidden,” in which the estrangement of mother and daughter becomes clear through the different entries in childhood diary and adult journal, the former recording her mother’s activities on their visit to her homeland and the latter not acknowledging her existence at all. The two “went on like this, stiff and then stiffer/not saying much well talking so much/and staying so hidden.”

One of the most edifying aspects of these poems is that many of them are ekphrastic, offering commentary on famous paintings, photographs, and sculptures. We are once again challenged to make the connection between the artwork so deftly described and the mother so indirectly implied. One notable is “Portrait of My Mother as Pope Innocent X”—which refers to Diego Velazquez’s famous papal portrait , in which the mother, as “Her Reverence,” offers no absolution ‘for the daughter’s rages against the father.” At the end of the poem there is an even more telling allusion, this one to Francis Bacon’s famous “Screaming Popes” portrait series. In describing the mother, the poet tells us that it is “Impossible to unearth/ into paint her interred scream–Francis Bacon tried, tried over forty times.” (There is also a deliberate irony in this reference as it parallels the poet’s own efforts to “paint” the anguish of her mother.) Equally compelling is “Portrait of My Mother As Diane Arbus Photographing a Boy in Central Park.” Faber’s description of the image is exact :’ “Ventriloquist dummy face chews words/but his mechano-hands striate with rage; the toy grenade/ a lesson for the tomorrows his parents won’t see.” The parallel to the mother is not clear her but perhaps lies in the last two lines, which refer to Arbus’s bathtub suicide eleven years after this photograph was taken:“ she’ll marry her rage for ferrous water but for now/ she cradles the camera in her hands and detonates him.” One of the ekphrastic poems that deal with sculpture, “Portrait of My Mother as Boxer at Rest, figuratively compares the bronze figure to the abused mother, whose head was always the main target/in these ancient conflicts’ but who in a fight would “ never expose/her jaw like this—turning her head to the right.”

Just as many portraits in this collection are not related to works of art. Some of most memorable (and perhaps surprising) are the three devoted respectively to Alex Lifeson, Geddy Lee, and Neil Peart, the members of Canada’s legendary rock band, Rush. The list of analogous subjects is, in fact, quite diverse, animate and inanimate, ranging from architecture to zoology, but in closing I will focus on the two poems that open and close the book, both of which focus on insects: “Portrait of My Mother As a Funnel Spider’ and “Portrait of My Mother As a Moth on a Kitchen Window.” The first details the web-making and molting habits of a spider, a connection to the mother perhaps being established in the lines ‘”she bites between knuckle ridges and on the tender inner / wrist. The livid bumps linger for days.” Later we read that “A snare of filaments on the web floor/will snag the smallest spurs on insect limbs, the least iota of guilt, bad girl.” I wonder as well whether the growth transformation of the molting spider metaphorically parallels the mother’s defence strategy or perhaps the manifold ways in which her mother takes new form throughout the poems.

In the final poem, a moth clings tenaciously to the window glass during a violent storm, only to rise when it blows over:

Against the rain-dark bark

Of the maple, she’s almost spectral

As she floats up and out through holes in the net of limbs.

The words “spectral” and “limbs” are significant, suggesting an escape from the world of the flesh, a welcome ascent from earthly life.

Several poems in this collection, some of the most accomplished in fact, are not based on portraits. However, what unites them all is the poet’s meticulous attention to words.. Her language is precise and concise, both apt and original,– “admirably idiosyncratic,” to quote the book’s cover blurb—two qualities that are not easily combined. A few random examples of images that appeal to both sound and sight:”broom-swish sound of the trees,” “ bird chitter [that] snows down from iron girders,” the scissors [that] jaw across the cloth-covered kitchen table/with bullfrog croaks’” and “her [a wren’s] chiding a tumble dryer’s clatter of zippers, snaps, and huff of turning clothes.”

Not long after my mother’s memorial service, a colleague who had heard me mention her death asked, “What was she like?” The question was overwhelming given the memories and emotions it brought on. But I was also struck for the first time by the form the question took, the built-in, barely recognized simile, a question we ask about new experiences and difficult-to- describe emotions. If I had read this book at the time, I might have answered with another of Faber’s lines (one that was apparently the original title of this collection) : She was “like the rain, in all the ways that it falls.”

This review was first posted in The New Quarterly

John Vardon worked for four decades as an English instructor at Renison University College and as a tutor in the University of Waterloo’s Writing and Communication Centre. For almost as long, he has been a poetry editor for The New Quarterly literary magazine.