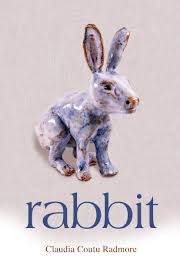

What the walrus said: a review of Claudia Coutu Radmore’s rabbit

Reviewed by Louise Carson.

While Claudia Coutu Radmore may not talk “Of shoes and ships – and sealing wax – of cabbages and kings”, she does, in rabbit, her latest collection of poetry, cover parrots, Elizabeth Bishop’s childhood, Fogo Island, Montreal history in the 1950s, anatomy, geology, folk art – I could go on but you get the idea. What I liked about this book was how most sections (there are seven) were completely different one from the other.

While Claudia Coutu Radmore may not talk “Of shoes and ships – and sealing wax – of cabbages and kings”, she does, in rabbit, her latest collection of poetry, cover parrots, Elizabeth Bishop’s childhood, Fogo Island, Montreal history in the 1950s, anatomy, geology, folk art – I could go on but you get the idea. What I liked about this book was how most sections (there are seven) were completely different one from the other.

However there are two sections which resemble each other: On Fogo; and Elizabeth Bishop House Poems; in that both take place in Atlantic Canada. Fogo is an island off Newfoundland’s northeastern shore while Bishop’s grandparents’ house is in Great Village, Nova Scotia on the north shore of the Bay of Fundy near Truro. In the Fogo poems we get a great sense of the people of the place as well as the flora and fauna. The poet was there in berry-picking time and got to do that, feeling right at home with the locals. Not so much sense of the people at Great Village. Here, the poet is more concerned with the past, with the life of a great poet, and how the happenings here in Bishop’s family circumstances may have changed her from a happy little girl to something else.

If you’ve read other reviews of mine you will know that I like geography, I like hearing of new places. I know it’s not like harvesting impressions in person, but perhaps I’ll never go to Fogo Island (though I’ve been near Great Village), in which case, the Fogo poems will make a decent substitute.

I liked hearing about the vegetation of the island, so marine, so unlike that of my reality, and I enjoyed vicariously picking berries. In ‘the man from shoal bay (that’s shawl bee, me darlin’)’ we meet one of the island’s many characters. What are we to make of Osmond, already an expert hunter and fisher, who also wants to be the best jam maker on Fogo? At the market, the other men tease him – “hey Osmond, they’re lookin at yer jam” – I suppose, for engaging in less than manly pursuits. We like Osmond and want to know about him as the poet does; her last fragment of this poem being “and there’s the wonder of it”.

‘berry grounds’ takes us through a long catalogue of plants until the poet pauses for a breath to say “tuckamore, tuckamore. / your mouth wants to play with the word in the wind.” And she finishes the poem “till the wind knocks / you back toward small ponds stocked with clouds.” Thank you for that lovely image.

The style here is unpretentious. One phrase or observation runs out of and in to the next and before you know it, you’ve been on that walk, you’ve picked those berries, you’ve met those people.

The note at the back of the book is a help in interpreting the Elizabeth Bishop House Poems. It concerns her family history, which is sad. I won’t give it away, but reading the note first is a good idea as said history then tinges the otherwise happy poems where we are inside the little girl’s head as she plays in and around her grandparents’ house. The final poem of this section ‘mudflats by the cemetery’ is a beauty. We go on this walk too as the plants make September’s “tapestries among tapestries” and “the air sizzles with bees” until we get to the mud “and the sky lies flat on the flats” and we are “seeing that glistening surface”.

A different geography, a more personal one awaits in En Famille, a section of four longer poems which explore the history of Coutu Radmore’s mixed English and French heritage through portraits of the two sides of her family, and the parts of Montreal where each lived. Coutu Radmore seems to celebrate the differences of language and religion; as a child they were unimportant to her and this lets her just report each scene and enjoy the people for what they are – relatives, who, mostly, love her. At the end of ‘ma famille française’ when a favourite aunt, Madeline, lies ill (we assume many years later), the poet states touchingly “When she was very ill, she was surprised I’d come / from Ottawa to see her, but then, I would have walked.” This walking harks back to the hours-long childhood hikes she and her sister made from one end of Montreal to the other, from English district to French, to visit family in the 1950s.

I mentioned parrots in my introductory paragraph and Coutu Radmore devotes a section to her lorikeet Desirée. In ‘wild thing desirée’ we discover complicated, unknown (to me), and unique avian anatomy, the words of which the poet uses to emphasize the difference of bird from human. But it is this form that the poet celebrates in ‘her body bending’ and ‘she walks in beauty’, the latter which contains the lines “her tail a pointed brush // brimful with words that only birds / can see, ever traces as she walks / a birdly-eloquent poem”. The final poem in this section, ‘sacrament’, is my favourite. The poet meditates on dying in her chair with only her “small parrot” to “perform the rite / in silent vigil” which others might crave from a priest or other human. For Coutu Radmore, the beloved Desirée would be good as or better.

Ghost Apples, as a section, proved interesting. Here were the “cabbages and kings” I alluded to earlier, as the poems mostly attacked the problem of reality versus unreality in various guises. In the section’s title poem, we have the problem of ghost apples, frozen in autumn, but still preserving their external appearance. However, if we were to touch them, they would collapse into mush.

In ‘of never writing home’ the poet explores the ease with which we can now source information, the vastness of same, and the impossibility of fathoming even a tiny percentage of the facts out there, coupled with the strangeness of a fast-changing planet. These two have driven the poet to hide in a closet where she awaits communication by a note slipped under the door. So at the end of the poem we feel we are at the beginning of something and it ain’t good.

A similar ominous feel comes in ‘the letter’ possibly addressed to a child. It is full of dread which the poet is yet drawn too and which leads to a suicide. Quite creepy.

In ‘jewels’ the poet is just going along enjoying the day when wham! She’s reminded she’s on a planet full of false advertising, greed. The consolation turns out to be her backdrop of dear ones. “jewels in a crown, like those close to me / filled with light”. Likewise, as in ‘a house for Z’ the

poet tries to define or confine tenderness which “burns myrrh” that bitter perfume of mourning, evocative of the tomb in Christian stories of the nativity, so tenderness becomes half sadness, half joy.

There are two very short sections in rabbit and one is ‘a bowl of light’. The language is oblique and layered, about memory. A whole life I thought as I read it. A life symbolized by a bowl, hand-made and what more is a life, anyway, than a container for thought, emotion. The poem ends “it can undo you / this bowl of light”.

We come now to the title section Rabbit, the actual poem of which is entitled ‘our very own leporid’. It’s the touching story of a backyard rabbit, fed for seasons, then sheltered in the house as she died. In it, the poet hopefully offers the idea of a future soul existence of playful fun for bunny and human, but towards the end of the poem the grimness of death creeps in. “how bereavement mounds / like heaps of dying bees / and mountains of bison bones / how to learn to live with all these walls / these mounting griefs” and we are reminded that all deaths are one death really and that our own, and that there is no party in the afterlife. “she was already … in the earth” but we can imagine one if it comforts us. We can imagine one.

rabbit by Claudia Coutu Radmore, Aeolus House, 2020.

Louise Carson has published nine books including mysteries, historical fiction and poetry. Her collection A Clearing was published by Signature Editions in 2015. One of her books In Which, Broken Rules Press, was shortlisted for a 2019 Quebec Writers’ Federation award. She has recently had work in Grain, Event and Queen’s Quarterly and online with Montreal Serai and carte blanche. Her next collection Dog Poems will appear in 2020 from Aeolus House. Though born in Montreal, she has lived beyond the West Island for most of her life.

Including three years training teachers in Vanuatu as a CUSO cooperant, Montreal-born writer Claudia Coutu Radmore has lived, taught and created art in Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba, and China. She is the President of Haiku Canada. Claudia started catkin press in 2012, and along with several full collections, Accidentals (Apt. 9 Press, Ottawa) won the 2011 bpNichol Chapbook Award. On Fogo, poems short-listed for the 2017 Malahat Long Poem Contest, was published by The Alfred Gustav Press (Vancouver) in 2018. A poem from the camera obscura (2019, above/ground, Ottawa ) is included in The Best Canadian Poetry of 2019. A new collection rabbit (2020) is out with Aeolus Press.