Review: Rags of Night in Our Mouths by Margo Wheaton

Reviewed by Michael Edwards

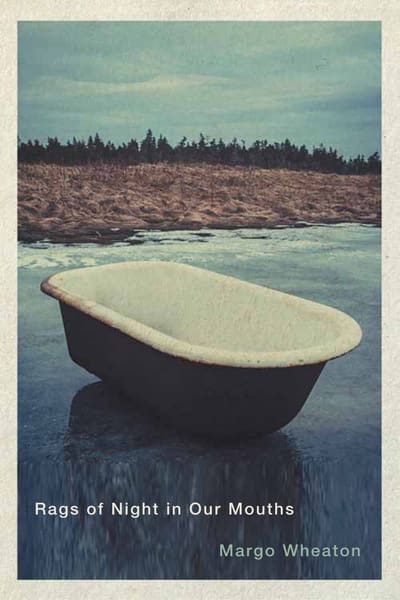

Rags of Night in Our Mouths by Margo Wheaton (MQUP, 2022)

I.

Margo Wheaton’s second poetry collection, Rags of Night in Our Mouths, takes the form of a place-based memoir, presented in three ghazal sequences.

In what the book’s jacket describes as a “Maritime gothic,” the work is set in areas around New Brunswick’s “Tintamarre” Marsh, often within the speaker’s childhood family home.

Around place and memory Wheaton generates an energy, a tone which pulses through the work.

The speaker’s voice drifts about the place, a witness to the life of a family haunted by the un-deadness of shame, trauma and grief—the memory and presence of “generations of black moods fill the kitchen.”

The reader experiences a ghostly sense of the “liquid oblivion” of familial alcohol misuse and addiction and an atmosphere of lingering “heartbreak,” which they liken to a “slow burning building.”

II.

The poet wrestles with the problem, through language, of representing the complexities of the emotional enmeshment of memory. Metaphorically, the speaker chokes on the “rags of night.”

Poetry then becomes a way to sing “the unsaid, one / resounding word.” And what matters? “Only the rhythms / the songs.”

III.

Poems, often cascading through lateral associations, are supported by the strong work of simile. Sparse and fragmentary scenes find richness in the use of figurative language, the speaker and family members, “regarding” each other “like neighbouring towns.”

Often the power of memory is found in image. It is interesting to pay attention to moments of colour washing over the bleakness of grief.

“Cover your eyes with thought” and a palette emerges—the descriptive “hue of rotting peaches, “the sublime “rose-gold light” and “sheer lime-gold.”

IV.

At points, there is a sense, as a reader, of feeling unanchored, adrift in a non-contextual and abstract space. Pronouns can also sometimes be hard to pin down. But recalling what the speaker instructs, that “the rhythms / the songs” are the important things, on further close reading, the logic of the work clicks. The poems need to be fragmentary, kaleidoscopic for the way a mind, passing through memory—always in media res—blurs the details like notes across a sheet of music.

Readers may be taken by the impulse to find a narrative thread through the book. This inclination is something the ghazal form mediates very well as it mimics, with authenticity, the fractal reconstruction of memory. What emerges is a powerful kind of family anti-narrative.

V.

Thinking about the oblique quality of memory—singing as a way to keep trying, singing as a response to an unbearable strangeness. Coping with discomfort has a music of its own. The “marrow echoes of generations / falling”—falling into the surreality and dissociative effect of the lyric.

VI.

A reader attuned to the literary geography of the work will find, in the final piece of the second sequence, a paratactic moment, “water, blood, skin,” a nod to John Thompson’s work in Stilt Jack.

This is a good reminder that there is something enduring about the physical and metaphysical qualities of the Tantramar marsh. The landscape as a place deeply imprinted into the collective consciousness of Canadian literature.

VII.

In the book’s final section, Ravaged, poems are composed in single lines, standing spare against the white space of the page, formally stripped away, in connection with content.

“Lost in a season of understanding,” the poet contrasts the violence of development with the delicateness of the life cycle of an insect, the sedge, pointing again to the entanglement of form, the ghazal and its ability to hold this all-at-once-ness.

The poet writes, “greed has stripped us, rendered us bare,” making a move into ecocriticism. The work thinks about erasure by development, loss of landscape as loss of memory.

There seems to be a certain type of poetic charge or movement in the liminality of the marsh—playing against notions of time and space as stable, the dynamics of pain and beauty in a landscape.

Wheaton leaves the reader with an intertidal sense of memory, a phantom perception, an interruption flooding across the present moment—“the ageless pounding of water” and “the rhythm of its burgeoning speech.”

Rags of Night in Our Mouths by Margo Wheaton (MQUP, 2022)

Margo Wheaton is the author of The Unlit Path Behind the House, which won the Fred Kerner Book Award from the Canadian Authors Association. She was born in New Brunswick and lives in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Michael Edwards lives and writes on the traditional and unceded lands of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam) people (Vancouver, BC). He is a graduate of The Writer’s Studio at Simon Fraser University and editor of Red Alder Review.