Review: The Griffin Poetry Prize Anthology 2021

Reviewed by Josie Di Sciascio-Andrews

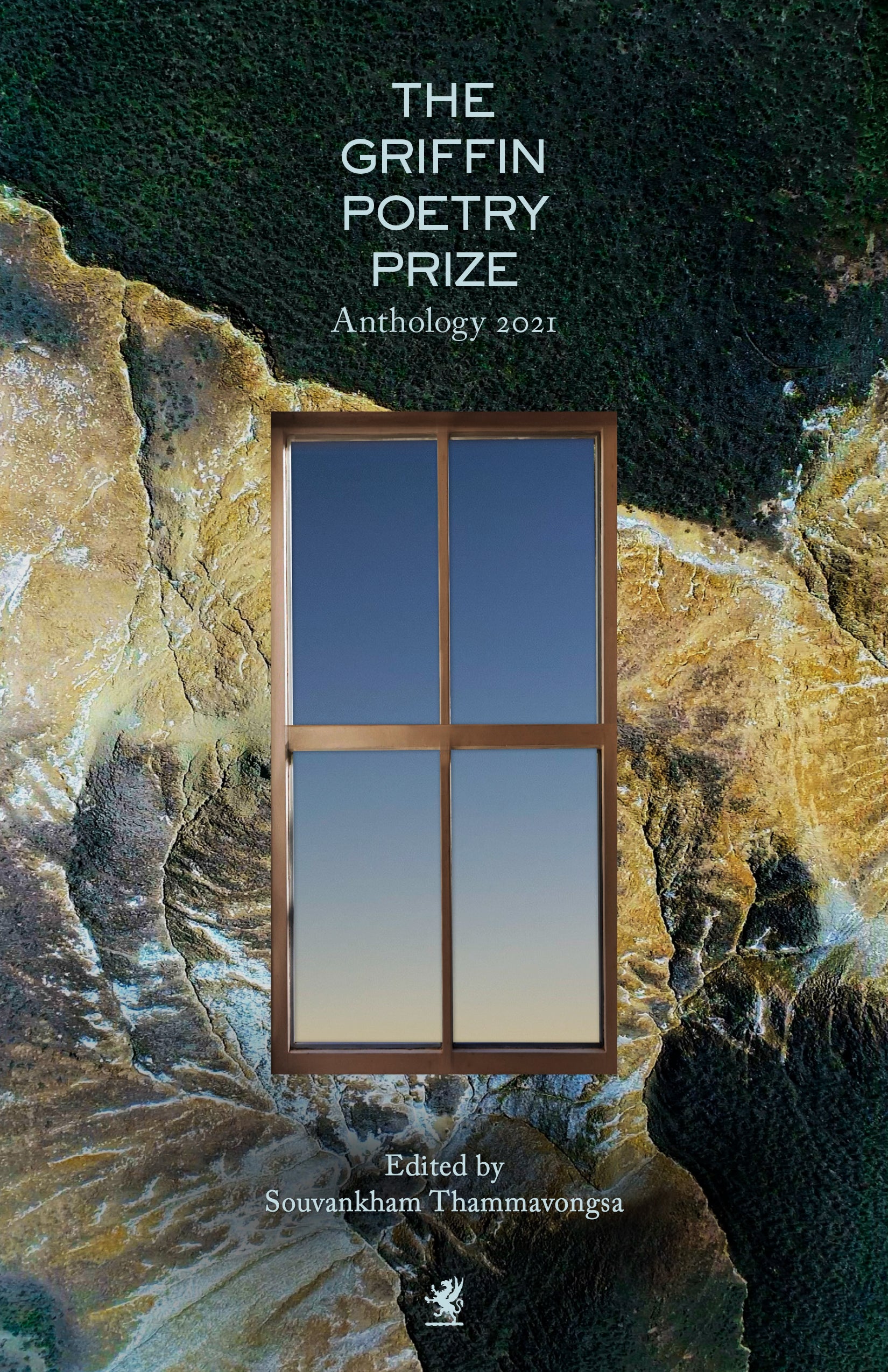

Poetry, azure coloured glass of a sunlit window, encases celestine light on the glossy cover of this book, softening the view of reality’s stark terrain. An aperture over a land mass in the middle of the deepest, dark ocean, soon shattered in the inset cover image, by the blow of a sledgehammer or a bullet breaking through the barrier to reveal a sequence of sublime poetic voices. On the back inset cover glows a golden blue horizon, unimpeded by frame or glass: reality reintegrated by the synthesizing power of words.

Prize-winning poet Souvankham Thammavongsa, editor of this anthology, eloquently prefaces each selection. One cannot help, but notice a recurring theme of death throughout both the international and Canadian shortlist. From Victoria Chang’s Obit, to Valzyna Mort’s Music for the Dead and the Resurrected, to Srikanth Reddy’s Underworld Lit, Tracy Smith’s & Changtai Bi’s translations of Yi Lei’s book My Name Will Grow Wide Like a Tree, Joseph Dandurand’s The East Side of It All, Canisia Lubrin’s The Dyzgraph*ist, and Yusuf Saadi’s Pluviophile. Gleaned from a time in the throes of a global pandemic, these poems seem to be serendipitously threaded with the theme of death in all its permutations, as if all these voices were drawing from one, same, global poetic vein.

My father’s frontal lobe died unpeacefully of a stroke, writes Victoria Chang, as she pronounces her own death on the same date as her father’s. She metaphorically dies when her father and his language die. Now his words are blind. Are pleated. Grief takes root and lasts forever spreading to all aspects of a person’s life. Finality sets in and the obituary is the moment when someone becomes history/ when we die we are represented by representations of representations/ often in different forms/ I go through corridors looking for the original/ but I can’t find her.

In Music for the Dead and the Resurrected, Belarusian poet Valzhyna Mort tells us that here history comes to an end/ like a movie/ with rolling credits headstones. These poems are disturbing in their surreal images. An air raid rings like a telephone from the future/ her heart an octopus/ New Year in Vishnyowka/ snow glints and softens a pig’s slaughter. These are powerful, concise images reminiscent of Sylvia Plath’s poetry. On the wall/ a carpet with peonies/ their purple mouths/ suck me into sleep/ and a cat licks its gray paw as if sharpening a knife. In these poems the object becomes the subject, alive with thought, movement and voice. Having climbed into my lap/ the accordion composes its heavy breathing. In Nocturne for a Night Train, we read the trees I’ve glimpsed from the window of a night train were the saddest trees/ they seemed about to speak/ then vanished like soldiers. So too in a tall glass/ a spoon mixed sugar into coffee/ banging its silver face against the facets. In this inverted phantasmagoria of consciousness reversal, anything can happen. In lit up windows/ people seemed to move/ as if performing surgery on tables. There is something eerie that fills us with dread in these metaphors, as if we are inadvertently witnessing a murder. Our own? Why does unfolding this starched bedding/ feel like skinning someone invisible? / why can’t the spoons/ head down in the glass/ stop screaming? Is it too late in our technological era to save our souls? This poet seems to think so: I was extracted, she writes, my face turns into a document.

Continuing on the same thematic thread of surreality and death, American poet Srikanth Reddy’s Underworld Lit guides us like Dante on a tour through the underworld. These are dreamy, surreal poems grounded in everyday reality, then digressing and blooming into myriad sub-worlds of the imagination. I lifted the receiver/ the sound it emitted seemed otherworldly/ like somebody’s finger playing on the wet rim of a crystal bowl/ in a derelict theater before the wars/ the rings of Saturn kept turning in their groove/ I dialed 1-800 Inferno/ and before the first ring/ a woman’s voice answered/ is it you? In poem VIII a magistrate assistant was taking a nap in his cabinet of pain/ when a motorized airport staircase/ appeared taking him down a path hidden by rustling thickets of bamboo/ to a clearing/ where an enormous mirror waited in the moonlight. Haunting past lives flash before him from the mirror: the face of a donkey, a girl wringing blood from a cloth and a high official in an old Ming costume. As the magistrate is enthralled by these visions, a servant arrives to let him know that his life was just a draft, not to be circulated. In poem IX Reddy describes the ethereality of communication. What we say, its relevance emerges and disappears in waves of importance and banality, the remains of a ziggurat, which may be the original site of the tower of Babel, symbol of human miscomprehension. In poem XIV we encounter a fill in the blank test asking specific questions about thanatopography, the drawing of the map of death, its symptoms and the changes it brings. This is poetry of the dying, indeed. Dante features again in Reddy’s last poem in the anthology: he went all the way through the underworld and saw the stars again, says a metaphorical, rural, remedial poetry student of professor Reddy. He tells her it would be impossible for Dante to crawl through the center of the Earth because, as everybody knows,the planet’s core is very hot. There are no definite answers in life nor in poetry. Yet, the open ended nature of reality and human thought are wittily demonstrated through humor, dialogue and the surreal.

Tracy K. Smith’s and Changtai Bi’s translation of Yi Lei’s Chinese poetry seems to break away from death to hope, but we soon find ourselves in the same grooves of mortality as the previous poems. When life ends/ memory endures/ what persists attests to the spirit. A furtive joy is gained by stealing a cutting of a plant from someone else’s garden. Is meeting out of habit any worse than coming clean? / such secrecy unravels me/ my name for you creeps off like a plant that has outgrown its pot. The beauty of these poems culminates in lines that encompass the totality of life, lines such as out past the horizon and delimited by an unsentimental fog/ past the farthest deep grasses/ the flowers fading and blossoming/ falls the torrent/ the monsoon/ in which a woman exalts day and night/ her face danced upon by rainwater/ I out past a distant heaven/ and remotest earth/ and the outer banks of the heart. This is descriptive writing that seems to encompass everything. It is poetry at its best.

From the Canadian shortlist, Joseph Dandurand has remained etched in my heart at first reading. As Souvankham Thammavongsa writes, his poems are deeply spiritual invocations extricated from poisoned air by a fallen angel. In The Shame of Man the poet bears the shame of not having been able to save his sister nor all the other women murdered on a pig farm. It was always death/ as the new day began/ the pigs of the world would feast. There is regret and helplessness. All I can do is stare at my hands as they strangle an imaginary evil. In Street Healer, the poet transforms into a sasquatch. He heals people with his words. He tells them it will be alright/ as they carry on with their misery. In I Don’t Know When I’m Going, a man is shooting drugs. I put a stake into my arm/ to become Christ on the Cross/ as I sit in my squalor/ I remember being a small child on an island upriver/ I remember the salty smoked taste/ as my mouthful of new teeth chewed and chewed/ but now I do not have any teeth/ and now I inject my liquid dinner into an old arm/ the sky blackens again as I sit here and chew away what is left of me. In Songs of the Mountains and Sturgeon’s Lover, legends and myths surface, while in Days into Days, the poet paints reality and time altered by depression. They say that God is there/ but we have never seen him/ and his son sits on a wall in our old church/ where we will never kneel.

Canisia Lubrin’s poetry, winner of the Griffin Prize, gives us a lot to ponder right from the title.

The Dyzgraph*st, with an asterisk instead of the vowel “i”, reads a bit like a cryptic internet password, all the while alluding to someone with dysgraphia, a condition of impaired letter writing, as in dyslexia, a juxtaposition of syntax. Words are arranged just so in these poems in order to form the shape of the shape of a thing that light curves over time/ length to width/ to depth/ and all of us its information. Beautiful lines push the boundaries of language and captate the zeitgeist of a poet’s raison d’etre. Here beginning the unbeginning/ owning nothing but that wounding sense of waking to speak as I would after the floods/ the moon/ a moonlit knife. The importance of the pronoun “I” is pivotal and perhaps the asterisk hiding it in the title highlights its importance. I was that speck in the multiplier of myself/ deja vu, an early stage/ what I have learned/ new language held in the nowhere of my blood/ up against the page.

Pluviophile by Canadian poet Yusuf Saadi ends this collection with poems that search everywhere for mystery, for magic, for beauty. This poet hears whispers in the letters and in his poems everything becomes relevant. Everything is alive and nothing is to be taken for granted, as in the elencation of things that affect our days moment by moment. Imagination gives life to a forgotten Twix wrapper. Now we soliloquize/ though prey to seagulls’ beaks/ and sunbathe on the asphalt when the maelstroms grant us mercy. Almost synchronistically, these poems tie the theme of death back to the loop of this poetry collection. The poem Is The Afterlife Lonely Too asks questions about life and when that fails, about death and the afterlife. Do the dead hide inside poems?/ in the corridors between stanzas?/ and failing the soul search that follows, from which you promise yourself to be reborn?