Review: Thimbles by Vanessa Shields

Reviewed by Josie Di Sciascio-Andrews

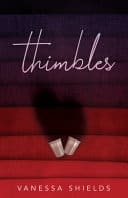

Thimbles by Vanessa Shields (Palimpsest Press, 2021)

In poetry, everything has a deeper meaning. A thimble as a mythopoetic symbol evokes a sense of immunity and self-protection against the pain and bloodletting of life’s allegorical needles. It is a shield against pain. Interestingly, the poet’s last name is Shields, giving the title a more layered sense, whether intentionally or synchronistically. Thimbles are also evocative of fairy tales. At the beginning of Snow White, a queen sits at an open window during a winter snowfall, when she pricks her finger with her needle, causing three drops of red blood to drip onto the freshly fallen white snow on the black windowsill. * Then the queen makes a wish to have a daughter with skin as white as snow, lips as red as blood and hair as black as ebony.* The fairest one of all, a wish that came true when she gave birth to Snow White, the girl who engendered envy and vindication by a competitive step-mother queen. The story is a quintessential archetype of the danger of not wearing a thimble, of the danger of goodness and beauty at the mercy of narcissism. Even upon the death of the queen mother, a daughter carries the gift of beauty and goodness forth into the future. Love is a transformative power across the generations, across continents and time. In her new collection of poems, Vanessa Shields spills thimbles of memories of her beloved grandmother: images and words that stitch back the fabric of the soul of a woman’s life, a love story, a tale of endurance and resilience. Poet Vanessa Shields wonders what she can keep of her grandmother’s, to make sure she is remembered.

In poetry, everything has a deeper meaning. A thimble as a mythopoetic symbol evokes a sense of immunity and self-protection against the pain and bloodletting of life’s allegorical needles. It is a shield against pain. Interestingly, the poet’s last name is Shields, giving the title a more layered sense, whether intentionally or synchronistically. Thimbles are also evocative of fairy tales. At the beginning of Snow White, a queen sits at an open window during a winter snowfall, when she pricks her finger with her needle, causing three drops of red blood to drip onto the freshly fallen white snow on the black windowsill. * Then the queen makes a wish to have a daughter with skin as white as snow, lips as red as blood and hair as black as ebony.* The fairest one of all, a wish that came true when she gave birth to Snow White, the girl who engendered envy and vindication by a competitive step-mother queen. The story is a quintessential archetype of the danger of not wearing a thimble, of the danger of goodness and beauty at the mercy of narcissism. Even upon the death of the queen mother, a daughter carries the gift of beauty and goodness forth into the future. Love is a transformative power across the generations, across continents and time. In her new collection of poems, Vanessa Shields spills thimbles of memories of her beloved grandmother: images and words that stitch back the fabric of the soul of a woman’s life, a love story, a tale of endurance and resilience. Poet Vanessa Shields wonders what she can keep of her grandmother’s, to make sure she is remembered.

On the cover of the book, pleats of incrementally darkening hues of red fabric, upon which shine two silver thimbles, spread across the spine to the back cover, where scissors, a spool of thread, a needle and measuring tape are laid ready for new creations. As we turn the cover, a blood-red page welcomes us into the collection followed by white pages with the title, the name of the poet in lower case cursive and an eclectic couture of poems. Thimbles is dedicated to the poet’s grandmother, Giuditta Merlo Bison and it is divided into three sections: un bacin d’amor, only the good lasts, domani è un altro giorno.

In un bacin d’amor, the poems give us sketches of nonna as a young woman. Here we get a description of who she was as a person before she moved to Canada, married and had children. This first section begins with a quote in Italian, written on a bridge in Italy. On the bridge of Bassano we will hold hands and we’ll share a kiss of love. Then the images of memories turn to sound and nonna’s inner child emerges lost in need of a mother turned to dust. Her pain is an ohh drawn out like a line with no ending thickening in the sunrise, as she points back in time to fingers unbent, shining tips thimbled, sewing sewing sewing. The poet likens her grandmother to Ponte Vecchio Palladio’’s architectural gem, blown up and rebuilt again and again. Like pieces of a puzzle soon to reveal the portrait of the poet’s beloved nonna, each poem in the first part of the collection metaphorically stitches together a tapestry of a life: from childhood to old age, of a woman whose life spans from the mountains of Veneto to the shores of Windsor Ontario. She is a woman who sews through a world war, thinks less of the bombs than the bobbins and basting. Thinks about her heart reaching out for nonno. Handsome. Religious. Soon they will spend time alone in the mountains. We see a young nonna whose smile is bigger than the valley and has mischief in her eyes, with shoulders squared to the horizon, courageous and ready. A young woman who willingly emigrated to Canada to follow the man she loved because that’s what life was for, to be married, to make a family.

The second section of Thimbles is entitled Only the good lasts. In its pages we see a deepening summation of Vanessa Shield’s beloved grandmother. The poem Nonna Never Complained, is pivotal to the cover image of the book. We read: I wept in the woven fabric of her. In the middle section of poems there is an intensifying of the weaving of threads that reconstitute nonna’s image, then a sporadic unravelling which alerts us to the slow, but steady decoherence of her mind afflicted by dementia. In I Call Them Episodes, nonna freezes mid-step or sentence, the disease a seam ripper, her eyes vacant with loss of patterns, entranced in an unanticipated loss of self. The poet’s grief in knowing she is losing her precious nonna seeps through: you were our thimble. The metal casing holding us together, grief holding me like blood holds memories and pain and colours. The grand-daughter understands her grandmother’s life more clearly now that she’s about to lose her. Maybe she wanted to make all the decisions, but it was too hard a fight and so she made the best decisions of all, turn dignity into a pattern, stitch the needs into a shirt sleeve, sew, cook, clean, iron, drink and love.

As nonna approaches death in the ghost silence of the hospital room, the poet and her grandmother wait for the end, alone in the healing purgatory of time. As nonna is about to leave the earthly plane, the poet sees nonna’s spirit in the hue of red in her cheek skin. We read you are an extension of me and a synopsis of nonna’s life: out of all of it, only the good is what lasts. Soon grandmother will die and her grand-daughter will take over as lead seamstress. She will follow in nonna’s footsteps, be her mouth, her voice, tell her stories. She will use the same threads, the same thimbles. As nonna’s dying body becomes a realm slowly separating from the motherland, her body an ocean liner death at the helm. The poet knows nonna is very close to death by her mouth always open now, an inviting entrance for the IT that wants to take her.

The third and last part of the collection is domani é un altro giorno (tomorrow is another day). You can tell these are words nonna used to say, words she would probably use in a situation like this. Words of wisdom, to make existence bearable when it becomes too painful to go on. This last portion is briefer than the other two sections. There are no words to describe the ultimate loss of someone we love at death. The poet writes: The language of loss is wordless. Nonna’s stillness is impossible, she is just a body now. In the poem Black Body Bag On a Stretcher, we hear the zipper, its chain of teeth, its closing mouth a final hymn. At the funeral home people drone in like vibrating memories, but the poet knows nonna’s spirit is not there in the casket. She stands courageous on her favourite mountain in Italy, our mourning a songbird’s trill caressing her earlobe.

We feel the poet’s grief intensely in the last few poems as the realization of the finality and irrevocability of death becomes her reality. I want you back in the kitchen and where are you nonna? As a living legacy to her grandmother’s life, the poet writes that it is her responsibility to extend the story of her life where the language of her essence moves like blood. The last poem in the book is written in the style of a responsorial psalm. It is a prayer from a granddaughter to the nonna she loved so much and who loved her unconditionally. The choral response is when I die I want your thimble on my finger, a thimble of talent, of craft, of selfless dedication and sacrifice, of love. A thimble pushed on so tight it can match the memory of nonna’s heartbeat; a song of memories stitched into the poet’s soul. Storms rush out of me sometimes as I gather tears in my thimble, she writes, and as we turn the page, we see a photo of the poet with her beloved nonna Giuditta. Above the photo and below is a definition of the word closure, or chiusura in Italian: the area of a garment that opens and closes for dressing. And as we zip up the book and Vanessa Shield’s nonna’s life, we are glad to have been introduced , not only to the story of one amazing woman, but to the eternal legacy of love and relationship she wove with her grand-daughter, who with her writing re-stitches and re-embodies her memory through space and time.

*Excerpt of the tale of Snow White from Wikipedia.

Thimbles by Vanessa Shields (Palimpsest Press, 2021)

Josie Di Sciascio-Andrews is a poet, author, teacher and the host & coordinator of the Oakville Literary Cafe Series. Her latest book of poems Sunrise Over Lake Ontario, was launched in 2019. Her previous poetry publications include: Sea Glass, The Whispers of Stones, The Red Accordion, Letters from the Singularity and A Jar of Fireflies. Josie’s poetry has been shortlisted for the Malahat Review’s Open Season Award, Descant’s Winston Collins Prize, The Canada Literary Review, The Eden Mills Literary Contest and The Henry Drummond Poetry Prize. Her poetry has won first place in Arborealis Anthology Contest of The Ontario Poetry Society and in Big Pond Rumours Literary E-Zine. Some of her poems feature on The Niagara Falls Poetry website. One of her pieces was included by Priscila Uppal in Another Dysfunctional Cancer Poem Anthology, Mansfield Press, in 2018, rated by Chatelaine Magazine as one of the best Canadian poetry books of 2018. Josie is the author of two non-fiction books: How the Italians Created Canada (the contribution of Italians to the Canadian socio-historical landscape) and In the Name of Hockey ( a closer look at emotional abuse in boys’ sports.) Josie teaches workshops for Poetry in Voice and for Oakville Galleries. She writes and lives in Oakville, Ontario.

Vanessa Shields is the owner of Gertrude’s Writing Room—A Gathering Place for Writers. She is the author of Laughing Through A Second Pregnancy (2011), I Am That Woman (2013), and Look at Her (2016). You can find her mentoring, editing, teaching, and writing at Gertrude’s or having a dance party in her kitchen with her handsome husband, two amazing kids, and two golden retrievers. Visit her website: www.vanessashields.com. She resides in Windsor, Ontario.