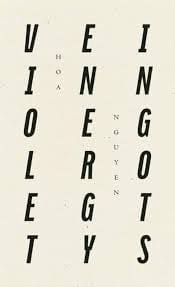

REVIEW: VIOLET ENERGY INGOTS | BY HOA NGUYEN

Wave Books | September 2016 | $18.00 | Purchase online

Review by Cam Scott

—

Opaquely personal, spare but social, Hoa Nguyen’s writing more than most fulfills Louis Zukofsky’s mandate of a poetry arranging “minor units of sincerity” into shaped apprehension. Nguyen’s verse flits and fidgets by the phrase, conveying something of the poem’s occasion to the reader but in passing; which is not to say that these poems are imprecise. Rather, each is of a moment, and Nguyen repudiates the pictorial urge of the collector for tracings of a dailiness insusceptible to capture in itself:

What are these metallic squiggles

and yellow that giant urge

to hover The place of death

and lentil-burger dinner (10)

Anti-abject, antsy-urgent, these poems rely upon the well-observed phenomenon that vocabulary is itself ticklish, inter-associative and never really all that vague. Nguyen’s highly alliterative, almost leonine line, often proceeding in paired thoughts separated by a breath, is companionable, and commends these poems to a walk. ‘Blousy Guitar’ is exemplary of this style; the lines are of roughly equal weight but the variable tempo corresponds to the rush and distraction of rapidly successive thoughts:

Blousy guitar I don’t want to count the beats Hey Hey

My pen I have bed hair in the best way Daughter

Of sunlight and air and I’m glad you were born

On this day or put another way: that you were

Born Let’s be superstars Let’s call each other “suckas”

Turn everything into writing Lord of my Love

And eat new raw oysters with many condiments

To lord & love to be generally great

The flopping flowers that die in a poem

Summer solstice smacks me in the face ridiculous

And I dream the different like a naked sonnet

Your raw throaty laugh submerged under hot noodles

I wrote “valley” when I meant “longing”

Your laugh a river A trout kind of green (35)

This O’Haran declamation bears upon those improvised rituals comprising friendship; if the time of this poem is the time of a celebration, its frame encompasses both the action of an evening and the accretion of events making an anniversary.

“I don’t want to count the beats,” the poem announces, but it is both rhythmically incessant and rhymes charmingly at angles — Hey Hey in the best way, love with love — self-touching and contained. The near-rhyme of ‘superstars’ and ‘suckas,’ two of the evening’s boastful epithets, establishes the poet-celebrant in laughing company, “to be generally great” of an evening: the sonnet is a form rife for dedication, and this one feels like a gift.

Another crucial feature of Nguyen’s work that does a great deal to complicate the bluffing lightness of ‘personistic’ poetics is its insistence on the grave historical backing against which the luminous detail appears and persists. The found poem has a special status in Nguyen’s work, as does the list. This repurposing is far from the treat-yourself mock-generosity of the serial appropriator, by which I do refer to last decade’s conceptualists; rather, it performs the opposite ethic, acknowledging a debt to facts and preceding representations.

This calls to mind once more the objectivists. Of the many roles one might assign a poem, sharing information is as good as any, Nguyen insists, as demonstrated by the poem ‘Who Was Andrew Jackson?’:

He was the seventh president of the United States

He was responsible for the Indian Removal Act

He was poor but ended up rich

He was an enslaver of men, women, and children

He was given the nickname “Indian killer”

He was put on the twenty-dollar bill (11)

Between the stylistic extremes of the poems quoted here are poems of family and political history, insidiously co-implicated; poems that thwart and perform mythology; love poems, protest poems; a whole surprising book’s worth of (above all) poet’s poems that refuse both easy comfort and despair.