Snapshots: Review of The Negation of Chronology: Imagining Geraldine Moodie, by Rebecca Luce-Kapler

Reviewed by Louise Carson

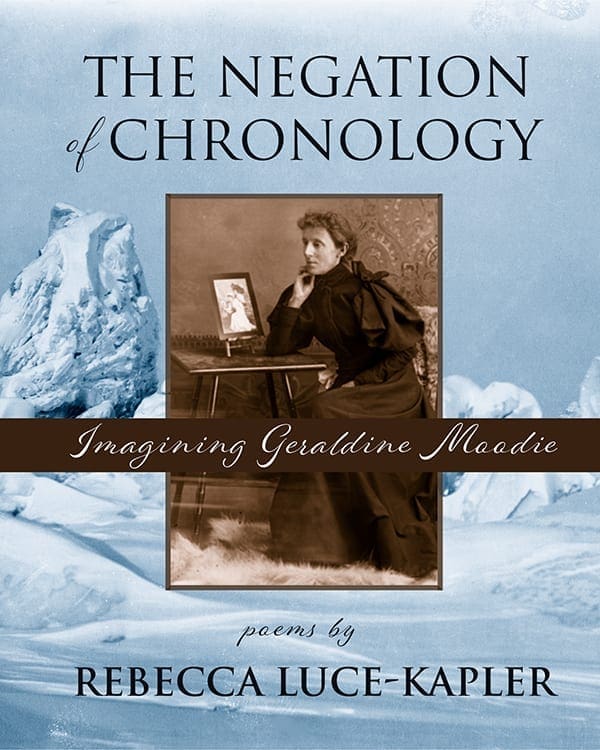

The Negation of Chronology: Imagining Geraldine Moodie, Rebecca Luce-Kapler (Inanna, 2020).

I knew after I’d read the forward, that I’d be interested in the material covered by Rebecca Luce-Kapler in The Negation of Chronology. I’d just finished reading Molly Peacock’s Flower Diary, a biography of American/Canadian painter Mary Hiester Reid (1854-1921), who was of the same generation as Geraldine Moodie (1854-1945). Now for a treatment of a female photographer through the medium of poetry.

As those of you who have read some of my previous reviews may remember, I love history and geography, so the fact that The Negation of Chronology contains photos of and by Moodie in central and western Canada is a bonus. But the poems.

Some of them are dated by the poet, reinforcing the historical context. The first is not and functions as an introduction. ‘Negation’ asks: who was Geraldine Moodie? And the poet replies: “Geraldine Moodie was a woman. / She had bright copper hair, / six children, and a Kodak.” The bare facts.

Moodie also had a husband – John Douglas, or J.D. – whose work as a member of the North-West Mounted Police moved their family eight times in 50 years.

Like photographs, the poems are vignettes, moments in Moodie’s life. But, most of them are completely imagined scenarios, as Luce-Kapler tells us in the book’s title. An interesting note to this book is that Geraldine Moodie’s grandmother was Susanna Moodie, her great-aunt Catherine Parr Trail, and their letters provided insider information for the poems.

In ‘In February of Her Eleventh Year’ Moodie’s father dies and there is “only the grey aftershock, / the tatters of shadow.” This image at the end of the poem contrasts its beginning, when the child on a walk “dawdled in sun sparks of snow, a slow dance of waning winter,”. Then at home, she finds her mother’s grief, her father’s still, suited body on the bed.

In the first 25 years of Moodie’s life she went from Toronto to England to Manitoba. Seeing her husband sod-busting in a dream, destroying the grassland, she wakes, goes out and sketches a wildflower. “When the horizon glows / I fill in details, lit tongues / of colour rising to meet the sun.” (From ‘Wildflower’) She has begun to pay attention, as evidenced by the language in the next poem ‘Bloodlines’. “never having lived where the land / marks were unreadable,” and “even the plenitude of stars / swallowed her in their bowl of light.”

Just prior to these two visually pleasing and personal poems, is the first of two poems with the same title. ‘In the Meantime’ presents the prairie circa 1880 as yet untouched by settlers. “The land is empty.” is the poem’s first line. And Luce-Kapler uses the word “yet” three times, at the end of each of the three verses, as a pointer for the reader to ponder what is coming. One of the outstanding poems in this collection.

The first section of the book is called Camera obscura: Early moments, and the second, Still life: The detachment. Together they cover Moodie’s early years to the point where she begins photography seriously. Part two begins with Moodie colouring in her sketches of plants, a “delicate, deliberate business.” (‘Evening Primrose’) This section closes with ‘The First Self-Portrait’, which ends: “I stop to watch a farmer forking / hay for his cattle, see / the picture, set up the camera / on tripod, dazzling sun behind, / shoot my shadow stretching / across this snowy land / I am soon to be leaving.” Just a shadow, as yet. She’s in Lakefield, Ontario, a place that would be her refuge, and readying to move out west.

Throughout, she and J.D. experience difficulties within their marriage. She leaves the prairies and takes the kids back to Lakefield; after a time, he followed her and they make up. We get the feeling that she is restless, needs the photography as an escape from housework and child-rearing.

Within part two, the poem ‘Intimacy’ stands out. She has a camera and Luce-Kapler tells beautifully the moment of creation, as Moodie searches “for a delicate / thing shining against a backdrop.” “Then I see: sapling maple / showered in an aura.” After that, it’s easy and she takes picture after picture. “The imprint / of my fingers soft / upon the body of the camera.”

Part three, Landscapes: A travelogue, is the longest section of the book, covering most of Moodie’s adult life and work, and here Luce-Kapler chose to place the second poem called ‘In the Meantime’, dated Lakefield, 1891. It includes snapshots of leisure summer moments, a sense of the indigenous culture going underground, and “The story resists shape / even as the clock chimes / in the parlour; light / lengthens and narrows.”

The previous poem of the same name is the same shape – three short verses – and when I re-read it, I was struck by how much more lyric the poet’s images were of the Manitoba prairie, and therefore (if we go along with her imaginings) how much more Moodie was struck by the prairie landscape. It’s an interesting way of showing how Moodie, an easterner, had transitioned to preferring the west. Or had she? Westward, dear reader, ho.

The next 20 poems track Moodie’s life from one posting to another, as she sets up one professional photography studio after another.

She has become aware, not just of the land, but of the indigenous people there. In ‘Watching the Sun Dance’, the two meanings – that she is photographing a sun dance and the sun dance – are clear.

Luce-Kapler uses light, or its absence, to give depth to emotions. In ‘Carried by Light’ J.D. is worried that “the light has carried her away.” And the reverse. In ‘Finding George’, “Since the New Year every photograph is haunted by shadow / in the backdrop.” Their eldest son has died following an accident. Part three ends as the Moodies are posted to the north. Now life is more harsh; she photographs the body of a dead trapper J.D. pulls from the river. Now she takes pictures of Inuit people.

Part four, Time-Lapse: Composing a Life, opens with ‘Negation of Chronology’ and an explanation of the Geoff Dyer quote which opened the book: “Photography, in a way, is the negation of Chronology.” Life is transient, and, as the poet says “Somewhere in the house / a clock keeps ticking.”

Moodie and J.D. are back in Manitoba; they retire. And Luce-Kapler gives us a final poem, ‘The Selkie’, which I read as Moodie’s death-poem, and which is one of the outstanding pieces in the collection. I’d like to quote it in full.

Fields of grain erasing the grasslands

acre by acre until they are lost

to gold ripples in the noon light

and she feels an old tug to flee to the open

clear air lifting her over the harrowed land

while she sails west with the red-tailed hawks

hunting for her true home certain

that she will know when she sees it

even though that too will slip away

a skin for a time that will not stay

even for the next wave of gusts

dark clouds from the mountains

that merge over the flatlands storming

what she thought was easy sailing

-The Selkie

The lack of punctuation makes the poem, when read aloud, resemble those flickers of image and association the brain assembles as it slides into sleep, and, one hopes, not too painfully, dies.

This artistic high point faces a final photograph. “Royal North-West Mounted Police hauling wood to barracks over Churchill River, Manitoba.” ca. 1906-1909. It’s wonderful. A husky team pulling a small sled piled with wood comes sideways at us, the dogs’ mouths open, tails curled tight to their bodies.

I felt a shift away from Moodie’s personal life with its sorrows, frustrations and compromises. My perception of her zoomed out, as it were, as I realized that this woman contributed to the historical documentation of this country in a concrete way. “Fields of grain erasing the grasslands… / what she thought was easy sailing”.

The Negation of Chronology: Imagining Geraldine Moodie, Rebecca Luce-Kapler (Inanna, 2020).

Louise Carson has published two books of poetry – Dog Poems, Aeolus House, 2020; and A Clearing, Signature Editions, 2015. Her poems have twice been selected for Best Canadian Poetry, in 2013 and 2021. She also writes mysteries and historical fiction. She lives near Montreal.