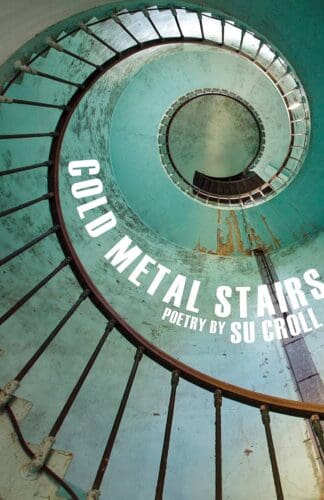

Review: Cold Metal Stairs by Su Croll

Reviewed by Marguerite Pigeon

Dementia might seem like the anti-muse: not creative inspiration, but its sapping. Yet, in her new collection, Cold Metal Stairs, Su Croll follows dementia—her father’s—as it pulls her vicariously, clanging and spiralling downwards, through grief, fragmentation, and fear.

Dementia might seem like the anti-muse: not creative inspiration, but its sapping. Yet, in her new collection, Cold Metal Stairs, Su Croll follows dementia—her father’s—as it pulls her vicariously, clanging and spiralling downwards, through grief, fragmentation, and fear.

The poems in this collection enact the repetitive, temporally confusing stretch during which a parent loses memory and, eventually, life, to dementia. The tone throughout is immediate. Croll uses clear language, repeated phrasing, and sometimes dense narrative-block stanzas to capture the cold facets of experience. There are panicked, staccato questions, as in “Gone”: “Where is my father? Where has he gone? Did he disperse? Did he disappear into the raw density of air?” There is grasping at better times in the face of complications related to the illness, such as pneumonia, as in “His Voice that Remains”: “My father’s voice teacher trained him to fill the air of a room with/music, to breath through a song and trust his lungs to do/their work.” More painfully, there is an admission of the wish for the dementia to end, as in “Wanting the Call”: “I want the phone/to ring out and free us/from being inside/the dying with him.”

While the poems too are tightly bound to this dying, Croll offers glimpses into the rich life that came before, including her father’s career as an arborist. Indeed, she frequently evokes the imagery of water, air, and trees as a means of grounding complex concepts. Memory becomes “…the movement of leaves overhead,/shushing in the breeze,” death “the black/ closed-off forest,” while trees analogize the exchange of air that supports life. This in-and-out movement is key to the book’s overall intention: Croll is on a quest to understand her father’s life and death—two “tick-tocking branches” of the same tree.

At times, she explicitly tussles with the ethics of her project. Should she be writing about her family’s most personal tragedy? The answer arrives in the poem “Speech Acts” with a ferocity that reminds us how desperately a poet is needed when events need processing, even when that poet is one and the same person as the sufferer:

The slick shadowed black spill;

the derailment, the broken

mechanism of his death (my father’s

death is obscured and I want

someone to interpret it using clean

clear, water powered utterances.

Croll has answered her own call to record, interpret, and clarify. So closely does she acquaint us with the pain of dementia that we squirm and even wish, like her, for an end. But to remain with Croll until the final pages of Cold Metal Stairs is to appreciate her courage. Because this is where she addresses the months, then years following her father’s passing in poems that announce a return from the dark passages of grief. Croll’s muse wasn’t dementia after all, we learn, but rather, its comingling of being and not being. It’s a dialectic that universalizes the poems in Cold Metal Stairs and makes them vital.