There’s Art In Dying: a Review of Uncharted by Sabyasachi Nag

Reviewed by Josie Di Sciascio-Andrews

Sabyasachi Nag. Uncharted. Toronto, Ontario: Mansfield Press, 2020.

Whether in the animal kingdom or amongst humans as a metaphorical prodigy, a white tiger is a rare, ferocious wonder, born only once in a blue moon or a century. Such is the pervasive impression that lingers in us after reading Sabyasachi Nag’s Uncharted. The title opens up a topology of unexpected, varied offerings of griefs and delights inherent in ordinary days. The poet shoulders the enormity of synthesizing a world uniquely perceived and expressed through an unparalleled propensity for observation and a felicitous use of language and metaphor.

Whether in the animal kingdom or amongst humans as a metaphorical prodigy, a white tiger is a rare, ferocious wonder, born only once in a blue moon or a century. Such is the pervasive impression that lingers in us after reading Sabyasachi Nag’s Uncharted. The title opens up a topology of unexpected, varied offerings of griefs and delights inherent in ordinary days. The poet shoulders the enormity of synthesizing a world uniquely perceived and expressed through an unparalleled propensity for observation and a felicitous use of language and metaphor.

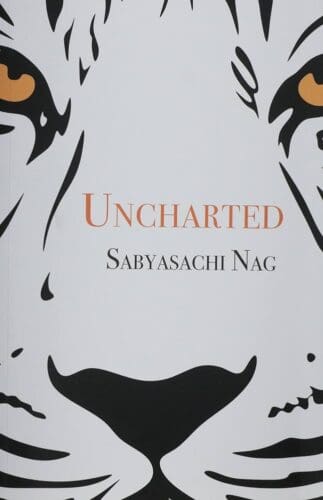

When I write a poetry review, in order to do the work justice, it takes me a long time to reflect on the poet’s words, to inhabit their landscapes and to immerse myself in the meanings of each piece, as it relates to the collection. At first sight, the cover of Uncharted took me back to Yann Martel’s The Life of Pi, albeit a zoomed in, white, up close and personal version of it. Pi, synchronistically my nickname from when I was a child. In its synergy of image and words, this book led me back to the solipsism of my life. As they say, every review is as much about the book being studied as it is about the reviewer. It follows that the observed work is entangled therefore, with my own perception and essence. This is a book of poetry about life, the life of me or you as the reader of it, our own.

On the soft to the touch cover, our eyes are locked in by the hypnotic gaze of a white tiger. In meditating on the image, we discover suddenly to be face to face with an animal that is beautiful yet dangerous: a divine, wild animal that awakens our awe and our ultimate primal fears. Like the rarity of a true poetic voice, it comes along only once in a lifetime. We enter the eyes of the tiger we hold in our hands in the guise of a poetry book, in the uncharted territory of life and death, much like we unknowingly do every moment we are alive. This is all real and not a simulation. There is no chance to escape. We will not make it out unscathed.

Sabyasachi Nag’s poetry is sublime. In reading and re-reading each poem, I found myself lost in the vistas and characters his words paint. The collection is divided in three sections: identity, belonging and death. Much like the life of any human being, or the proverbial Pi, it begins with the id/ego formation, then moves through a life of gathering experiences, connections and some sort of hypothetical meaning, finally arriving at the last milestone of mortality. Just like a man’s existence is itself unexplored, Nag’s poems leave us with questions rather than answers. We are led to myriad moments and places without maps, the territory unknown, a step by step journey that reveals itself only in the moment each step is taken.

The poems in the identity section ask many questions: how does one grow roots? What does one know of arrivals? What do we leave when we leave home? How much further from home before we have truly arrived? Departed? How does one know what to follow? When is it too late to turn around? As in reality, there is no true answer, but the beauty or the horror of the voyage. In A Father’s Reflection Upon Naming A Child, we read: before there was a mirror, before map and compass, before the ship of Theseus, before language and arithmetic, go ask the ants what name they gave their song. Also, in the poem How To Interpret A Dream, dexterity of language unfolds the ominous loveliness of a predator consuming its prey: death and beauty in one view. As the jar tipped, the Goldfish danced itself to death and the Octopus appeared from nowhere, stretching itself, past the scattered glass; stretching into a river inside a locked room, bleeding where the sun scraped the skin, because a room is no place for a river octopus, floating like a sea anemone, shiny, colourless, shifting, weightless even though it was gathering in places metaphors way outside its own weight, and because it happened really quickly, like an ancient apparition, you know, not from seeing, but instinct -it had to be preserved here, in the book of passage and erasures.

This is poetry I recognize, as if the words were the mica of my own bones: the reasoning, the temple, the stage, God, the golden rule, the rot, the language spoken in multiple tongues, the dwarfs in alien systems, Eugenics, Ovid, lake Ontario, the glass reliquary of some saint watching her own flesh grow inside a vase, the blood stained pixels floating in farce. As we inch along each poem, the uncharted-ness of living becomes even more relevant as the poet likens it to a sky where fractals of dead stars have left in their wake signs of being. For some, the poet writes, nothing can scare them out of their gold trappings, while others have quietly yielded, as they burn as though they had something important to prove, pass on, more than fear or revenge, meaning. What meaning can we construct however, out of our voyage from birth to death?

What I love about this collection most, is the continuous uncertainty of the human in the face of the unknown in the journey through reality. Have you ever looked at moth wings splayed on wild bindweed? What does that mean? Or, what do we talk about when we talk about death? We get no closer to knowing the truth of anything as we approach the end of the book or the end of our lives. We are no wiser for the exploration or the words or our days, in spite of their gorgeous eloquence and stolen shards of happiness. In the final moments, barely lucid, our senses slipping, we ache to reach the limit, as if it were a sign of a fresh start, when we are left with an aftertaste and a craving, a craving for more poems, a craving for more life.

Indeed, after reading and re-reading Sabyasachi Nag’s Uncharted, I was left longing for more. This is a fine young poet to watch for. His skilled mastery at cohering words and lines from many sources of influence is spellbinding. Inspired by the work of many, among which C.D. Wright; edited by Stuart Ross and published by Denis De Klerck, Uncharted is available from Mansfield Press, Amazon and bookstores worldwide.

Sabyasachi Nag. Uncharted. Toronto, Ontario: Mansfield Press, 2020.

Josie Di Sciascio-Andrews is a poet, author, teacher and the host & coordinator of the Oakville Literary Cafe Series. Her latest book of poems, Meta Stasis, was released July 2021 by Mosaic Press. Her collection of local poems and photography, Sunrise Over Lake Ontario, was launched in 2019. Her previous poetry publications include: Sea Glass, The Whispers of Stones, The Red Accordion, Letters from the Singularity and A Jar of Fireflies. Josie’s poetry has been shortlisted for the Malahat Review’s Open Season Award, Descant’s Winston Collins Prize, The Canada Literary Review, The Eden Mills Literary Contest and The Henry Drummond Poetry Prize. Her poetry has won first place in Arborealis Anthology Contest of The Ontario Poetry Society and in Big Pond Rumours Literary E-Zine. Some of her poems feature on The Niagara Falls Poetry website. One of her pieces was included by Priscila Uppal in Another Dysfunctional Cancer Poem Anthology, Mansfield Press, in 2018, rated by Chatelaine Magazine as one of the best Canadian poetry books of 2018. Josie is the author of two non-fiction books: How the Italians Created Canada (the contribution of Italians to the Canadian socio-historical landscape) and In the Name of Hockey ( a closer look at emotional abuse in boys’ sports.) Josie teaches workshops for Poetry in Voice and for Oakville Galleries. She writes and lives in Oakville, Ontario.

Sabyasachi Nag (Sachi) is the author of two previous collections of poetry: Bloodlines (Writers Workshop, 2006) and Could You Please, Please Stop Singing (Mosaic Press, 2015). He is a graduate of the Writer’s Studio at Simon Fraser University and Humber School for Writers. He lives in Mississauga, Ontario.