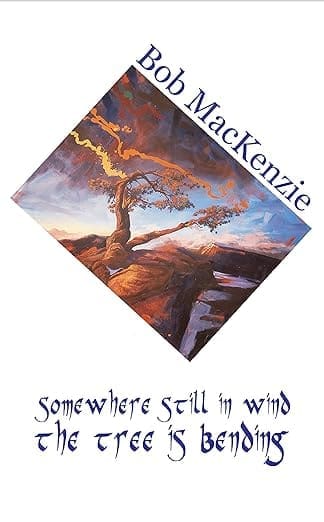

Trying to be the tree: a review of somewhere still in wind the tree is bending by Bob MacKenzie

Reviewed by Louise Carson

somewhere still in wind the tree is bending

Silver Bow Publishing, 2018

82 pages, $20.00

ISBN: 9781927616758

The tree is on the front cover, a weathered and twisted bonsai-shaped thing, growing out of rock. The title slows me right down; is why I chose to review the book. And you know, at this time of year, I really need to slow down, as temperatures veer from cold, near-frost nights to heat-wave days. Makes sowing and planting a bit of a guessing game. Trying to be the tree, somewhere still.

MacKenzie opens the book with that quote from Omar Khayyám about the moving finger – fate. And I guess those words tie in to the title words about bending but not breaking under adversity – and how the adversity is coming (or already has) into each life. The poem the title line comes from – ‘Pyramid’ – describes how humans moved from sticks to machines to all-out war. How timely for we readers, as the Ukrainian spring slips into a Ukrainian summer. The poet asks “who can name this dancer” and at the end, out from the shadow of near-total destruction, a human begins to rebuild another pile of sticks. Greed and its ramifications.

There are other poems of war, of a world ending, of something ending. ‘traveller’ brings us to a funeral for communism. Here are the last four lines.

grey men stand around a hole in the earth

tossing in handfuls of forgotten dreams,

manifestos, and songs, then silence comes

somewhere near the edge an old woman weeps

Women do a lot of weeping in these poems. MacKenzie’s women are mostly old, or otherwise used up; young and damaged. A woman in the rain; in a bar; selling artificial flowers in the street; committing post-trauma suicide – all broken. From ‘photograph’ “in the shadows / an empty gown”. In ‘and I will dance’ the woman upstairs plays her music loud enough to be heard outside where kids are playing, and she chants defiantly “I will bring over all the neighbour children / and I will dance”, a hopeful if probably doomed ambition.

The book opens with a few poems about words and writing. In ‘meeting’ MacKenzie begins with “there are poems / outside / what I write” and towards the end says “the safe refrain / from unknown forms / words don’t do”. And in ‘the words are not the same’, words are only one of the ways people try to communicate.

The poem ‘read aloud’ declares in its first line that “the words don’t matter”. Obviously, they do, but the poet seems to want to break the clichés of “the moving finger writes” and “in the beginning” by inserting little word sequences like “caress warm savage rush” or “dance fire smoke captive”. Interesting. Actions, not words. And it is in the poems where this imaginative device is used that MacKenzie’s words come alive.

These lines from ‘Kaleidoscope’

Sky purple yellow night rainbower

growing jade raspberry stone-grey still

and later

Kodak raindrop feathers shower now

are stimulating.

One poem in particular stood out as being strange and rich – ‘Scarred’.

I have held the rim’s curve,

fingertipping,

and have hung so, wheelbound,

fasterclipping,

peered beyond my fingers,

spied the scarmarks

on the other side’s face,

painted starsparks

and moons of blue and dead.

Come now, come late,

I have held this rim’s curve –

this paper plate.

Like the tree, somewhere still the poet is bending.

Louise Carson has published two books of poetry – Dog Poems, Aeolus House, 2020; and A Clearing, Signature Editions, 2015. Her poems have twice been selected for Best Canadian Poetry, in 2013 and 2021. She also writes mysteries and historical fiction. She lives near Montreal.