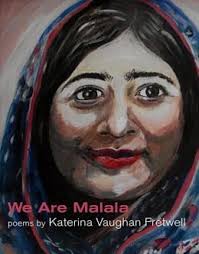

Review: We Are Malala: poems and art by Katerina Vaughan Fretwell

Review by Penn Kemp

A Canadian artist muses on Malala Yousafzai in poetic dialogue

Katerina Vaughan Fretwell, We Are Malala: poems and art. Inanna Press

“We realize the importance of our voices only when we are silenced.”

—Malala Yousafzai

On the day I read Katerina Vaughan Fretwell’s We Are Malala, a photo appears on my screen’s feed: Malala Yousafzai meets youth activist Greta Thunberg for the first time. Malala and Greta become instant fast friends, and no wonder. Both young women have addressed the United Nations on their respective causes (climate change and girl’s education). When Malala was 17, she won the Nobel Peace Prize. Herself now 17, Greta too has been nominated for this high honour. Malala posts the two them, arms around one other. Her caption reads: “Thank you, @gretathunberg” along with a heart emoji.

On the day I read Katerina Vaughan Fretwell’s We Are Malala, a photo appears on my screen’s feed: Malala Yousafzai meets youth activist Greta Thunberg for the first time. Malala and Greta become instant fast friends, and no wonder. Both young women have addressed the United Nations on their respective causes (climate change and girl’s education). When Malala was 17, she won the Nobel Peace Prize. Herself now 17, Greta too has been nominated for this high honour. Malala posts the two them, arms around one other. Her caption reads: “Thank you, @gretathunberg” along with a heart emoji.

CNN reports on the meeting of the world’s two most renowned young activists:

Greta Thunberg visited Malala Yousafzai at the University of Oxford, where the Pakistani activist is a senior. Thunberg is in the UK for a school strike planned for later this week.

Admiration between the two activists was mutual.

“So … today I met my role model,” Thunberg tweeted. “What else can I say?”

“She’s the only friend I’d skip school for,” Yousafzai quipped.*

The dialogue between these young women drew me back to Katerina Vaughan Fretwell’s We Are Malala: poems and art. The connection is appropriate because Fretwell creates a similar evocation of female friendship: hers is by proxy, through the media. Her collection of poems sets up a dialogue between Malala and Fretwell’s own personal history, though the two have never met. Fretwell intertwines her stories with the large context of Malala’s. How do their stories connect, as young women growing up in different times, different continents? What are the disconnects? Fretwell’s education as a girl is assured in ways that Malala’s never was, but as Fretwell succinctly displays, the similarities of female disempowerment are shocking, despite the poet’s apparent privilege.

It’s essential for women to tell their stories in whatever form best suits. Fretwell’s primary medium is poetry— breathless poems in short lines, reminiscent of the Urdu poetry that Malala might recognize. The poems form an urgent inquiry that Fretwell and Malala share. How does a young woman adapt to the culture in which she was raised? How can she change the culture in which she is immersed? Both Malala and Fretwell leave their country of birth, for another, safer, saner place. Malala’s exile is involuntary: after the gunshot wound that nearly killed her, she awoke to emergency treatment in Birmingham, England. Fretwell in political protest left the U.S. for Canada, where she still (proudly) resides.

Political poetry is difficult to write because it all too easily swerves into didactic, self-righteous polemics. A good poem follows sound and language itself, leading both the poet and the reader/listener into new and surprising exploration. A political poem tends toward rant, set on the rigid track of a pre-conceived idea or conviction that the poem must adhere to. Political poetry can be written as reaction, in the moment. It has the energy of immediacy, but often it has not had time to cure/ mellow age with a wider perspective. Political poetry is often undigested emotion that has not been realized as art.

In his Preface to Lyrical Ballads, William Wordsworth writes that “poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquility: the emotion is contemplated till, by a species of reaction, the tranquility gradually disappears, and an emotion, kindred to that which was before the subject of contemplation, is gradually produced, and does itself actually exist in the mind”.

Malala Yousafzai’s history is so moving that our immediate response of empathy and horror can become sentimentally ineffectual. Katerina Fretwell has taken the time necessary to allow emotion to settle into contemplation, into poems that move the reader into wider perspective of understanding that deepens our response. In We Are Malala, Katerina Fretwell walks a fine line, escaping the trap and sensationalized trappings to explore a wider perspective than her personal narrative. The dialectic between poet and her muse continues. These poems stir the reader into action.

But how do we continue activism while we study or pursue our chosen art? How do we manifest that art in action? Fretwell points a way. Her enthusiasm, her passion, ignites and inspires. And Fretwell has several bows in her quiver. Not only is she a widely published and accomplished

poet, but she paints as well. The artwork included in this volume features paintings based on photos of Malala Yousafzai. Fretwell adeptly capture’s unflinching spirit. She brings Malala to life on the page in striking reds and greys. Malala’s eyes dominate, demanding that you engage, that you pay attention. The paintings pay tribute and reflect their counterparts on the page. Readers, take note.

Malala,

this verse serves me well:

…So vie with one another in good works

As always, Inanna’s production values are impeccable, so that the font is easy on the eye, the pages sturdy and Fretwell’s art work subtle and powerful in reflecting the poems.

One of the best editors of our time, Harold Rhenisch, is acknowledged, “non pareil”, as pulling the poet out of the politics and into the poetry: an essential task, this conversion from reportage. News, undigested, is unlikely to stay new. To endure, it must be transformed into art. In William Carlos Williams’s famous line, “It is difficult/ to get the news from poems/ yet men die miserably every day/ for lack// of what is found there” And to Ezra Pound, “Poetry is news that stays news”

Reactions to “ecological grief” and “climate depression” are given form in these poems and by their expression, that grief, no matter how bleak is alleviated in the very act of creation. As Malala writes, “When the whole world is silent, even one voice becomes powerful.” Fretwell joins the chorus of women speaking their many truths. “One child, one teacher, one book, one pen can change the world.” At this perilous time, we need artists to tell their histories and to inspire and encourage transformative change.

Like Henry Vaughan, her poetic and literal ancestor from the seventeenth century, Fretwell contemplates “The World”. Vaughan writes, in his famous poem of the same name:

Time in hours, days, years,

Driv’n by the spheres

Like a vast shadow mov’d; in which the world

And all her train were hurl’d…

The darksome statesman hung with weights and woe,

Like a thick midnight-fog mov’d there so slow,

He did not stay, nor go;

Condemning thoughts (like sad eclipses) scowl

Upon his soul,

And clouds of crying witnesses without

Pursued him with one shout. **

Fretwell too, takes on the world. Her “clouds of crying witnesses” are young women activists in hot pursuit of injustice. They are intent on holding “the darksome stateman”, in all his guises, to account.

Some of Fretwell’s phrases will ring in your head long after you have put the book down. My favourite lines in the book link spirit and the natural world:

Once all women could talk to trees. *

I still chant to forests, seeing chi—

silvery energy—pulsing around twig,

leaf, branch, bole. The whole.

The last lines of this book are a rallying call:

United we thrive, divided we die.

All souls. All sentience.

Sentenced to prescience, We Are Malala.

* Link

** Link