MEET THE SHORTLIST: RACHEL ROSE & DEREK WEBSTER

For the third installation of our 2016 “Meet the Shortlist” blog series, we meet Rachel Rose, whose book Marry & Burn was shortlisted for the Pat Lowther Memorial Award, and Derek Webster, whose book Mockingbird was shortlisted for the Gerald Lampert Memorial Award!

Throughout National Poetry Month, we’re excited to introduce you to all the poets shortlisted for our book awards: the women shortlisted for our Pat Lowther Memorial Award, the new poets shortlisted for the Gerald Lampert Memorial Award, and the League members shortlisted for our Raymond Souster Award. The winners of these awards will be announced on Saturday, June 18 at a special awards luncheon at the Canadian Writers’ Summit. Find a complete shortlist for all of our awards here.

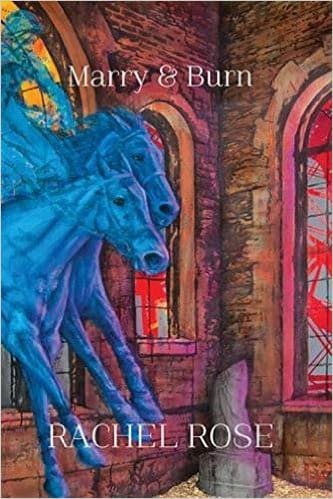

RACHEL ROSE, Marry & Burn

Recently a fellow at The University of Iowa’s International Writing Program (IWP 2015), Rachel Rose is the Poet Laureate of Vancouver for 2014-2017. She has published work in journals and anthologies in Canada, the U.S., New Zealand and Japan. A chapbook, Thirteen Ways of Looking at CanLit, (Book*hug) and her fourth poetry collection, Marry & Burn (Harbour) were both published in 2015. Her non-fiction book, Gone to the Dogs: Riding Shotgun with K9 Cops, is forthcoming from St. Martin’s Press in 2017.

What was your favourite part of writing this book?

Turning a difficult life transition into fuel for certain poems; looking back from a different, and happier, vantage point. Also, working with Harbour Publishing has been a delight. They’ve published my last two books, and the whole Harbour team has been both dedicated and supportive. Working with a great press makes all the difference, every step of the way.

What was the hardest part?

Writing these poems was challenging, but it was not hard; it was a deep, effortful pleasure. Each poem demanded different approaches, as I found the subject matter, the form, the voice. I was concurrently writing a memoir about my time riding along with police and their dogs, and sustaining that narrative has been harder. It is good to be able to write poems while writing prose. It refreshes. Each poem can be contained on its own, unlike prose; each one can be its own small world, created and complete in a relatively short period of time.

Where did you spend most of your time writing?

I am a wanderer and a scribbler. I walk and compose, take notes, or carry images home in my mind, then type them up and then begin the endless process of revision. Movement helps me think and write better. That is why I bought a used treadmill and created a treadmill desk for myself. I move very slowly on it, and the motion quiets a restless within so that I can work. (Though there is a certain point in the work where I must stop and be very still). Most of the time, I’m highly distractible and sensitive to noise. But when I’m deep in revision, I am the opposite of stuck. When I’m in the zone, everything flows freely and it doesn’t matter where I am or what other distractions are around me. I can work while one of my kids is three feet away, pounding on the piano. But there’s always resistance and slogging to get to that place of flow, of pure creative energy. It helps to expect resistance.

What were three major Canadian influences on this book? Literary or otherwise.

I don’t think in those terms. That is, my books are influenced by all I am reading, or have read, and I read as widely as possible, across time and culture. Of course I am influenced by Canadian literature, by Alice Munro’s stories, by the poems of Michael Ondaatje and P.K. Page, Sharon Thesen, Lisa Robertson, Lorna Crozier and Alison Pick, to name a few, but I never read for national pride, only for personal pleasure or growth. This book was influenced by the information that was emerging about residential schools, and the challenge that knowledge of these facts posed to Canadian identity—what the reality was as opposed to the comforting myth.

Who is one up-and-coming writer you think everyone should start reading right away?

Well, Ann Dowsett Johnston is not an up-and-coming writer in some ways, because she’s had such an accomplished career. But I am choosing her first book, Drink: The Intimate Relationship Between Women and Alcohol, because it’s a book I’d like everyone to read. We need to be having these conversations about women and alcohol, which in turn are conversations about sexual assault and consent, about feminism, and about addiction. Her book is important, it’s brave, and in its pages she allows herself to be vulnerable in ways that can teach us all. I also love Sarah Leavitt’s graphic novel Tangles: A Story about Alzheimer’s, My Mother and Me. Even those these books couldn’t be more different, I think I like that they both teach me new ways of seeing and thinking. Now, whenever I chop vegetables, I try to use my right hand (I’m left-handed) and I think of Tangles, and love, and illness and willpower and fate and family—all those tangles.

—-

DEREK WEBSTER, Mockingbird

Derek Webster grew up in Beijing, Toronto and London. He received an MFA in Poetry from Washington University in St. Louis and is the founding editor of Maisonneuve magazine. His poetry and prose have appeared in Boston Review, Pleiades, BOMB, Partisan, The New Quarterly, The Malahat Review, The Walrus and elsewhere.

What was your favourite part of writing this book?

Writing poems for me is sort of exquisite torture, so really, working with award-winning designer David Drummond on the book’s cover was the most enjoyable part. David has created a stark, enigmatic cover: a coat hanger with a hooked beak, some torn paper (or is it a shroud?), a background that I like to call Underworld Black… it all sets the right tone for the poems inside. Working with a virtuoso like David is one of the perks of working with Véhicule Press..

What was the hardest part?

I think continuing to believe in myself, over the years, was the hardest part of producing Mockingbird. Many of these poems have been 15-20 years in the making, so as I wrote new poems and looked back at old ones, and rejections of the manuscript piled up, I wasn’t at all convinced that what I was doing was worthwhile. I had to work pretty hard to shut out my inner critic and keep writing.

Where did you spend most of your time writing?

I wrote these poems on College Street in Toronto; as a grad student in St. Louis, Missouri; at my family’s cottage in North Hatley, Quebec; and a dozen apartments and homes in Montreal that I’ve lived in over the past 25 years. But I guess it all came together in the last 3-4 years around the kitchen table in Mile End, where I live now.

What helps you write better? What creates roadblocks?

Reading good poems by my fellow poets helps—people like James Arthur, Linda Besner, Jeremy Dodds, James Pollock, Karen Solie, Nick Thran… the list goes on. There are a staggering number of good young poets in Canada today. It’s very encouraging.

When I’m writing, music is a problem for me, because it tends to block out the (subtler, more fragile) music of the words.

What were three major Canadian influences on this book? Literary or otherwise.

Anne Carson — her concision and ability to create searingly well-turned phrases are a challenge and inspiration to me.

F. R. Scott — I started reading Frank Scott decades ago, and although my estimation of his poetry has changed over the years, the sense of kinship and inspiration I get when I think about him has not. He understood that Canadian artists had to be both Canadian and international, loyal to the local as well as engaged in a search beyond our borders for something new.

I suppose, also, just the basic Canadian condition of long, dark winters, a body of water nearby or through trees, and the upheaval of changing seasons.

What’s next?

A book of essays about poetry and another book of poems.