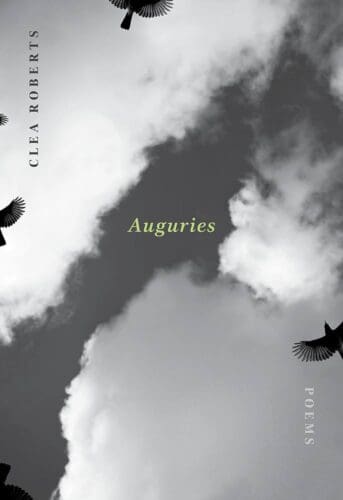

Review: Auguries | By Clea Roberts

Brick Books | 2017 | 104 Page | $20.00 | Purchase online

Signs, Signals, Divinations: Clea Roberts’ Auguries

Review by Susan McCaslin

Review by Susan McCaslin

Clea Roberts’ spare, finely-crafted Auguries (Brick Books, 2017) is, as the title suggests, a scanning of the Yukon sky and landscape for signs and portents of mysteries both hidden and revealed. Grounded in the Whitehorse area, Roberts acts as augur, like diviners in ancient times said to have had the wisdom to observe and interpret the flight patterns of birds. Her title invokes another celebrator of revelatory signs, William Blake, who sings in Auguries of Innocence of the poetic-prophetic capacity to see “a world in a grain of sand / And a heaven in a wild flower.”

Not only are these poems burgeoning with ravens, larches, juncos, sparrows, and other species of birds, but images, traces of birds sweep, soar, linger in the margins and blank pages of the book, disappearing and arriving just as they do in the liminal places of everyday awareness. The rests and silences offered by the empty or almost-empty pages scattered throughout the book illuminate how Roberts’ poetry is a dialogue between speech and silence. Within this this cold, haunting northern landscape birds become metaphoric “strings of beads” (“Spring Snowfall, Melting”) and even potential “alphabets.”

…the cranes kettle

always on the verge

of an alphabet…

(“Mountain Walking”)

In an April 2017 interview, Roberts comments on the grey jays at play in the book’s margins:

I’m always looking up at the sky. I love watching birds. Birds are full of poetry. I have a particular fascination with corvids (the bird family that includes ravens, crows, magpies, and jays, to name a few). They are always doing or saying something interesting. They are so common and yet so remarkable. In case you are wondering, those are grey jays (also known as camp robbers or whiskey jacks) on the cover of my book.” (News and Interviews: On Writing, with Clea Roberts)

Roberts is a poet of deep musicality, a lyric poet. The title of the opening poem, “Andante Grazioso,” references a musical notation indicating, “at a walking pace, gracefully.” Here the poet speaks of the playful/ raucous and sacred aspects of the Zen-trickster raven and declares her reason for speaking as a poet:

I’ve decided to speak,

to release certainty

to take winter’s ravens

as my rowdy clerics.

Readers too are invited to “release certainty,” to open to the humility of unknowing. As active participants in the process, readers may become augurs, interpreters of the ineffable particularities of the natural world that interprets us. In “Mountain Walking,” ravens infuse the unconscious: “These early mornings / ravens dismantle // my dreams.…”

Roberts’ grounding in her northern landscape allows her to interweave the personal, domestic and quotidian with the mythic and cosmic, creating a sense of everything flowing in and out of everything else. Her musical lines, with their intuitively precise line breaks, prove that the apparent simplicity, depth, and purity of the lyric voice is still capable of holding the tensions of apparent opposites, life and death, joy and grief in an inclusive whole. In “Heat Wave,”

The thrushes sing

arias to dusk

and displacement.

Here, the light of the night sky appears to humans who “mow the lawns” as “apocalyptic” with “a terrible / orange sun….” Yet the reality of constant change and the inevitable “displacement” of all things through change and death is tempered by the thrushes’ ability to “sing to dusk,” to sing the beauty of the present moment. The reader is left to ask whether the “displacement” of all mortal things might also contain the possibility of renewal or return as in the seasonal cycles. However, the poems do not leave us with theological or metaphysical certainties, but with “arias” to the mysteries.

Auguries not only explores the natural world, but places the speaker’s interpersonal relationships with her partner, child, and mother in the ecosystems of the more inclusive reality that is nature. On a cold morning she transports us to the kitchen where her husband is making breakfast. She proposes,

Let’s be an

old couple

someday

the visible

and the invisible

economies drifting

between us. (“Cold Snap”)

The word “economies” can be read here in its older sense of the Greek term “oikos,” the larger “household of earth” that contains and sustains all our human checks and balances. In our intimate relationships, she suggests, we “drift” between visible and invisible realities. The quotidian world she describes contains “chainsaws” and “a freezer full / of moose,” framed by the nocturnal cries of wolves. The speaker and her partner’s lives straddle the domestic and the wild.

The metaphor of sewing and stitching appears throughout the volume in both domestic and natural contexts to suggest how the two domains are intimately related” “We felt dizzy and foolish, / the shadows unstitched/ from our heels” (“Whiteout, Skagway Summit”). Similarly, Roberts uses sewing imagery when reflecting on the lives of her parents:

They made it through

to spring that way, duty

sewn into them like a

button… (“Getting Wood”)

Roberts’ integration of the personal and the quotidian encompasses both the birth of her daughter Linnaea and the death of her mother, events which occurred within close proximity to each other. Joy and loss collide. The extended suite of poems, “Letter to My Daughter,” is one of the most poignant poems in the collection, beginning with her daughter Linnea’s in-utero existence where again birds enter: “The cries of migrating geese / trigger your kicks” (“Autumn Equinox, Second Trimester”). Then it proceeds through to birth and nursing: “Here’s to the fierce / / petal of your tongue / drawing down the milk” (“Linnaea Borealis”). “Berry Picking” speaks of her love for her child as “[a] love so big / I can only own / a piece of it.”

A daughter comes, a mother goes away: life cycles pass each other. Roberts comments on these twinned experiences in an interview:

During the course of writing these poems, I became a parent and I lost a parent. Through both of these experiences, I came to realize that poetry was a form of expression I consistently turned to when processing joy and grief (two states that are really just different sides of the same coin). (http://open-book.ca/News/On-Writing-with-Clea-Roberts)

Several sequences about her mother explore memory, grief, and release. “Johnson Lake, Late August” ends with the lucent “Musica Universalis,” which restores the allusions to music that inform much of the book. Her mother’s habit of composting becomes in the poem a metaphor for the circlings of life and death that exude a universal music:

and every evening,

she takes a pail

down to the mysterious compost

just as the air

begins to cool

and the weight of dusk

presses down

into the soil,

releasing a scent

that is more of a refrain –

sweet and drifting,

uncontainable.

The sense of music issuing out of death and decay again relocates the high lyric voice in the ground of both the domestic and the wild.

The second to last poem in the book, “Morning Practice,” presents the practice of yoga as integrative body work, extending the traditional yoga postures like “Child Pose” and “Corpse Pose” to include more unconventional ones like “Mountain Pose,” “Half Moon Pose,” “Wild Thing Pose,” and “Fire Log Pose.” Following on the poems about loss and grief, these suggest the need for a spiritual practice involving body work that enables the practitioner to dwell in the present moment in a state of mindfulness, to come to terms with “what the years / have written on your body: / / that you are hard enough / to rise up, and soft / / enough to erode.” (“Mountain Pose”) Again, these postures have their origins in the natural world and tie to the nature imagery of the previous sections.

Auguries ends with a love poem addressed to the poet’s partner and is a return to the celebration of the intimacies of partnership. In “Perseids,” a man and a woman connect to the earth and the night sky as they camp together by a fire viewing a meteor shower. We are left with the sense that, even in the “burning out” of meteors, the rising of pieces of ash from the fire, beauty and vastness still have the capacity to evoke awe.

and everywhere

meteors shooting across

the night sky,

burning out

in the atmosphere

above us, our eyes

blinking, soft,

returned

to amazement.