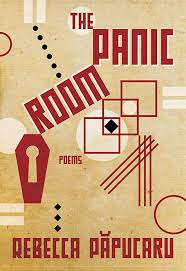

REVIEW: THE PANIC ROOM | BY REBECCA PAPUCARU

Nightwood Editions | 2017 | 96 Page | $18.95 | Purchase online

The Prodigal Daughter’s Return to Memory: Review by Diana Manole

The Prodigal Daughter’s Return to Memory: Review by Diana Manole

Our shared Romanian cultural background has instantly attracted me to The Panic Room (Nightwood Editions, 2017), Rebecca Păpucaru’s debut collection of poems. I was keen to find out how a second-generation Jewish-Romanian-Canadian related to the Eastern European birthplace of her parents. The very first and excellent poem, “My Anne,” surpassed my expectations with its direct references to Dadaism, Brâncuşi, and the Black Sea. Beyond that, I also recognized the fascination words hold for a multilingual individual and the longing a displaced person has for a now-out-of-reach culture. My feeling of familiarity was further deepened by the perception of hybrid exilic and/or diasporic identities as both enriching and alienating, paralleled by the unceasing compulsion to translate oneself:

I’m monosyllabic, dark, not some cobbler of laced felt

slippers prized by Black Sea rustics. These days

I’m the right age for childish word games. Barbara, Greek,meaning strange; Anne, Hebrew, grace. Eleven words, loosely

translated: My grace lies in my strangeness to you, and to me.(“My Anne”)

Yet, the Romanian heritage is only a distant thought in the collection. Most of Păpucaru’s poems focus on her Jewish identity and legacy, but with an attitude that resembles Anne Rothe’s appeal to decency in her Popular Trauma Culture: Selling the Pain of Others in the Mass Media. “Prague Fugue,” for example, reads like an emotional survey of Jewish relics, some from the nineteenth century, others from the Second World War, showcased in a museum, only to end with the indictment of the hypocritical commodification of discrimination, oppression, and genocide:

This is Holocaust industry, this anthem

composed for typewriter and index card.

Jews, are these your musicians?(“Prague Fugue”)

Like other writers who indict genocide from an ethical perspective, such as Lawrence Hills in The Book of Negroes, Păpucaru avoids generalizations without downplaying historical and/or personal tragedies. “Saint George to the Maiden: Wait in the Car” commemorates her sister on the day that “would have been your forty-third anniversary” and points out her father’s revolt against a death that might had been avoided:

Father’s fist breaks glass shower door. I take sister to neighbours.

Orthodox Jews. Won’t call an ambulance on the Sabbath.(“Saint George to the Maiden: Wait in the Car”)

A non-linear autobiography, The Panic Room meanders back and forth from the present moment, when the poet works as a costumer service representative for a toy factory, to distant childhood scenes; occasional teenage hook-ups; trips to Europe; her aging parents’ illness; a midlife birthday with her now-adult son; window shopping; being bullied by a stranger while jogging; and many others, relaying the whims of emotional memory. Her pilgrimage in time and space does not aim to retrieve her parents’ cultural roots, as in Magyarázni (Coach House Books 2016) by Helen Hajnoczky, another second generation-Canadian poet. Instead, Păpucaru actively lives with and through them. She calmly acknowledges herself as culturally hybrid and, in fact, cosmopolitan. Bucharest, London, Paris, and Toronto share the page of the same poem, “Wish You Were Here,” receiving equal emotional treatment, while numerous other places from numerous other countries loom throughout the book. The collection also alternates with ease between various genres, from more traditional, though still postmodern poems to lists, haiku, and prose. The amalgamation surprises and fends off emotional overload and stylistic saturation.

It was when I least expected it that the final suite of poems returned my hope in our species’ survival prospects. Raw, honest, and playful, they narrate a two-week road trip turned love affair and initiation ritual, presumably between the poet in her 20s and truck driver Didier. English mixes with French, in direct citations from their dialogues, while naturalistic details related to bodily functions and sex alternate with tender metaphors:

Une belle huitre, he’d say, hacking up phlegm.

A pretty oyster I’ve made. He taught me to hold

a champagne flute by the stem, to eat cheese

at room temperature only, to taste la mer

in a raw sea urchin.(“Game”)

Multiple-Choice Conclusions

- I fear the “muscle memory anesthetised.”

- I suspect in myself a lack of empathy.

- My group therapy facilitator ignores me if we accidentally meet anywhere else but at our meetings.

- All of the above.

If you can circle any these, Păpucaru’s meaningful and subtle debut collection might be the wake-up call you need. Despite the irony and self-irony, The Panic Room reasserts the cathartic value of reading and writing.

–

The Panic Room was longlisted for the 2018 Gerald Lampert Memorial Award.