The League is proud to run a variety of programs and services that support poets and poetry in Canada. Find out more about the various programs, events, and publications organized by the League of Canadian Poets below.

Programs

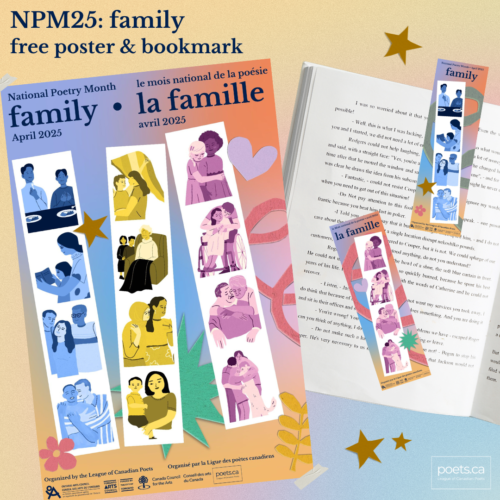

National Poetry Month | Le Mois national de la poésie

April is National Poetry Month!

Established in Canada in 1998 by the League of Canadian Poets, National Poetry Month takes place every April and brings together schools, publishers, booksellers, literary organizations, libraries, communities and poets from across the country to celebrate poetry and its vital place in Canada's culture.

Each year, the League of Canadian Poets selects a theme to ground our conversations, inspirations, and focus of National Poetry Month. LCP produces posters and bookmarks reflecting this theme, which are free to request for your home, school, library, or community!

L'avril c'est le Mois national de la poésie!

Établie au Canada en 1998, le MNP rassemble les écoles, les maisons d’éditions, les librairies, les bibliothèques, les organismes littéraires et les poètes de partout au Canada afin de célébrer la vitalité d’une poésie bien ancrée au sein de la culture canadienne.

Chaque année, la Ligue des poètes canadiens choisit une thématique pour faire converger nos conversations, et nos inspirations pendant tout le mois d’avril. Que ce soit pour vous, votre école, votre bibliothèque, ou votre communauté, le Mois national de la poésie vous enverra gratuitement, sur demande, des signets et des affiches reflétant notre thématique.

Copywell: Your Publishing Partner for National Poetry Month

The League is thrilled to announce a National Poetry Month 2025 partnership with Copywell to celebrate the timeless art of poetry. This collaboration exemplifies Copywell’s commitment to supporting authors, publishers, and creative communities in bringing their unique voices to life through beautifully crafted books. Copywell is providing the professional printing of NPM25 posters and bookmarks.

Poem in Your Pocket Day

Poem in Your Pocket Day is an international movement that encourages people to centre poetry within their daily interactions. Poem In Your Pocket Day is celebrated in the last week of National Poetry Month (April). On PIYP Day, select a poem, carry it with you, and share it with others at schools, bookstores, libraries, parks, workplaces, coffee shops, street corners, and on social media using the hashtag #PocketPoem.

The LCP also hosts an annual contest in Autumn to select the poems included the Poem In Your Pocket Postcard Collection.

La Journée du poème à porter

La Journée du poème à porter est un événement auquel toutes et tous peuvent participer en partageant leur amour de la poésie. Pour cette adaptation francophone de l’événement Poem in Your Pocket Day, qui se tient le dernier jeudi du mois d’avril, La poésie partout propose une sélection de textes de poètes du Québec, du Canada francophone et des Premières Nations. Tout le monde peut porter un poème, sans le dire à personne, ou bien en utilisant le mot-clic #poèmeàporter.

Depuis 2017, La poésie partout organise la Journée du poème à porter parmi ses multiples activités de diffusion et de dissémination de la poésie.

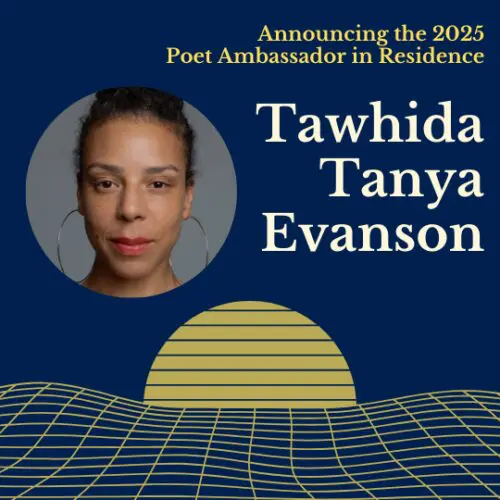

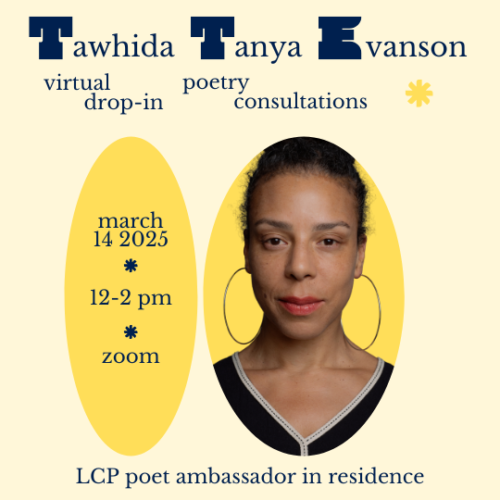

Poet Ambassador in Residence

The Poet Ambassador in Residence program is an opportunity for the League to work with some of Canada’s most exciting poets in support of our mission. In addition to receiving financial support for their own creative work, the Ambassador will work directly with the League’s community of poets through drop-in consultations, workshops, and events. The Ambassador will also support several of the League’s cherished core programs such as Poem in Your Pocket Day, the LCP Chapbook Series, and Poetry Pause.

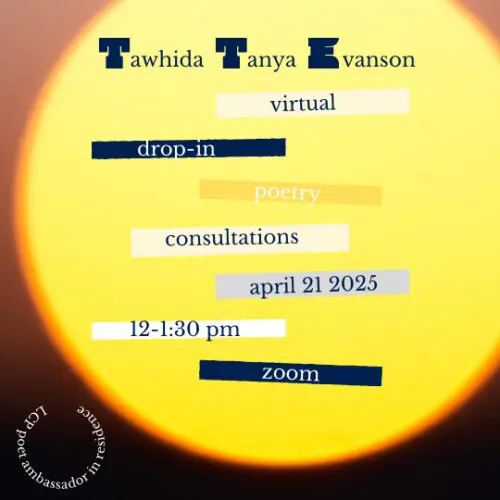

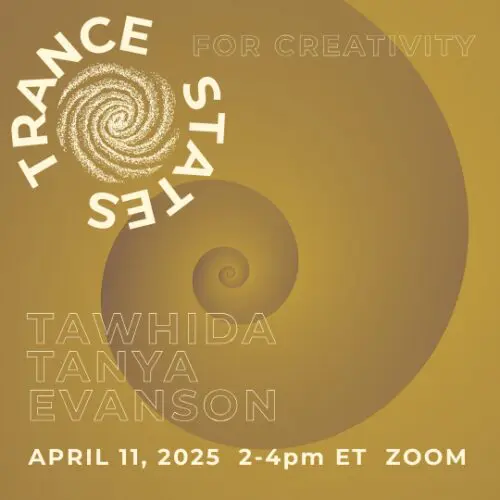

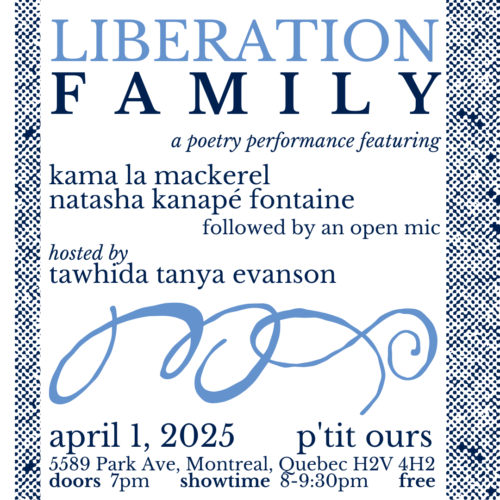

Poet Ambassador in Residence events

Book reviews

The League is proud to run a volunteer reviews program, which allows poets to be reviewed by their peers. The League maintains a database of reviewable titles, accessible via the link below.

To request a review copy: send an email to the email address listed in the reviewable titles database (this will differ by title).

To submit a review for publication: email your completed review to nicole@poets.ca.

To add a title to the database: complete the form via the link below.

Please note: the League does not accept unsolicited hard copies of books for review; books received by mail will not be added to the database.

In Conversation podcast series

Initiated by the Feminist Caucus, the In Conversation podcast series is a space for poets to come together and discuss the themes, issues, joys, and perils of being a poet in our time. You can listen to In Conversation episodes on Youtube.

Events

League event details and registration

The League uses a selection of different platforms for event registration. Most League events are hosted online on Zoom. Online events are not always recorded; when they are, participants will be made aware of this. Closed captioning is available at all online events.

At this time, the League does not maintain an events calendar; however, we often share information about events on Facebook and Instagram, as well as through our newsletter, Between the Lines. We cannot guarantee the distribution of any event details, but you may submit details on an upcoming event through this form.

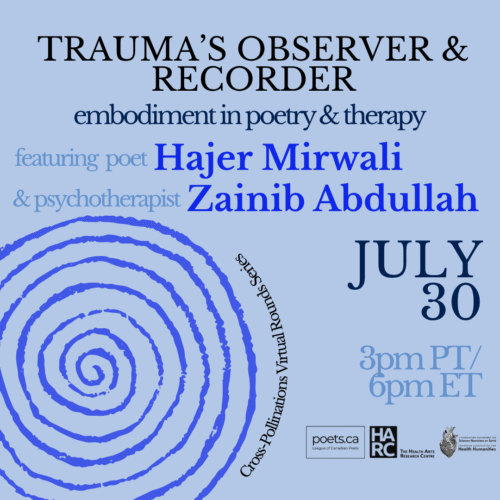

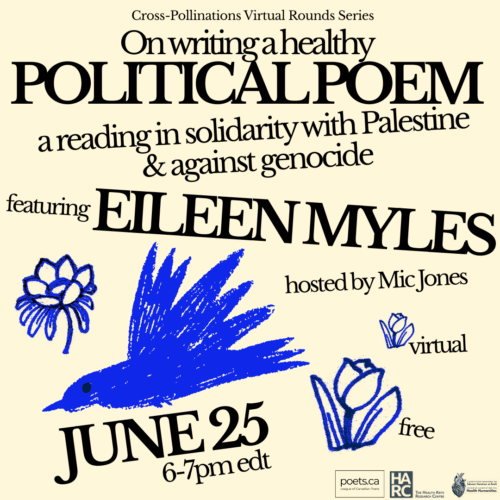

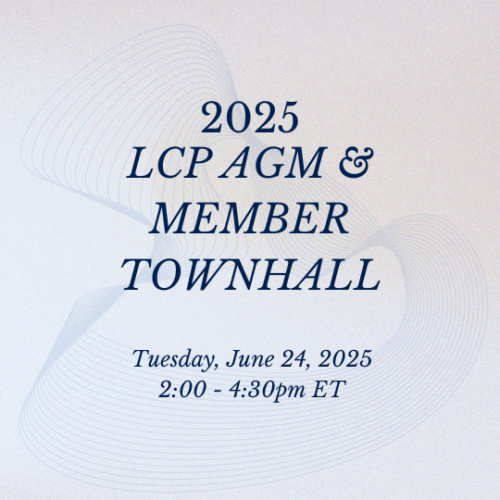

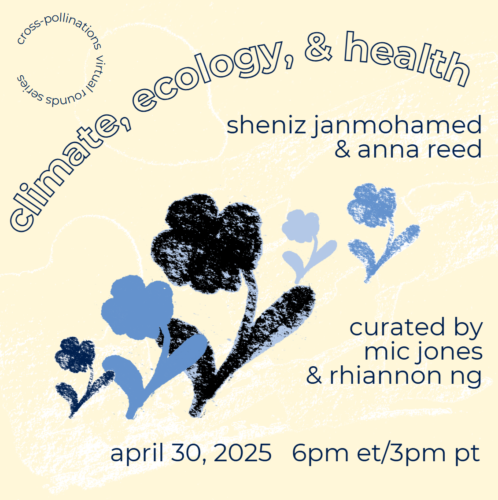

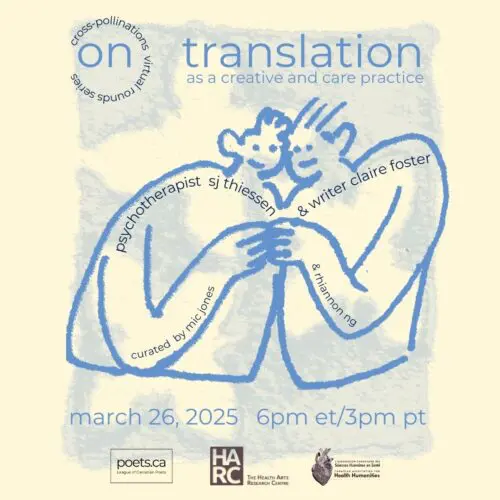

Cross-Pollinations Virtual Rounds Series

A partnership between the League, the Canadian Association for Health Humanities, and the Health Arts Research Centre.

In Cross-Pollinations, health humanities and poetry come together under the same scope, combining artistic expression with health practice and research. The conversations of Cross-Pollinations illuminate new and emerging insights and perspectives on healthcare opportunities and challenges, healthcare approaches and advances, as well as build bridges of connection between health professionals, humanities and the arts.

Events take place on Zoom, the last Wednesday of each month at 6pm ET/3pm PT.

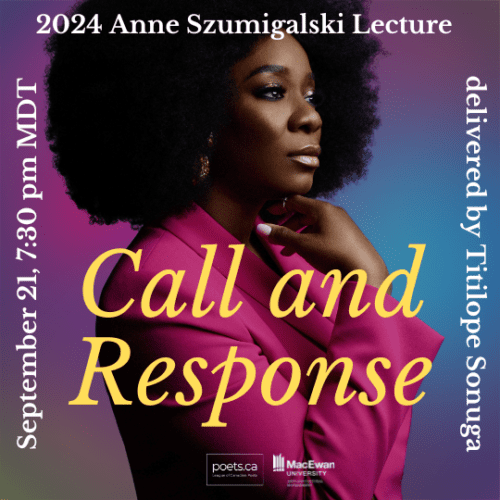

Anne Szumigalski Lecture Series

Established in 2002 and modeled after the Margaret Laurence lecture series, the Anne Szumigalski lecture series presents an annual lecture from a distinguished Canadian poet on craft, culture, and community.

Past lecturers have included Billy-Ray Belcourt, Louise Bernice Halfe-Sky Dancer, Tolu Oloruntoba, Alice Major, Lillian Allen, Anne Carson, and Dionne Brand, among others.

These lectures have ranged from deeply academic to profoundly creative, and have engaged questions of social justice, politics, and identity in their explorations of poetry.

Lectures are available to view on Youtube, or to read in the anthology Measures of Astonishment or in Prairie Fire magazine. Find links below, under past lectures.

Published in 2016 by the University of Regina Press, Measures of Astonishment anthologizes most of the lectures from the Anne Szumigalski Lecture Series's first two decades.

From the preface, by Glen Sorestad:

Anne Szumigalski claimed that as a very young girl she knew that she was going to be a poet, that it was to be her goal in life and indeed, that even at an early age she knew that she was a poet. By the time of her death in 1999, Anne Szumigalski was one of Canada’s most widely respected poets, a Governor General’s Award-winner, an active force in the Saskatchewan and Manitoba writing communities, a strong influence on and a tireless mentor for a great many writers. Her home in Saskatoon became literally a poetic drop-in centre. Szumigalski, as one of the founders of the Saskatchewan Writers’ Guild, was a strong champion of writing organizations and was also a long time member of the League of Canadian Poets. How fitting then that the League should choose to name after Anne Szumigalski its inaugural lecture series by Canadian poets about the art and craft of poetry by Canadian poets, the Anne Szumigalski Lecture Series. This was done as a lasting recognition of the stature that Szumigalski held as a poet among her colleagues across the country.

Though each of the lectures was initially given as an address to a poetry-friendly audience, the appeal and importance of the lectures is reflected in the fact that Prairie Fire, the excellent Winnipeg literary journal, quickly stepped in to ensure that the oral presentations would then find another audience, a literary reading audience. As well, the lectures also have been included on the website of the League of Canadian Poets, so they have been and are available to readers throughout the world. However, the idea of having the entire series to date appear in print in a single volume seems the logical next step towards giving these valuable insights and reflections the largest audience possible. Only one of the lectures does not appear in this volume: Dionne Brand was the second Szumigalski lecturer and apparently she gave her well received address from a series of note cards and never did write a complete address that could later be published.

Open mic nights and member readings

In the spirit of the Joseph Sherman New Member Reading, the League is proud to offer regular virtual events where members can read poetry and connect as a community!

These online events happen approximately once per month, and open mic spots are available to a different group of poets at each event (most often based on geography).

We encourage all poetry lovers to attend these events, but reader spots are typically reserved for League members.

Freedom to Read Week

Each February, the League joins writers, readers, libraries, schools, and publishers all across Canada in celebrating Freedom to Read Week. Since 2022, we have hosted a panel discussion featuring poets from communities whose voices and stories are often challenged and silenced.

BIPOC Writers Connect

BIPOC Writers Connect: Facilitating Mentorship, Creating Community is a virtual conference for Black, Indigenous, and racialized emerging writers to connect with industry professionals, established authors, and fellow emerging writers — all in one place! Presented by The Writers' Union of Canada (TWUC) and the League of Canadian Poets (LCP). TWUC and LCP are committed to cultivating space where BIPOC writers can share tools, strategies, feedback, and knowledge.

BIPOC Writers Connect includes:

- one-on-one time for feedback with a professional writer who has reviewed your work in advance;

- panel discussions with literary industry professionals;

- a behind-the-scenes look at manuscript selection as panelists offer feedback on the first pages of anonymously submitted manuscripts;

- workshop on writing query letters; and

- networking opportunities.

Event recordings

Many of the League events are recorded and available through our Youtube channel. If you are seeking a particular recording and you aren't able to find a video on our Youtube channel, please contact info@poets.ca.

None of the League's open mic events are recorded.

Recordings from member-only events are available to members only.

Publications

Poetry Pause

LCP Chapbook Series

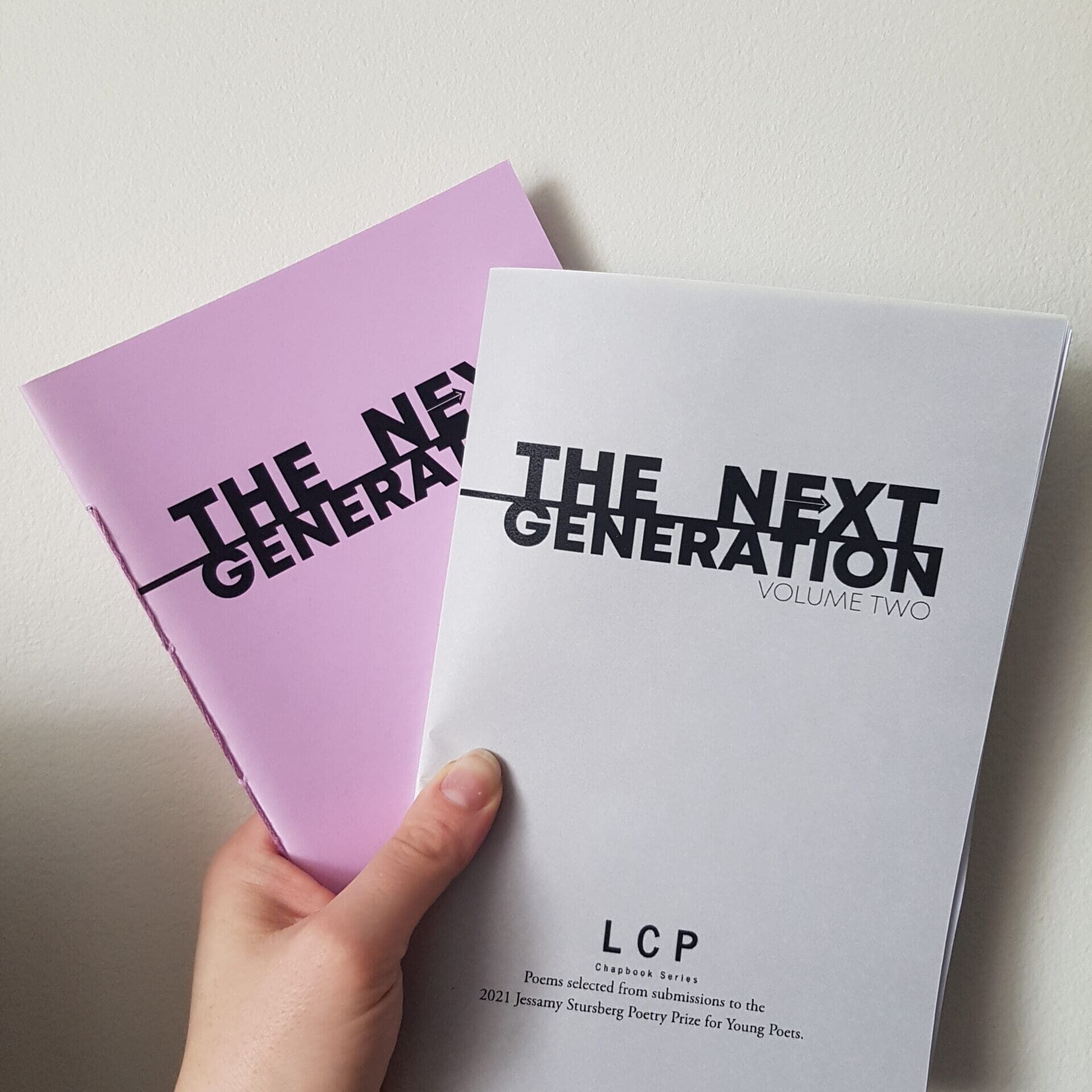

The Next Generation: Vol. V

Celebrate the winners of the 2024 Jessamy Stursberg Poetry Prize for Young Poets in the fifth edition of The Next Generation, a chapbook of poems by youth.

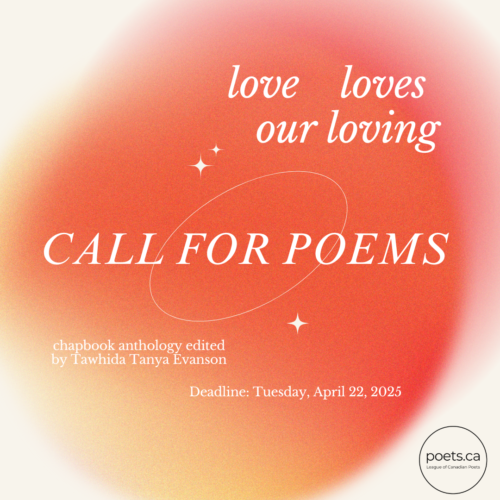

Call for submissions: Love Loves Our Loving

The League invites submissions of poetry that reflect the theme “Love Loves Our Loving” for publication in a forthcoming chapbook, edited by Tawhida Tanya Evanson.

Of our own making

Edited by Tara Borin, this chapbook anthology features poetry from: Terrence Abrahams, Jenna Lyn Albert, Alexa Boismier, Ellen Chang-Richardson, Conyer Clayton, Benjamin C. Dugdale, Neven Marelj, Drew McEwan, Khashayar “Kess” Mohammadi, Helen Robertson, Harper Walton, Jennifer Wenn, and Ash Winters.

Splendor of Wings

Edited by Claudia Coutu Radmore, this chapbook anthology features poetry from: Anne Archer, Marilyn Belak, Richard Brait, Michelle Poirier Brown, Ronnie R. Brown, Neall Calvert, Louise Carson, Eric Folsom, Tom Gannon Hamilton, Eva Kolacz, Janis La Couvee, Donna Langevin, Dorothy Mahoney, Blaine Marchand, Shelley McAneeley, Gil McElroy, John Oughton, Kerry Rawlinson, and Nan Williamson.

The Next Generation volume 4

Vivian Sun, Zixuan Xu, Sana Huang, Meala Sang, Caoimhe Karl, Jaiden Ahuja, Leonardo Yang, Sofia Varma-Vitug, Emily Lane, Vanessa Chen, Asma Ameen Majeed

Adventitious Sounds

Candace de Taeye, Ivy Deavy, Annie Foreman-Mackey, Kaylie, Kathleen Klassen, Madeline McKenzie, Lori-Anne Noyahr, Savita Rani, Eleonore Schönmaier, Lauren Seal, Kimberley Thomas, James X. Wang, Laura Zacharin.

Spectral Lines Visual Poetry Chapbook

Christian Bok, Moni Brar, Benjamin C. Dugdale, Sarah Imrisek, Daze Jefferies, Samantha Jones, Eimear Laffan, Mark Laliberte, Carol MacKay, Colin Morton, Cassandra Myers, katie o’brien, Nikki Reimer, Rasiqra Revulva, Dani Spinosa, Kate Sutherland, Grant Wilkins

The Next Generation: Volume 3

Briana Lu, Grace Hu, Maggie Yang, Kyo Lee, Angel Zhao, Sofia Varma-Vitug, Eryn McNamara, Gurleena Sukhija, Samuel Nnadi, Avery E. Kats, Ria Baxi, Angela Cen, Sarah Ng, Catie Musselman, Alison Wang, Sana Huang

On the Storm / In the Struggle: poets on survival

Donald B Campbell, Sam Cheuk, Audrey Lane Cockett, Bashar Lulu Jabbour, Kyla Jamieson, Penn Kemp, Vivian Li, Willow Loveday Little, S.A. McCormick, Sorouja Moll, Richard-Yves Sitoski, Myna Wallin, Erin Wilson, Heather J. Wood and Anna Yin.

AHVAZ // AAVAZ // AVAAZ

Manahil Bandukwala, Gavin Barrett, Farah Ghafoor, Meharoona Ghani, Maryam Gowralli, Laboni Islam, Saakshi Patel, Ayaz Pirani, Fauzia Rafique, Renee Sarojini Saklikar, Amritpal Singh Arora, Sanna Wani

The Compassionate Poet: An exploration

Grace Lau, Phoebe Wang, Renée Sarojini Saklikar, Heather Birrell, Tara Borin, Molly Cross-Blanchard, Margo LaPierre

(SOLD OUT) Leap

Anne Archer, Sonja Arntzen, Barbara Black, Carol Casey, H.E. Casson, Marlene Grand Maître, Carla Harris, Louisa Howerow, Norma Kerby, Sharon Lax, Josephine LoRe, Jane Macdonald, Dharmpal Mahendra Jain, Tanya McIntyre, Anita Ngai, Susan Publicover, Carol A. Stephen and Susan Wismer.

(SOLD OUT) the way out is the way in

Sophia N Ashley, Roxanna Bennett, Ashley-Elizabeth Best, Virginia Boudreau, Anna Cavouras, Leanne Charette, Sile Englert, Victor Enns, Meharoona Ghani, Amy LeBlanc, Valerie Losell, Katie MacLean, Margarita Papenbrock, Kelly S Thompson, nancy viva davis halifax

The Next Generation volume 2

Angela Cen, Vanessa Chan, Izabella Salih, Mark Kim, Michelle Masood, Nida Atique

You are a Flower Growing off the Side of a Cliff

Volume one: Jessica Coles, Lorne Daniel, griffin epstein, Clara A. B. Joseph, Dan MacIsaac, Kate Marshall Flaherty, Antigone Oreopoulos, Julia Sorensen, Andrea Thompson and Erin Wilson.

Volume two: Moni Brar, Franco Cortese, Catherine Grahame, Samantha Jones, Karen Klassen, Kelly B. Madden, Kim Mannix, Anna Quon, Greg Santos, Lauren Seal, Catherine St. Denis, Amy Willans, and Anna Yin.

Voices of Quebec | Les voix du Québec

Mia Anderson, Martine Audet, Sarah Burgoyne, Louise Carson, Flavia Cosma, Liana Cusmano, Julie de Belle, Denise Desautels, Antony di Nardo, Louise Dupre, Nancy R. Lange, Jeff Parent, Diane Regimbald, Cora Sire, Derek Webster

The Next Generation volume 1

Kate O’Connor, Nazanin Soghrati, Kira Belaousoff, Crystal Peng, Max Schlodder, Zara Zafar

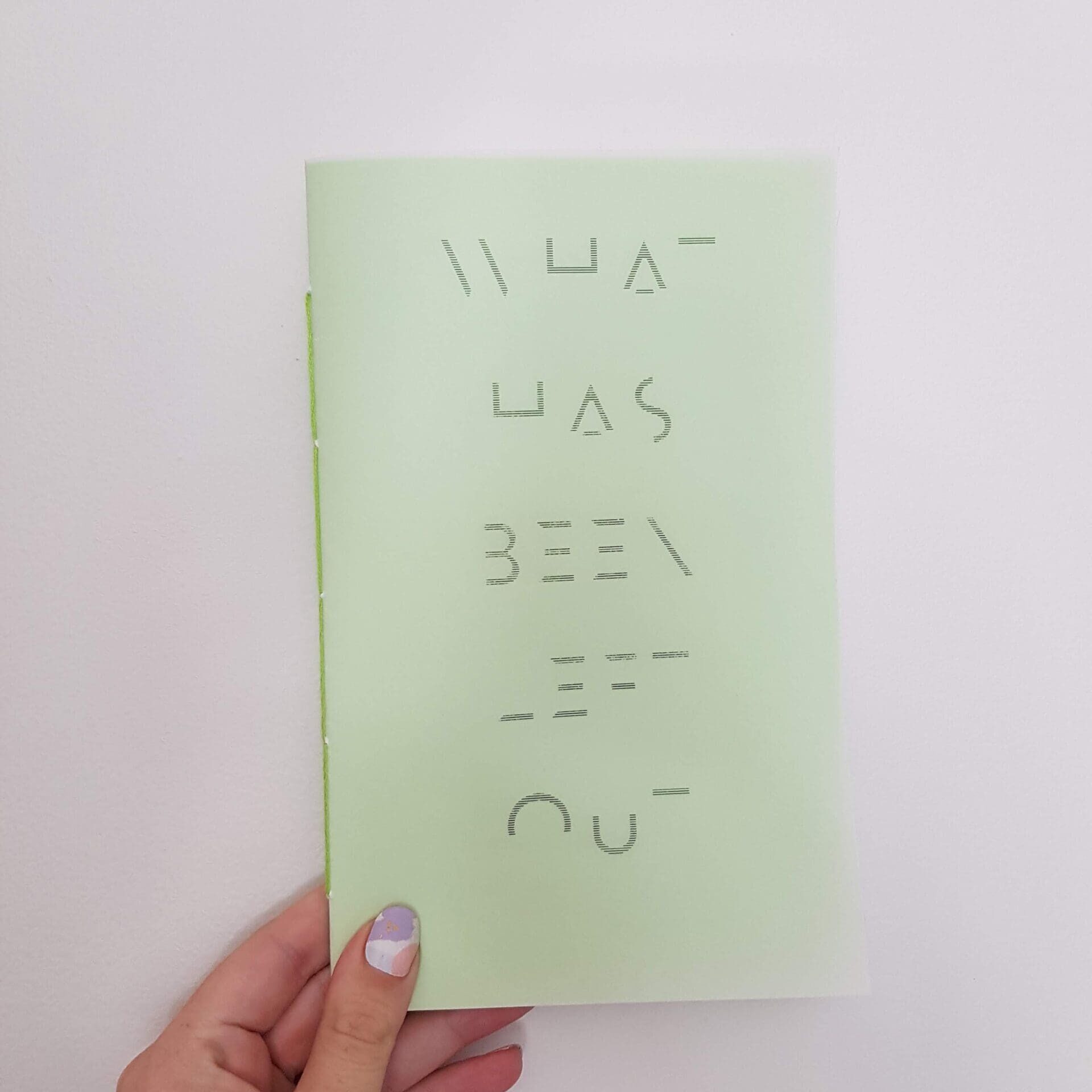

What has been left out: Feminist Caucus Living Archive Series

Ayesha Chatterjee, Shazia Hafiz Ramji, Joanne Arnott, Sadiqa de Meijer, Jónína Kirton, Valerie Mason-John, Andrea Thompson, Ayesha Chatterjee, Shazia Hafiz Ramji, Joanne Arnott, Sadiqa de Meijer

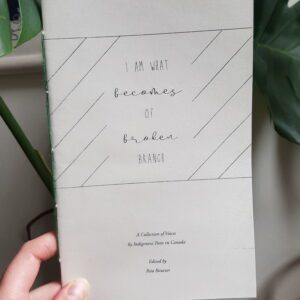

I am what becomes of broken branch

Michelle Brown, Kirk Bueckert, Carol Casey, Colleen Charlette, and Cooper Skjeie

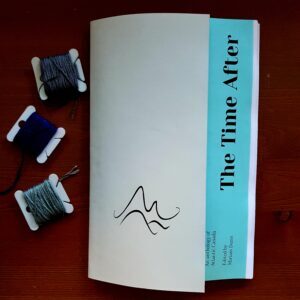

The Time After: poetry from Atlantic Canada

Donna Allard, Janet Barkhouse, Jeri Brown, Lucas Crawford, Alison Dyer, John Flood, Kayla Geitzler, Jennifer Houle, Matthew Gwathmey, Kathy Mac, Tiffany Morris, Michelle Porter, Anna Quon, Eleonore Schönmaier and Elizabet Stevens

(SOLD OUT) Fresh Voices: Tending the Fire

Susan J. Atkinson, Michelle Poirier Brown, Carol Casey, Ellen Chang-Richardson, Shayne Coffin, Pat Connors, Sarah Hilton, Louisa Howerow, Norma Kerby, Shannon Kernaghan, Chloe Lewis, Kelly B. Madden, Laura McGavin, Natasha Ramoutar, Archana Sridhar and David Yerex Williamson.

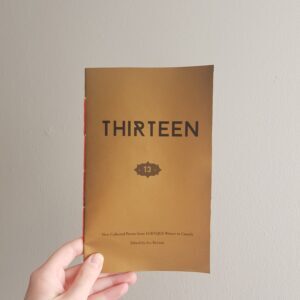

Thirteen: New Collected Poems from LGBTQI2S Writers in Canada

John Barton, Karin Cope, Tanis Franco, Keith Garebian, Kayla Geitzler, matthew heinz, Rachel Lallouz, Chloe Lewis, Nisa Malli, Trish Salah, Jane Shi, Matthew Stepanic, John Emil Vincent

These Lands: a collection of voices by Black poets in Canada

Fiona Raye Clarke, Catherine Esther Cowie, Irene Moore Davis, Trynne Delaney, Marita Forget, Shery Alexander Heinis, Charlotte Henay, Alannah Johnson, Victoria Mbabazi, Emmanuel Uweru Okoh, stephanie roberts and Blossom Thom

Collected Haiku

Maxianne Berger, Barbara Black, Nane Couzier, Anne Dunnett, Rhonda Ganz, Dorothy Mahoney, kjmunro, Ulrike Narwani, Marianne Paul, Jacquie Pearce, Pauline Sameshima, Beth Skala, Richard Stevenson, George Swede, Sarah Wiseman and Derk Wynand.

Fresh Voices

Fresh Voices was created by Associate Member Lesley Strutt to showcase the great work being produced by the League’s associate members. Prior to 2024, issues were published three times per year. In May 2024, the Fresh Voices program shifted to a weekly publication format, with one poem featured each Friday in Poetry Pause. Browse past issues and individual poems below.

This opportunity is open only to Associate members of the League. Not yet a member? Please visit our membership page for details on how to apply!